December 10, 2021

As we see it, 2022 is likely to be characterized by surprisingly robust GDP growth (4.9%) and inflation is almost certain to remain far higher than the Fed would like to see (4.8%). But because the Fed continues to believe that the recent run-up in inflation is caused by supply chain disruptions and not by excessive growth in the money supply, it still concludes that the flare-up in inflation is ”temporary”. As a result, it is inconceivable that it will choose to aggressively fight inflation any time soon. It may well raise rates three times in 2022 which would boost the funds rate from near 0% today to 0.75% by the end of 2022, but it would still be far below its “neutral” level of 2.5%. Fed policy will remain stimulative for years to come. The combination of robust GDP growth next year, a substantial increase in inflation, and still low rates will keep corporate earnings on a roll and the stock market soaring.

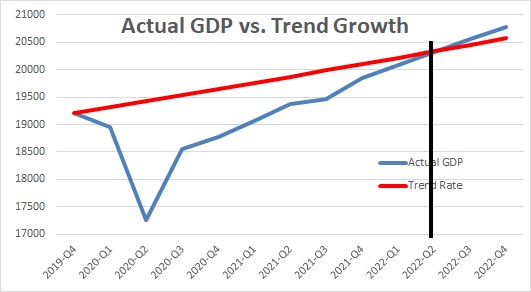

The recession in March and April of 2020 was caused by federal government action. It chose to fight COVID by shutting down the U.S. economy. As a result GDP growth in the second quarter plunged by 31% and fell $2.2 trillion below its potential growth path. Twenty-two million Americans lost their jobs. Given that government action was the cause of the recession our leaders in Washington felt an obligation to make people whole. But they overdid it. The combination of $5.3 trillion of stimulus checks and $4.2 trillion of Fed purchases of securities have provided $9.5 trillion of stimulus to counter a $2.2 trillion shortfall. No wonder the economy has been on a roll, and because much of that excess liquidity remains, we are bullish on the 2022 outlook and anticipate GDP growth of 4.9%.

In addition to excessive stimulus, the tech sector played a pivotal role in lifting the economy out of recession and we believe that economists have underestimated its importance. For example, think of the bio-tech sector and the development of the COVID vaccine. Vaccine development is typically a 10-year process but the COVID vaccine was developed in a single year thanks to technology.

When the economy was shut down a firm could not meet face-to-face with its employees. Sales people could not meet face-to-face with their clients. But along comes Zoom to allow them to approximate face-to-face meetings when they could not otherwise do so.

During the pandemic consumers could not go to their local stores to shop. They had to buy things on line. Amazon was well positioned to do that but, with the help of technology, brick-and-mortar stores like Wal-Mart and Target did a wonderful job of educating their customers to order on-line and pick up their merchandise at the store.

Many people were sick. No one wanted to sit around in a doctor’s office amongst a bunch of other sick people waiting to see a doctor. Along came tele-health.

In-restaurant dining was eliminated. In order to survive restaurants had to develop delivery or take-out services. Along came UberEats and Grubhub to fill the need.

Tech played a critical role in helping the economy emerge from recession, and will continue to help it adapt to this significantly revamped and ever-changing economic environment. We are confident that technology will help the U.S. economy’s speed limit climb from 1.8% currently to 2.5% or more in the years ahead.

Our relatively optimistic view of the economy next year could become unraveled if COVID resurfaces. We do not expect that to happen despite the recent appearance of the Omicron variant. When COVID arrived in early 2020 it had a pool of 330 million unvaccinated Americans as prime candidates to infect. But today 233 million Americans have received at least one dose of the vaccine and another 48 million have already contracted COVID and have developed natural immunity. Thus, 281 million people now have some sort of immunity which means the pool of potential candidates for COVID to attack has shrunk to 49 million, and COVID spreads almost exclusively amongst the unvaccinated population. We are not immunologists but our sense is that Americans will become progressively less fearful of COVID as the year progresses and it will cease to be a significant factor in determining the economic outlook.

