December 20, 2019

Throughout 2019 the fear was that slow growth overseas and a weak manufacturing sector could spread and pull the entire economy into recession. The Fed was so nervous it cut rates three times in an effort to prevent that outcome. The outlook for 2020 will be the opposite. In early December the employment report for November was surprisingly robust and confirmed that the economy is still on solid ground. Trump and the Congress reached an agreement on a revised NAFTA accord which will be ratified early next year. The U.S. and China reached a trade agreement which not only removes the fear of any further escalation of the trade war, but will also boost exports growth in both countries. The White House and Congress reached an agreement on government spending for 2020 which eliminates the possibility of a government shutdown at the end of this year. The Fed told us it intends to leave rates unchanged through the end of 2020. And Boris Johnson was re-elected in a landslide which means the Brexit uncertainty will be eliminated by the end of 2020. In the wake of all that news the stock market has soared to a record high level. All of the factors that weighed on GDP growth in 2019 will stimulate the expansion next year.

For 2020 we expect:

- GDP growth of 2.4%.

- Inflation to edge upwards to 2.7%

- The Fed will leave the funds rate unchanged in a range from 1.5-1.75%.

- The stock market will continue to climb to 3,500.

- Investment spending will rebound and raise the economy’s speed limit to 2.5%.

- The end of the expansion is not yet in sight.

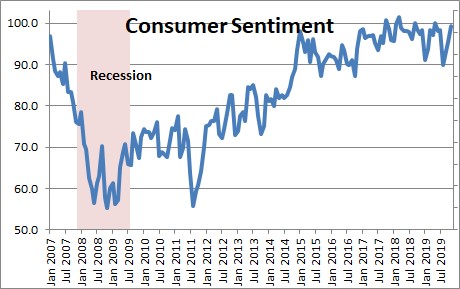

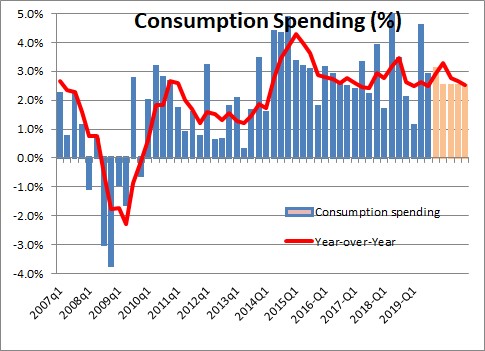

To get a handle on GDP growth for next year the place to start is consumer spending which represents two-thirds of the GDP pie. Sentiment is already high and may climb to a high for the cycle in the early part of 2020 given the developments described above.

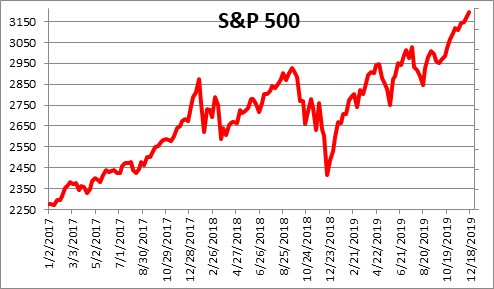

The consumer’s optimism seems well-justified. The stock market has surged in recent months to a series of record high levels. That not only lifts consumer spirits it bolsters their net worth.

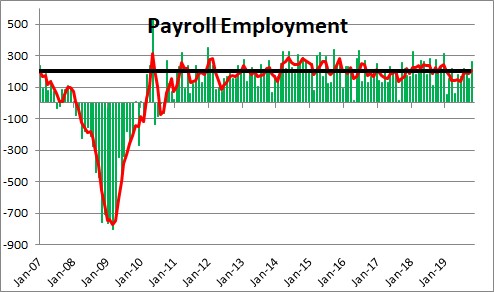

At the same time jobs growth has continued to defy expectations and averaged 185 thousand per month for the past year. At the same time the labor force has risen 130 thousand per month. Each month 130 thousand people per month want jobs, 185 thousand find them. The Fed believes that the economy is at full-employment when the unemployment rate is 4.1%. But is it? If the unemployment falls below that full-employment threshold, inflation should climb as employers pay higher wages to get the requisite number of employees. But even with the unemployment rate at 3.5% there is no sign of any meaningful upswing in inflation. Could full employment be as low as 3.5%?

Steady jobs growth and higher wages boost income. Confidence is soaring. Consumer debt in relation to income is extremely low. Interest rates are very low and should stay there for the foreseeable future. Given this backdrop we expect consumer spending to rise 2.5% in 2020.

