August 24, 2018

George Will recently wrote a column entitled “Another Epic Economic Collapse is Coming.” He notes that the stock market rally is now the longest-lasting bull market ever, that all economic expansions inevitably come to an end, and that no one saw the last one coming. What is bothering Will is the magnitude of the budget deficit and the fact that the ratio of debt to GDP will soon reach 100%. While we share his concern longer term we believe the headline is grossly inflammatory. This expansion, like all others before it, will eventually come to an end. But it will not die because of the rising level of government debt. It will end, like all its predecessors, because the Fed eventually tightens too much, raises interest rates too sharply, and the economy slips over the edge into recession. Debt may eventually become an issue, but the danger point is well into the future and may never materialize if future politicians choose to rein in government spending.

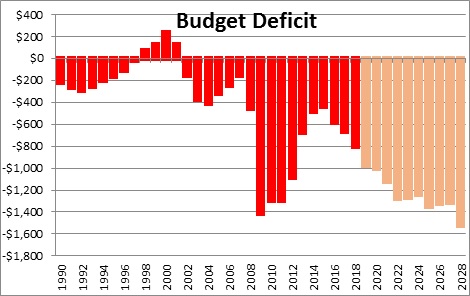

The Congressional Budget Office currently projects a budget deficit for fiscal 2019 of $1.1 trillion which gradually climbs to $1.5 trillion within a decade. At some point in that 10-year time horizon the expansion will end. Nobody knows exactly when. Most economists peg it for 2020. We would argue that the Fed will not raise short-term interest rates to a level that could endanger the expansion until several years later. But once the expansion ends tax receipts decline, entitlements like Medicaid and unemployment benefits rise, and the budget deficit will soar.

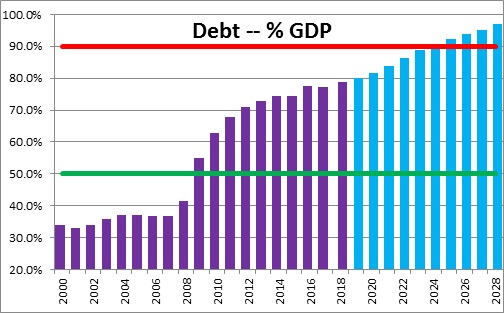

Because each year the Treasury must issue an equivalent amount of debt to finance the budget shortfall, debt as a percentage of GDP currently is projected to climb from 77% of GDP today to 96% of GDP by 2028. When the expansion ends and budget deficits soar, the debt to GDP ratio will climb and a more realistic estimate is a number in excess of 100%. The question is, at what point does the steadily eroding fiscal position of the U.S. become a problem?

Economists generally believe that a “sustainable” level of debt is something around 50% of GDP. When it climbs to the 90% mark foreign investors presumably get nervous and become less willing to hold that country’s debt. Once that happens interest rates must rise to attract the funds required to finance that level of debt. But 90% is not some sort of magic number.

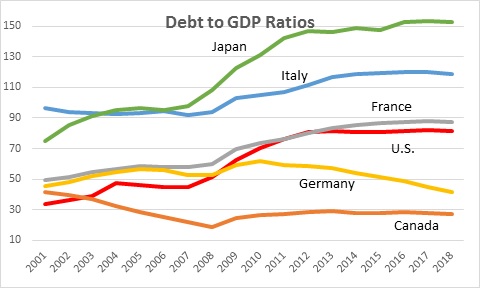

With that in mind, it might be useful to look at debt to GDP ratios for other developed countries. The U.S.is currently in the middle of the pack. Canada (at 27%) and Germany (at 42%) are doing a fine job of keeping their debt/GDP ratios below the desired 50% threshold. France at 87% is somewhat higher than the U.S. but, thus far, investors do not seem in the least bit concerned. Italy at 120% of GDP is beginning to get some pushback from investors. But Italy has been at that level for the past five years with few if any adverse consequences. Only now are investors becoming anxious.

Then there is Japan. It has had a debt/GDP ratio of 150% for the past seven years. Despite fears of an impending fiscal Armageddon, Japan seems to have had no difficulty financing its debt. But Japan is a unique case. The household savings rate in Japan is about 20% compared to 5% for the U.S. Thus, most of its government debt is held by Japanese investors. It need not worry about foreign investors getting nervous and suddenly deciding to dump their holdings of yen-denominated debt. Traders have been betting on a Japanese debt crisis for years and have been repeatedly frustrated.

Given Japan’s unique circumstances with its extraordinarily high savings rate it is probably not advisable for any other country to attempt to carry such a high level of debt. Italy at 120% may represent a more realistic upper limit. With the U.S. and France close to the 90% mark and neither country having any difficulty financing its debt, it seems likely that the 90% threshold is too low and that economists may be overly concerned.

Having said that, the debt to GDP ratio for all these other countries is projected to decline over the next decade. The U.S. is the only country where it is almost certain to rise even in the absence of a recession. Nobody knows what that magic number is, whether it is 90% or something higher. But only a fool would suggest that debt doesn’t matter, and the U.S. is on the wrong track. Right now, relatively small changes in policy can restore fiscal responsibility. The problem is that our policy makers in Washington – all of them on both sides of the aisle –are totally incapable of restraining government spending.

George Will has a point about budget deficits and debt. But it is a longer-term issue and not something that will bring the current expansion to an end. Rest easy for now.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

What an outstanding analaysis! Brilliant rebuttal against Mr Will’s click bait.

Mr. Slifer, May I ask where do you generally collect your data from? Especially these charts and graphs you made.

Thanks, Ray

Fear-mongering about the debt has been going on with gusto since the early 1980s. Yet we continue to run the deficits, interest rates on US debt stay low, and the US economy bustles. Why? First, the US issues debt in its own currency, second the dollar economy is much larger than the US economy, and people overseas will always take dollars in return for their goods and will always find things in the US that they want to buy… like real estate, college educations for their young people. The debt, to the extent that it is held by foreigners, is also largely a reflection of our trade deficit. Our dollars support rising living standards abroad. These dollars come back in part as Treasury purchases.

The data I use come from a variety of places. For example, the data on debt/GDP come from the IMF. Most sources I use are from the Census Bureau, Commerce Department, Labor Department, Energy Department, etc.

Hi Kerry,

Your comments are certainly accurate. We have been worrying about this issue for years and nothing bad has happened. But I still believe that at some point it will become an issue. Your are right that foreign investors need dollars and will continue to buy them. But if our debt keeps climbing and they get nervous and respond by simply buying fewer dollars and perhaps more Euros of yen, it will push rates higher. I do not think the U.S. is immune to the problem, but neither I nor anybody else can predict exactly where that danger point lies.

Steve