November 1, 2013

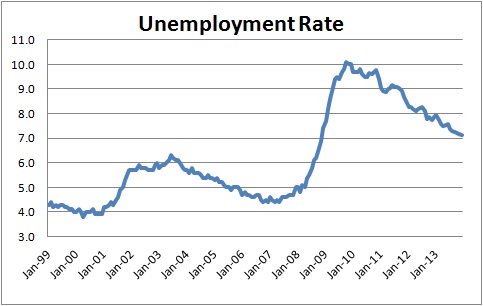

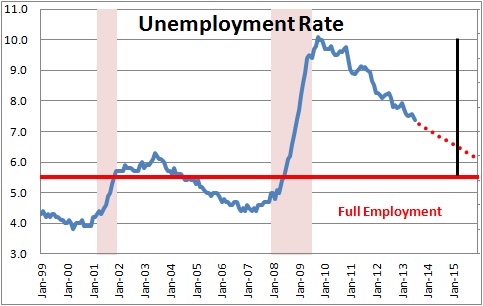

In September the unemployment rate was 7.2%. Throughout 2013 the unemployment rate has fallen more quickly than expected. At the beginning of this year, for example, the Federal Reserve thought that the unemployment rate at yearend would be 7.6%. It is already below that level and may decline further between now and December.

But how can an economy that is producing only modest increases in employment see a relatively rapid decline in the unemployment rate?

The short answer is that there are fewer people than expected looking for jobs. Think about how the unemployment rate is calculated. The Bureau of Labor Statistics divides the number of people who are unemployed by the number of people in the labor force.

Typically, the labor force grows at roughly the same rate as the population. With population currently growing by 1.0% one would expect the labor force to be growing at the same 1.0% pace. That implies that job gains of 130 thousand per month are required to keep the unemployment rate steady.

But lately labor force growth has slipped to 0.3%. As a result, the economy has needed to produce only 40 thousand jobs per month to keep the unemployment rate steady. With monthly jobs gains well in excess of that amount the number of unemployed workers has been falling by 70 thousand per month and the unemployment rate has been declining rapidly.

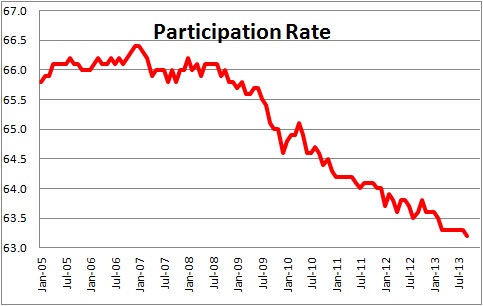

Why is the labor force growing so slowly? To answer that question economists typically look at something called the “participation rate” which is simply the number of people that have jobs or are actively seeking employment calculated as a percent of the labor force. Prior to the recession that number had been steady at about 66%. Since late 2008 when the economy collapsed that rate has been steadily declining and now stands at 63.2%.

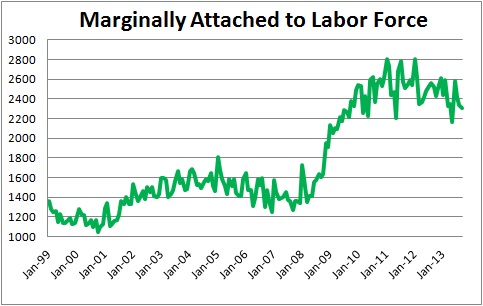

Some economists argue that the decline in the participation rate reflects people who have been unemployed for so long that they have given up looking for a job. As a result, they are no longer counted as part of the labor force. That is, at best, a partial explanation for the decline in the participation rate. Today there are 2.3 million people that have given up looking for a job. Prior to the recession it was averaging about 1.5 million. If all of the additional 0.8 million people gradually began to look for a job, labor force growth in 2013 might be 0.2% higher. That means it would 0.5% versus 1.0% growth rate in the population. Something else far more important must be going on and there is. The baby boomers are retiring.

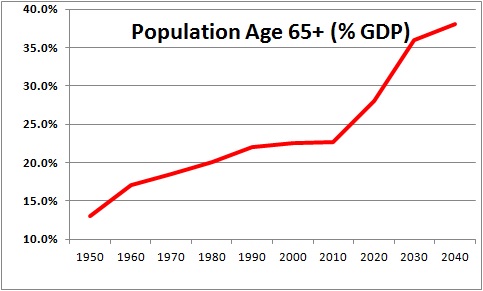

The baby boomers were born between 1946 and 1964. If one adds 65 years to each of those numbers, one would expect the baby boomers to retire between 2011 and 2029. Indeed, the Congressional Budget Office estimates that the number of retirement age Americans will climb from 22.6% of GDP in 2010 to 28.0% by 2020. That suggests slower growth in the labor force of about 0.5% per year. To us this represents a far more important factor in determining the recent slow growth of the labor force and the corresponding decline in the participation rate than the discouraged worker theory.

Because this process will continue every year from now through 2029 the U.S. economy may need to generate only about 60 thousand jobs per month for the next several years to keep pace with growth in the labor force. If employment continues to climb by 130 thousand, the unemployment rate will decline steadily.

At such a pace the unemployment rate will fall to 6.5% by the end of 2014. The 6.5% mark is important because the Fed has told us that it intends to begin raising short-term interest rates once the unemployment rate has fallen to that level. Earlier this year the Fed thought the unemployment rate would not reach the 6.5% mark until mid-2015. It now expects that to happen by the end of next year. While the Fed may not begin raising short rates at precisely that moment in time, the point is that the first Fed move to raise short-term interest rates appears to have shifted forward by perhaps six months because of the more rapid than expected decline in the unemployment rate.

That does not imply that Fed policy will be unchanged until that time. It will probably slow its pace of bond purchases from $85 billion per month currently by March of next year, and should stop buying bonds altogether prior to the end of 2014. That will push long-term interest rates higher. So while the Fed may be slower than expected in the timing of its first move to taper its bond purchases which will raise long-term interest rates, the faster than expected decline in the unemployment rate suggests that the delay will be of short duration and will be followed fairly quickly by higher short rates.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, SC

Follow Me