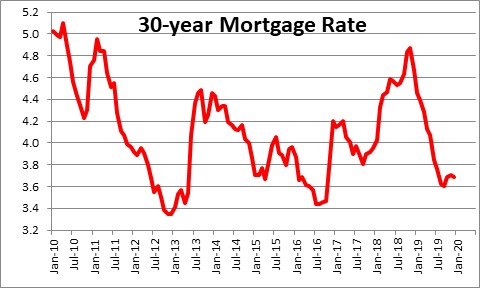

Fueled by near-record low 30-year mortgage rates of 3.7% the housing market is on fire and home sales have responded accordingly.

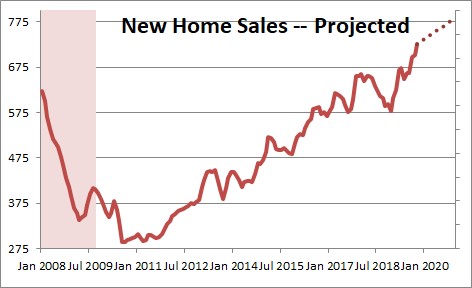

New home sales have risen 32% in the past year to 733 thousand which is the highest level since July 2007. Home sales would be even faster if there were more homes available for sale. Meanwhile builders’ confidence has surged to a 30-year high, but their output of new homes is being constrained by a shortage of qualified workers, an inadequate supply of available lots on which to build, and sharp increases in charges levied by local authorities.

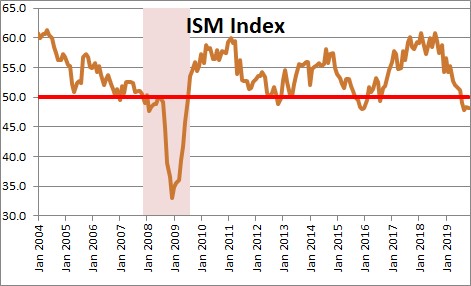

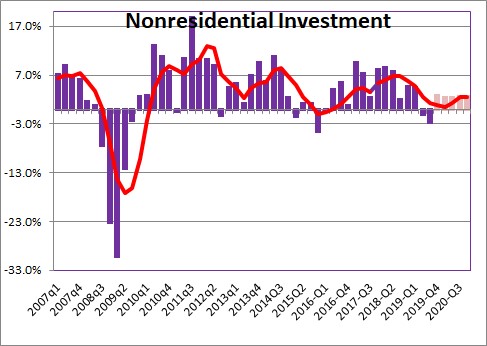

Investment spending, another 15% piece of the GDP pie, slowed sharply in 2018 as Trump’s inconsistent trade policy took its toll, particularly on the manufacturing sector which went into a yearlong slump. Business leaders are unwilling to build new plants and spend money on equipment in an environment where trade policy could shift at any moment. But the revised trade pacts with Canada and Mexico, and the trade agreement with China should lift the spirits of business leaders, particularly those in the manufacturing sector. We expect the purchasing managers’ index in 2020 to recapture much of the ground it lost in 2019.

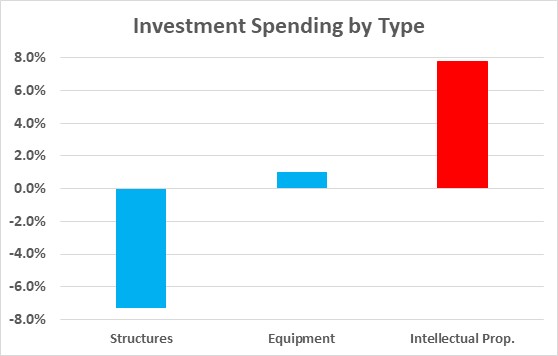

The other thing to keep in mind with respect to investment spending is that while construction of new factories declined sharply this year, and equipment spending changed very little, expenditures on computer equipment and software soared by about 8.0%. Presumably, this has been caused by tightness in the labor market. If firms cannot find an adequate supply of workers it makes sense to spend money on technology to make their existing employees more productive. They can thereby boost output without increasing headcount. That type of investment spending is also sure to pay dividends in the form of faster growth in productivity.

For this reason we do not want to be too pessimistic about the outlook for investment spending in 2020. Growth may not match the 7.0% pace achieved in 2017, but given the likely spending on technology in the quarters ahead we would suggest that a 3.0% rate of investment spending is easily achievable. If business confidence improves with the recently announced trade deals, investment spending could exceed the 3.0% mark.