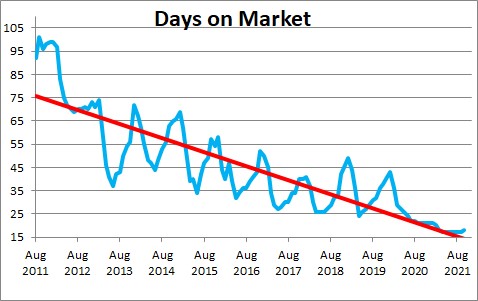

If one can eliminate COVID from the confluence of factors likely affecting GDP growth in 2022, the rest of the economy appears poised for growth. The demand for goods and services far exceeds supply in virtually every sector of the economy. For example, in the housing market properties fly out the door once they are listed. The typical property sells in 17 days which is the shortest length of time between listing and sale on record.

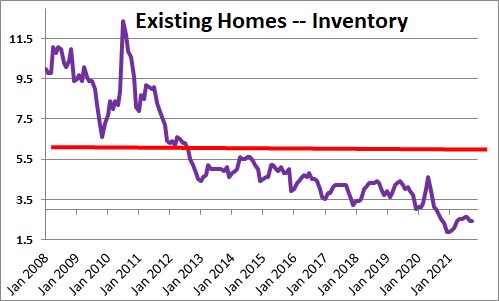

Because properties have been selling so quickly, realtors have only a 2.5 month supply of homes available to show potential buyers. They need roughly a 6.0 month supply for demand and supply to be in balance.

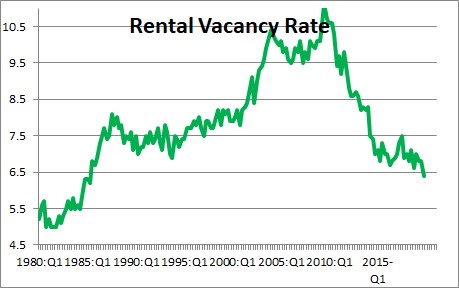

There is a similar shortage of rental properties on the market. The vacancy rate for rental units is the lowest it has been since the 1980’s. Thus, there a significant shortage of both single-family homes and apartment units.

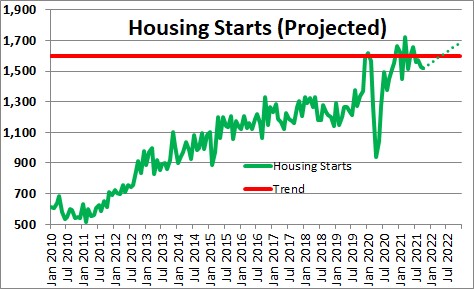

The solution is for builders to step up the pace of construction. But they are hampered by both a shortage of skilled workers and an inability to get required materials in a timely manner. While the pace of construction will accelerate, it will be impossible for builders to eliminate the substantial backlog of demand during this coming year.

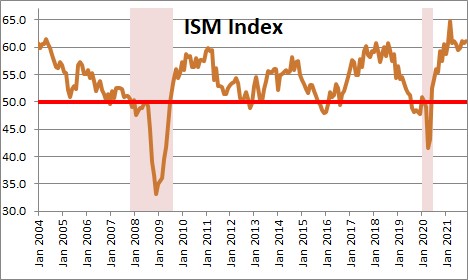

Manufacturers are facing similar difficulties. The Institute for Supply Management’s index for the manufacturing sector is near a record high level. Orders keep flowing in. Firms step up the pace of production as best they can, but they suffer from supply side constraints – delays in getting required materials, the high cost of raw materials, a shortage of critical inputs such a semiconductors, delays at ports, a shortage of truck drivers, a shortage of warehouse space, and an inadequate supply of skilled labor.

