March 23, 2017

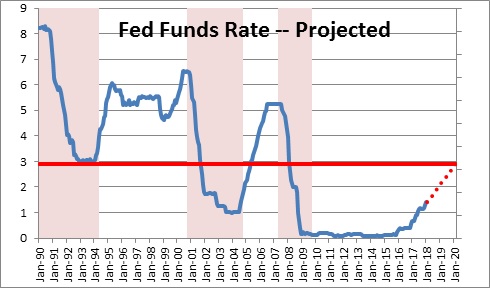

At the first FOMC gathering with Jerome Powell as Fed Chair, he and his colleagues on the FOMC incorporated tax cuts into its forecast for the first time. The Fed believes that the cuts will boost GDP growth in 2018 and 2019 but will have little impact thereafter. Its expectation for inflation was essentially unchanged at 2.1%. Against this backdrop, the Fed indicated a willingness to boost the funds rate to 3.4% in 2020 which is 0.3% higher than it suggested three months ago. Why is this important? Because the Fed believes its policy is neutral when the funds rate is 2.9%. Thus, it is suggesting that by 2020 it will venture into “tightening” mode for the first time in 13 years. In the past when it boosted interest rates it could claim that it was not “tightening” but simply lifting the funds rate towards a more neutral policy stance. By 2020 that will no longer be the case.

With respect to GDP growth, the Fed believes the tax cuts will stimulate GDP growth to 2.7% and 2.4% in 2018 and 2019, respectively. Those forecasts are 0.2% and 0.3% higher than it thought previously. However, the Fed does not believe there will be any long-term impact from the tax cuts. By 2020 it suggests that GDP growth will revert to a 2.0% pace which is exactly what it anticipated back in December. The Fed continues to believe that potential GDP growth will be steady at 1.8%.

Thus, the Fed does not believe that the corporate tax cuts will boost the economy’s potential growth pace. That is the primary difference between its forecast and our own. We highlight the fact that the tax cuts boosted the pace of investment spending in 2017, and we expect faster growth in investment to continue through 2020. In the process productivity growth will quicken from 1.0% to 2.0%, which will thereby raise the economy’s potential GDP growth rate from 1.8% to 2.8%. It is an important difference. If that happens, the economy can grow more quickly without triggering a pickup in inflation, which means that the Fed has no need to boost the funds rate above the neutral level. At this point nobody knows which view might be more correct but as time passes and more data are collected the difference will be resolved.

The Fed did not appreciably alter its forecast for inflation. It suggests that the core CPI (i.e., excluding the volatile food and energy components) will be 2.1% in both 2019 and 2020. Previously it had both growth rates pegged at the 2.0% mark.

Given that the economy is at full employment, how can it envision faster GDP growth without any significant pickup in the pace of inflation? Presumably it believes that higher interest rates will be required to prevent the inflation rate from accelerating. In December it expected the funds rate in 2020 to be 3.1%. Today it believes it will likely be 3.4%. While that is only 0.3% higher than its earlier prediction, it is 0.5% higher than the 2.9% level that it believes is a “neutral” rate. What this means is that by 2020 the Fed will shift into “tightening” mode for the first time since 2007. It is easy to raise the funds rate when it is far below its so-called “neutral” level. There is no real risk of overdoing it and possibly sending the economy into a tailspin. But once it starts raising rates above that neutral level, the danger of going too far and inadvertently triggering a recession increase considerably. It is a time when the Fed, and all of us, need to start paying close attention to the incoming data.

Will 2020 mark the end of the road for the expansion? No. In 2007 the Fed had to boost the funds to the 5.25% mark before the economy slipped over the edge into recession. As we see it two things are important. First, 2020 is two years down the road and everybody’s forecast will change in the interim. Second a funds rate of 3.4% is not 5.25%. The funds rate will probably not yet be at a danger point. But if the Fed is willing to venture into “tightening” mode, the end of the expansion is getting closer. Once that happens it is telling the world that it wants to slow the pace of economic activity. That shift in attitude rarely has a happy ending.

Stephen D. Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me