The trade component of GDP is a mere 10% of the pie, but an important one because trade news spreads like wildfire. Its psychological impact on business confidence is probably more important that its actual impact on exports and imports. This past year the haphazard manner in which tariffs were imposed by President Trump created considerable angst amongst business leaders. However, after growing rapidly in 2018, both exports and imports were little changed for the year. As a result, the trade component of GDP was virtually unaffected. In 2020 we expect faster growth in both exports and imports and, once again, the trade component should have little impact on GDP growth.

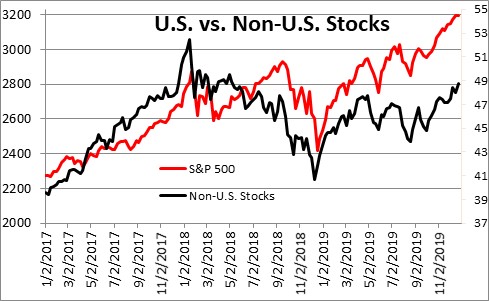

With respect to trade, it is important to note that the IMF expects global GDP growth to climb from 3.0% this year to 3.4% in 2020 with a modest pickup in Europe and more pronounced gains in Latin America and emerging countries. We suspect that the IMF is on the right track. While the S&P 500 index in the U.S. has risen 29% in the past year, stock markets outside of the U.S have climbed an impressive 14%.

Putting together these various GDP components, we come up with an estimate for GDP growth in 2020 of 2.4%. The consensus appears to be for GDP growth of about 2.0%.

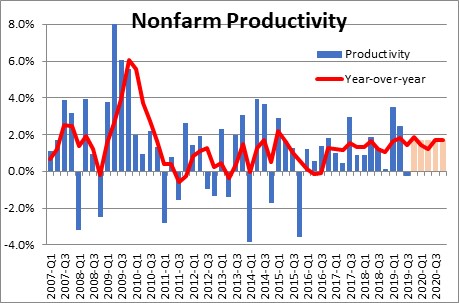

The real question is whether a growth rate of that magnitude can be sustained. We believe that it can. This concept is known as the economy’s “potential growth rate” and it represents the fastest GDP growth rate achievable over time without stoking inflation. The Federal Reserve believes that potential growth is 1.8% consisting of 0.8% growth in the labor force combined with 1.0% growth in productivity. We suggest that potential growth is in the process of climbing to perhaps 2.5%. We combine 0.8% growth in the labor force with 1.7% growth in productivity. In the past year productivity has climbed by 1.3%. If investment spending climbs by 3.0% or more this coming year, productivity growth can easily climb to the 1.7% mark.

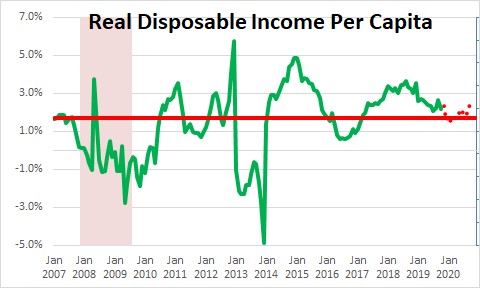

Faster potential growth is also important because it will accelerate growth in our standard of living. If GDP grows 0.7% more quickly (2.5% versus 1.8%), then income will also grow 0.7% more rapidly. Economists use real disposable income per capital as a measure of our standard of living. Over the past 30 years this income measure has climbed at a 1.6% pace. If we are right that potential growth is going to be 0.7% faster than it was previously, then our standard of living can easily grow at a 2.3% pace.

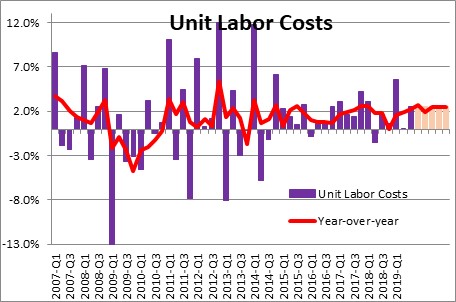

If the economy going forward is going to expand at a 2.5% pace, won’t inflation rise? A little. When forecasting inflation we typically start with the labor market because labor costs represent two-third of a firm’s overall cost. If wages begin to climb, employers may pass along those higher costs to customers in the form of higher prices. But that is only part of the story. Growth in productivity can affect how much of those higher labor costs get passed along. If firms raise wages by 3.7% and its workers are no more productive, its labor costs have risen 3.7% and it probably will try to raise prices. If they pay 3.7% higher wages but its workers are 3.7% more productive firms do not care because they are getting 3.7% more output. In this case they have no reason to raise prices. Thus, the way to judge the extent to which higher labor costs impact inflation is to look at labor costs adjusted for the change in productivity which economists call “unit labor costs”.