As a result, manufacturing firms have been forced to dig dip into inventories to satisfy as much of the demand for orders as they can. In the first three quarters of this year, inventories subtracted 1.6% from GDP growth. But eventually these supply issues will be resolved and the economy will receive a tailwind of roughly that same 1.6% in 2022.

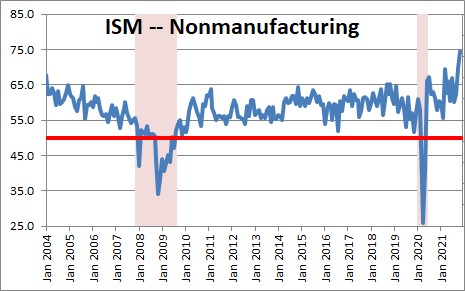

The Institute for Supply Management’s index for the service sector was at a record high level in October. It blew through that previous high by almost five points in November to establish an even more impressive record high level of 74.6.

Throughout this past year firms have complained about an inability to get the number of workers they need. Help wanted signs are posted everywhere. Job openings have soared to a record high level and, indeed, there are more job openings in the U.S. (11.0 million) then there are unemployed workers (6.9 million).

Part of the problem firms are having is that roughly 1.5 million of their former employees appear to have retired. Given massive gains in the stock market and rapidly rising home prices older Americans may be seizing the opportunity to downsize and use their newfound wealth to fund retirement.

Others appear to have rejected the idea of working for someone else and are, instead, choosing to venture out on their own by becoming gig workers or starting their own business. Since the recession ended in April 2020 “payroll employment” has increased by 18.5 million workers. “Civilian employment” (which is derived from a separate survey and is used in calculating the unemployment rate) has climbed by 21.8 million. Civilian employment includes not only workers on a company’s payroll, but also self-employed workers. Typically these two series move in tandem despite monthly wiggles. But that is not the case currently. The impressive gains in civilian employment have caused the unemployment rate to fall far more rapidly than anybody expected. It now stands at 4.2% which is a shade above the Fed’s estimate of the full-employment threshold of 4.0% at which point everyone who wants a job has one. That level should be reached by January 2022.

As a result of all of the above, we anticipate GDP growth of 8.0% in the fourth quarter followed by a 4.9% pace in 2022. If those growth rates are accurate, any remaining slack in the economy will be eliminated by the second quarter of 2022.

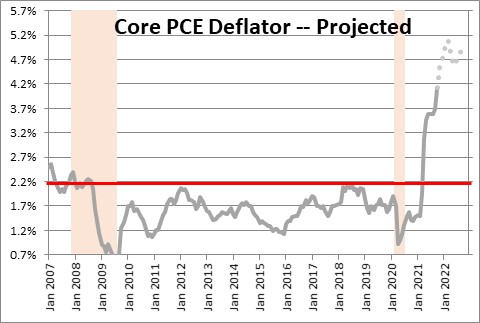

With no remaining slack and the economy continuing to expand at a 4.9% rate, far in excess of its potential growth rate of 1.8%, inflation is not going to retreat to the 2.0% pace the Fed would like to see any time in the foreseeable future.

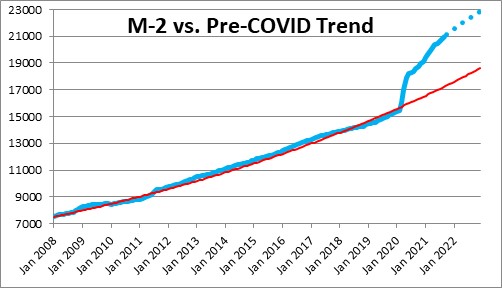

Ever since the recession ended in April of last year the Fed has been hawking the notion that the recent run-up in inflation was caused by the supply constraints and once they ran their course inflation would quickly retreat to the targeted 2.0% mark in 2022. We reject that idea because money supply growth is soaring. Back in the 1970’s Milton Friedman won a Nobel Prize for concluding that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” For years money growth was steady at about 6.0%. But when the Fed bought $2.5 trillion of securities in March and April of last year, money growth soared and the Fed has continued to purchase securities since then. As a result, the gap between the current level of the money supply and the level consistent with its 6.0% trend rate has widened to $3.8 trillion. That represents surplus liquidity just waiting to get spent. When the economy was mired in recession, surplus liquidity was a good thing and helped get the economy back on track. But today with the economy at full employment that surplus liquidity will only serve to boost the inflation rate.

