June 22, 2018

The trade war talk seems to be escalating. First, Trump imposes tariffs on steel and aluminum imports. China strikes back. Then he then announces tariffs on an additional 200 products. China responds. Meanwhile, Mexico retaliates. The E.U. plans to levy tariffs on American favorites like bourbon, Levi’s, motorcycles, and orange juice. Canada, Japan, and Turkey are preparing similar measures. Where does all this end? We do not know. Our president tends to be mercurial and can say one thing one moment but change his mind the next. The reversal of his policy on separating families at the border is the most recent case in point. For this reason, we do not want to overreact.

It is important to remember that nobody “wins” a trade war. All countries lose. Having said that, some countries are hurt more than others.

Those of us living in the United States are relatively isolated. Our economy is huge, and trade is only a small part of it (about 10%). Thus far, the tariffs have largely affected those companies that use steel and aluminum as inputs in their production process. But if the tariffs broaden and begin to ensnare consumer goods like autos and electronic products, the howls of protest will get louder as prices rise at Walmart, COSTCO, and auto dealerships, and the potential damage will increase.

Before trying to assess the possible damage, it is important to recognize that the U.S. economy is on a roll. Following moderate 2.0% GDP growth in the first quarter, growth in the second quarter should approach 4.0%. That is roughly a 3.0% pace in the first half, compared to 2.2% growth in 2017. At the same time the future looks bright. Stock markets should be at record high levels. But let’s look closer.

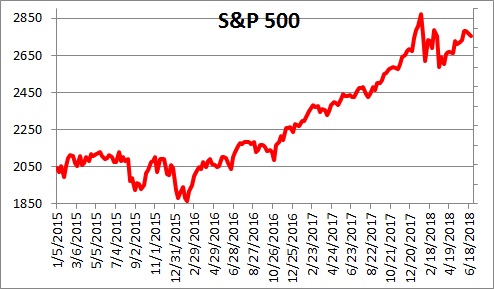

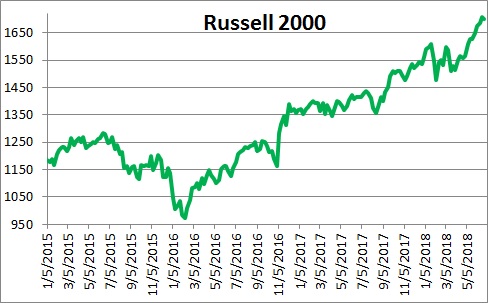

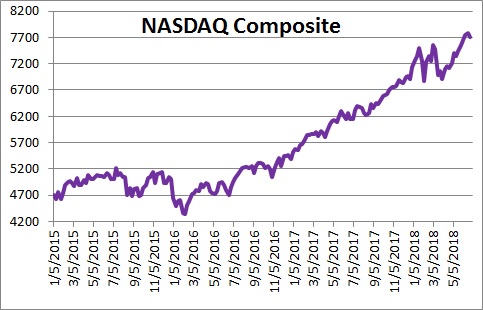

To get a feel for how trade is impacting companies within the United States compare the performance of the S&P 500 index to the behavior of the Russell 2000 and the NASDAQ Composite.

The S&P 500 index reached a record high level in January, dropped about 10%, and has been struggling to re-attain its previous high. What is included in the S&P are many large multi-national companies which will be negatively impacted by tariffs. It includes the winners (largely the steel and aluminum companies), and the losers (which include auto manufacturers, makers of metal cans for beer and soda, industrial machinery and equipment makers, transportation equipment manufacturers –think airplanes. trucks, busses, and motorcycles). There are a lot more of the latter than the former. The S&P 500 index has done well, but not nearly as well as other stock market indexes.

The Russell 2000 is a small-cap stock market measure. Companies in this index have no direct exposure to tariffs. This index is at a record high level.

The NASDAQ Composite Index is heavily weighted towards technology and internet stocks and includes tech giants like Apple, Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and Facebook. It, too, is at a record high level.

Thus, it seems to us that the mediocre performance of the S&P 500 — in contrast to that of small firms and tech companies — suggests that the already imposed tariffs on steel and aluminum, and the additional tariffs currently under consideration, have had a moderate negative impact on this stock market measure.

Tariffs can also impact the U.S. economy through a faster rate of inflation as the prices of imported products rise. This one is, in our opinion, somewhat more troublesome. A broad trade war could result in, say, a 10% increase in the prices of imported goods. A price hike of that magnitude which affects 10% of the economy could tack on 1.0% to the inflation rate. But inflation is already under pressure from wage hikes caused by the tight labor market, rising rents associated with the shortage of available housing units, and upward pressure on commodity prices. As it stands we expect the core CPI to rise 2.5% in 2019. But tack on an additional 1.0% and boost it to 3.5%, and the Fed would almost certainly raise rates more quickly. Thus, more rapidly rising interest rates could become the catalyst for the next recession. But let’s not overreact. Nothing is imminent, and we expect that eventually these trade issues will be resolved because it is in the best interests of all parties. Let’s hope President Trump understands that.