With the economy at full employment wages have begun to rise. In the past year worker compensation has accelerated from 2.0% to 3.7%. Productivity has risen 1.5%. Thus, unit labor costs — labor costs adjusted for the change in productivity – have climbed 2.2%. Our expectation is that in 2020 compensation will increase 4.2% and productivity will climb by 1.7%, so unit labor costs will rise 2.5%. The Fed has a 2.0% inflation target. As we see it, a 2.5% increase in unit labor costs should generate a modest amount of upward pressure on the inflation rate.

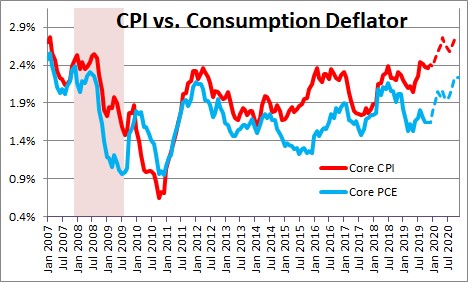

Specifically, we look for the core CPI to rise 2.7% in 2020 versus 2.4% this year. We refer to the core CPI because it is the most widely known measure of inflation. However, the Fed’s specific inflation target is the core personal consumption expenditures deflator which tends to grow about 0.5% more slowly than the CPI. Thus, we expect the Fed’s targeted inflation rate to climb 2.2% in 2020. The Fed has a 2.0% inflation target. Given that this inflation measure has fallen short of its 2.0% target consistently since the expansion began in 2009, we think the Fed will actually welcome a rate that is slightly above target. Its goal seems to be to have inflation average 2.0% for the business cycle as a whole.

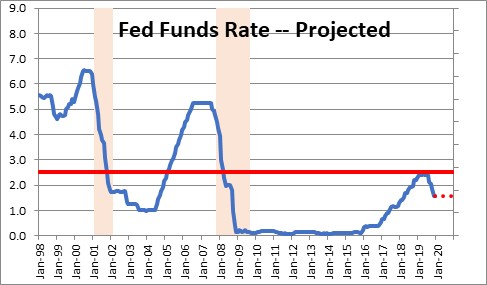

If GDP growth in 2020 climbs to 2.4% and its targeted inflation measure rises 2.2%, the Fed will leave the funds rate unchanged in a range from 1.5-1.75%. From its viewpoint that outcome is near perfect – moderate 2.4% GDP growth, full employment, and an inflation rate that is near its target at 2.2%.

That same combination of moderate GDP growth, well-controlled inflation, and very low interest rates is certain to propel the stock market upwards. We look for a double-digit gain next year to at least the 3,500 mark for the S&P 500 index.

For most of the expansion’s 10-1/2-year duration economists have frequently believed that a recession was in sight. Every time they have been wrong and we think they will be wrong once again. If the Fed is going to leave rates unchanged through the end of next year, there is no way this recession ends prior to 2021, and there is no reason to think it ends then. That means this expansion can easily last for a dozen years or more. The previous record was the decade of the 1990’s. That expansion lasted exactly 10 years. This one is going to blow through that previous record.

The Fed constantly gets criticized. It may be raising rates too quickly, or perhaps not lowering them fast enough. A lot of that comes with the territory. Usually the criticism is civil. However, Trump’s attacks on the Fed (Chair Powell in particular) is both vicious and unwarranted. If the Fed can engineer an expansion that lasts at least 12 or 13 years – the longest expansion on record – it is doing a superb job and should be complimented, not ridiculed.

We hope all of you have a wonderful holiday season. Thank you for joining us as we analyze the economy’s ups and downs each week during the year. Let’s hope that 2020 turns out to be as good as we anticipate.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Steve,

Great read….again!

Looking forward to see you hopefully in the new year.

Let us know when you are in NYC!

Jerry

Thanks so much for another year of great analysis and advice. Your optimistic outlook is both accurate and appreciated.

Thanks Bruce. So far, so good. Hopefully we can keep it going in 2020. Have a great Christmas.

Steve

Hi Jerry. Nice to hear from you and thanks for the kudos. Let’s hope we can keep it going in 2020. Have a great Christmas.

Steve

Hello Steve-

As always I love your analysis and breakdown of the numbers!

Thank you so much for sharing your wonderful insight for 2020!

Toula

Thanks Toula. Just like the old days!