For what it is worth, we expect the personal consumption expenditures measure of inflation to rise 4.9% next year. It will not return to the Fed’s targeted 2.0% pace until such time as the Fed gets serious about fighting inflation. That time is not on the foreseeable horizon.

Ever since the recession ended in April 2020 the Fed has concluded that the flare-up in inflation would be temporary. In early December the Fed concluded that the supply chain issues were not being resolved as quickly as anticipated and, as a result, inflation might remain elevated for some time to come. But it still believes that the inflation jump is caused by supply chain difficulties. It makes no mention of growth in the money supply as a possible catalyst. For a central bank to be unconcerned about growth in the money supply is unimaginable.

Given its view about the cause of inflation it is inconceivable that the Fed might begin to act aggressively to fight inflation in 2022. Early in the year it will have met its two goals of full employment and inflation somewhat about its 2.0% targeted pace. That sets the stage for perhaps three rate hikes in 2022 which would put the funds rate at 0.75% by the end of that year. Another four rate hikes in 2023 would boost it to 1.75%. The Fed will not achieve a “neutral” funds rate of 2.5% until late 2024. Thus, the Fed has no intention of becoming serious about its desire to tame inflation for years to come.

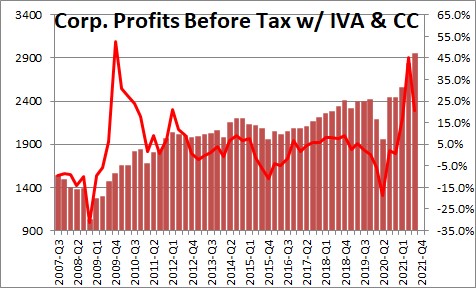

With robust GDP growth next year, an increase in the inflation rate (which will give firms some pricing power), and still low interest rates, corporate earnings should soar. In the past year firms have experienced an increase in the cost of raw materials, sharply higher transportation costs, and higher wages. Despite those challenges corporate earnings have risen dramatically. In the decade prior to the recession corporate earnings grew 7.0% annually. In the six quarters since then they have climbed at an impressive 23.7% pace.

As we see it, 2022 should be characterized by 4.9% GDP growth, 4.9% inflation, and a modest increase in the funds rate to 0.75%. Thus, the outlook for 2022 appears particularly bright. If the Fed raises rates as slowly as we envision, it may ultimately have to raise the funds quickly to a point far above the 2.5% neutral level to corral the steady increase in the inflation rate. At that point the danger of recession will increase. But that is a worry for some year beyond 2024. Rest easy for now.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Just curious, are you ever worried? We can print trillions, run away inflation etc and nothing ever matters? So why ever raise rates. Leave them low for the next 900 years and keep this going. Cmon.

Thanks for your comment Gary. I am negative when the economic situation seems to warrant it. But that time is not now. The title of the article is “The Year Ahead” 2022″. That is the time frame I was referencing and I do think the economic looks good for both 2022 and 2023. I will become negative when the Fed becomes serious about fighting inflation. But given where they have been coming from — having grossly underestimated growth in both the economy and inflation — I doubt they will suddenly become inflation fighters any time soon. I also suspect that will not get the funds rate above a “neutral rate” until 2024. With a presidential election in that year it would be surprising that the Fed would risk becoming a factor in the election. The Fed is far behind the curve and inflation will remain well above target. But at some point it will have to catch up. When it does the expansion will be at risk. But that time does not appear to be any time soon. I thought I made that fairly clear in the last paragraph.

Steve Slifer