Outside of the U.S. the potential impact is more pronounced. Given that the United States has a goods trade deficit of $800 billion, tit-for-tit tariff hikes will end up hurting other countries more than the U.S. Tariffs impact these countries in the same two ways as in the U.S.

First, they weaken GDP growth. Their exported products become considerably more expensive for U.S. residents to purchase, which reduces exports growth and slows the pace of economic activity.

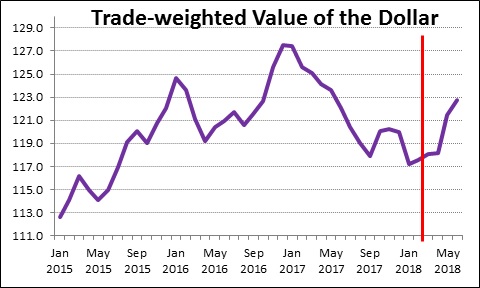

Second, if economic growth in the U.S. strengthens relative to other countries, the dollar strengthens. In fact, the trade-weighted value of the dollar has risen 4.5% since Trump announced his steel and aluminum tariffs on March 1. The dollar has risen across-the-board amongst our five largest trading partners – China, Canada, Mexico, Japan, and Europe. Of note was the 9.4% appreciation against the Mexican peso, a country that would be hit hard by the demise of NAFTA. The Canadian dollar has depreciated by 3.2%. The dollar’s ascent was enhanced by significant gains against a broad spectrum of emerging and developing economies –15.5% versus the Brazilian real, 10% against the South African rand, 14.5% against the Russian Ruble. Because commodities are traded in dollars, a rising value of the dollar means the dollar-prices for the goods they purchase to support their factory-based economies rises, which boosts the inflation rate. And as the prices of their inputs rise their demand drops, which exacerbates the negative impact on their economy.

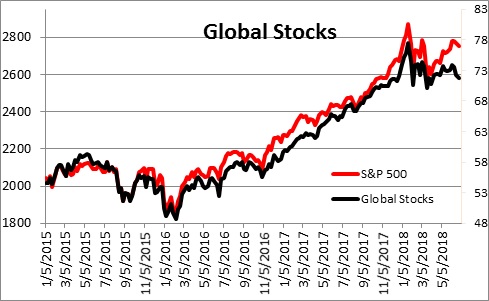

The combined effect of slower GDP growth and higher inflation is reflected by movements in their stock markets. Since the beginning of March when the steel and aluminum tariffs were announced the S&P 500 index has declined 1.0%. The MSCI All World Index has declined 4.0%. The non-U.S. drop was not in Europe where stocks declined a modest 1.0%. Nor was it in the U.K. or in Japan where, in both cases, stock prices rose 6.0%.

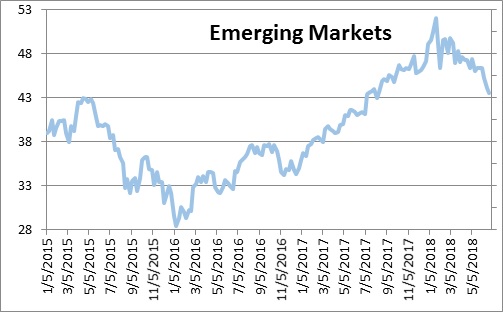

Rather, the drop was concentrated in the stock markets of emerging economies. The MSCI Emerging Markets index fell 12%. This series includes giant – but still emerging – economies like China and India and a long list of smaller countries like Brazil, Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia Mexico, Russia, South Africa, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates.

Could these declines be attributable to factors other than trade? Possibly. But the declines noted above have occurred since the initial steel and aluminum tariffs were announced in early March and trade talk has dominated the headlines. The sad thing, in our opinion, is that this damage was inflicted by bad trade policy in the United States. We supported the administration’s corporate tax cuts earlier in the year, but we oppose tariffs which counter much of the positive impact from the tax cuts.

We do not want to overreact to short-term changes in stock market values – in the U.S. or elsewhere. But stock market values do reflect the fear of the potential damage that would be inflicted by a protracted trade war.

Let us repeat – nobody wins a trade war. With an $800 billion trade deficit in goods the potential fallout on other countries will be greater than in the United States, but do not for a moment believe that the U.S. economy will be unscathed.

Because one half of that $800 billion trade deficit in goods occurs with one country – China — we would support policy changes that force the Chinese to respect intellectual property rights in the form of copyrights and patents, and policies that encourage them to buy more U.S. goods. But we cannot support policy initiatives that hurt our neighbors and allies who have done no wrong. This makes no sense.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Thanks. You take it way beyond the price of a Harley in Paris or Moscow.