June 14, 2024

Once a quarter the Federal Reserve updates its forecasts for GDP growth, inflation, and interest rates for the next couple of years. Economists agonize over the significance of the Fed’s latest forecasts relative to what it thought three months earlier. This past week we learned that Fed officials expect one or perhaps two rate reductions by yearend, followed by an additional four rate cuts in 2025. In March it had anticipated four rate cuts this year. The interpretation is that the Fed has suddenly become more hawkish. Nonsense. The Fed’s outlook for the rest of the year changed because inflation actually edged higher during that three-month period rather than continuing its gradual descent. Furthermore, while the Fed anticipated fewer rate cuts in 2024 it added an additional rate reduction in 2025 and the funds rate at the end of that year is little different from what it was earlier. That is hardly indicative of a tighter policy stance. The Fed simply delayed the initial rate cut because the economic environment changed. Our guess is that every private sector economist’s outlook changed by a roughly comparable amount. And let’s be serious. The dot plot diagram developed in mid-June anticipates a rate cut in November at the earliest. That is five months hence. Every economist’s outlook is going to change between now and then as incoming data are received. The Fed’s current outlook seems reasonable to us, but it is a forecast not the gospel.

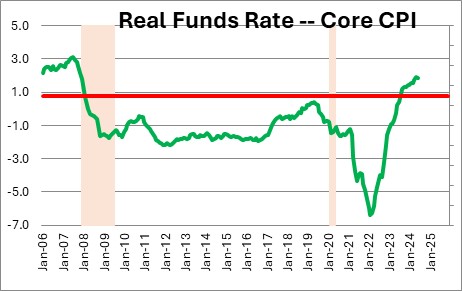

We should not use the nominal funds rate to determine the tightness of Fed policy. A 10% funds rate might seem high. but if inflation is also 10% Fed policy is not tight at all. Rather, economists should look at the funds rate in inflation-adjusted or “real” terms. Today the funds rate is 5.3%. The core CPI is 3.4%. Doing the subtraction, the real funds rate currently is +1.9%. It is clearly higher than it has been since 2007. But is it “too high”? The Fed believes that in equilibrium — when the inflation rate is 2.0% — the funds rate should be 2.8%. Thus, the real funds rate in equilibrium should be +0.8%. But inflation today is not 2.0%, it is 3.4%. Fed policy should be in restrictive mode. With the real funds rate currently at +1.9% and neutral at +0.8%, Fed policy does not appear overly restrictive which means there is little danger of inadvertently dumping the economy into recession.

Having said that, we are beginning to see (at long last) some softening in the labor market, home sales are struggling as mortgage rates hover around the 7.0% mark, and consumer spending is finally beginning to moderate. All of those are positive developments. In the past four quarters GDP growth has averaged 2.9%. Potential growth is 2.0%. The economy needs to slow a bit to help bring down the inflation rate. It does not need to dip into recession. A slowdown to the 2.0% mark would be welcome, which happens to be our GDP forecast for the second half of this year.

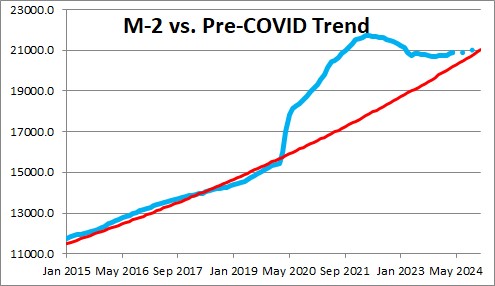

The other part of the equation that will determine the proper course for Fed policy is the inflation rate. We continue to believe that the problem with the inflation rate is that the Fed flooded the economy with liquidity when it purchased trillions of dollars of government and mortgage-back securities between March 2020 and March 2022 and money supply growth soared. Because the Fed mistakenly believed that the run-up in inflation would be temporary, it was slow in adjusting its policy stance and the faster inflation rate became firmly entrenched. However, the Fed began to shrink its portfolio in July 2022 and it has eliminated much of the surplus liquidity. We estimate that currently about $0.7 trillion of surplus liquidity remains. If the Fed continues to shrink its portfolio the remaining surplus liquidity should be eliminated by year end. That should pave the way for a further slowdown in the inflation rate from 3.4% currently to the 2.0% target.

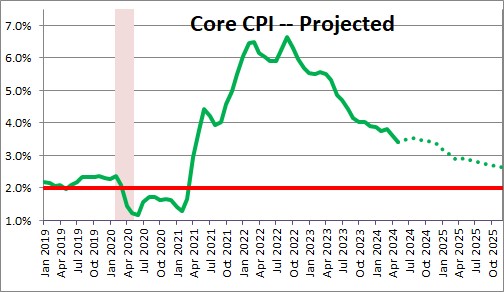

Having said that, there is likely to be little further reduction in the inflation rate between now and yearend. The reason is simply a matter of math, not economics. When we talk about the inflation rate we talk about the year-over-year growth rate. For any given month we already know what happened in the previous 11 months, so whether the year-over-year growth rate accelerates or slows depends on the change in the inflation rate for the current month compared to its change in the comparable month of the prior year. For example, the year-over-year CPI currently is 3.4%. We expect the core CPI to rise 0.3% in June. But in June of 2023 the core CPI rose 0.2%, As a result, when we see the CPI for June we should find that the year-over-year growth rate accelerates by 0.1% from 3.4% to 3.5%. Unfortunately, between June and December 2023 the average monthly increase in the core CPI was 0.27%. To show any slowdown between now and the end of this year the monthly gains will have to average something less than that. Could happen, but it seems to be a reach. As a result, we expect the core CPI to remain at 3.4% by the end of this year. The outsized gains in the first few months of this year mean that the year-over-year increase should begin to slow quickly in the first half of 2025 — dipping to the 2.9% mark by March. That should, in turn, pave the way for steady rate declines as that year progresses.

While we happen to think that the Fed’s outlook for GDP growth, inflation, and the funds rate are reasonable, we do not want to get too hung up on the so-called “dot plots”. The Fed does not know any more about the future than the rest of us. Its view – and ours – will be altered by the flow of incoming data. Furthermore, we have a presidential election on November 5 which could cloud the economic outlook for 2025 and beyond. The Fed does not expect rates rate to begin falling until late in the year which is five months away. In the economics world five months is a lifetime. So far so good, but stay tuned.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me