February 3, 2017

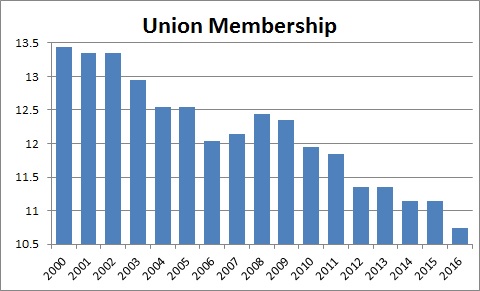

Union membership continues to slide. It declined 0.4% in 2016 to 10.7%. This is not a new trend. Union membership has been on a steady downtrend since 1945 when roughly one-third of employed people belonged to unions. By 1983 when the Bureau of Labor Statistics began collecting data, there were 17.7 million union workers which represented 20.1% of the workforce. By 2000 that percentage had shrink to 13.4%, and now it stands at 10.7%. Here in the Charleston area Boeing workers will vote on February 15 on whether or not to join the International Association of Machinists. Boeing workers need to understand that they are fighting a trend that has been underway for 70 years. Increasingly, workers across the country have decided that they are not getting their money’s worth from union representation and are opting out.

There are a variety of reasons for this decline. Automation is high on the list, as many labor-intensive jobs have been replaced by machinery. The shift in the economy from being manufacturing based to services is another. Unions have traditionally been strong in manufacturing with large plants, and weaker in the service industry with much smaller firms. Indeed, in the mid-1970’s the manufacturing sector represented 25% of the U.S. economy. Today manufacturing jobs are just 9% of the total. Also, many traditional union jobs have been shifted overseas to take advantage of lower wages.

More recently union membership is under attack from a number of different states and cities as those governors and mayors have figured out they simply cannot afford to pay for gold-plated benefits packages that the unions successfully negotiated in days gone by. The movement away from unions started in Indiana in 2012 but spread to Michigan in 2013. Michigan was a huge blow for union leaders because it is generally regarded as the birthplace of the modern labor movement. Then came Wisconsin in 2015. In 2016 West Virginia became another right to work state and that was followed by Kentucky in January of this year. In all, there are now 28 right-to-work states. In right-to-work states workers may join a union if they choose to do so, but they are not obligated to join the union and automatically have union dues deducted from their paycheck.

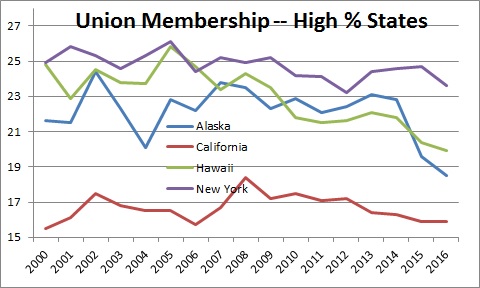

States where union membership is the highest are New York at 23.5% followed by Hawaii at 19.9% and Alaska at 18.5%. Since the year 2000 union membership in Hawaii and Alaska has declined slightly but, in contrast to the steady erosion in union membership at the national level, membership in New York and California has stayed quite steady.

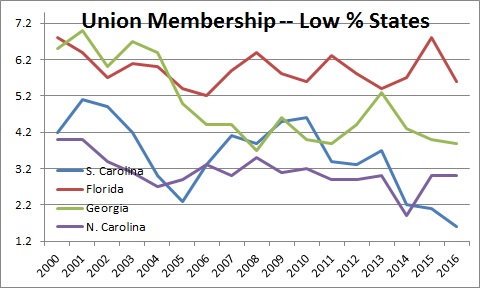

At the other end of the spectrum, South Carolina has the lowest rate of unionization at 1.6%. It is followed fairly closely by North Carolina at 3.0%. Georgia and Florida are also near to the bottom of the totem pole with union membership rates of 3.9% and 5.6%, respectively.

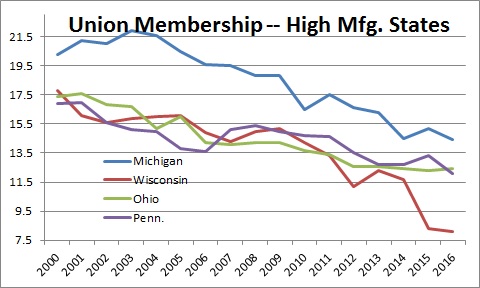

The biggest declines in union membership have occurred in states which have a large manufacturing presence — like Michigan, Wisconsin, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. As a result of automation and outsourcing of jobs overseas, union membership in Ohio and Pennsylvania membership has fallen 3-5% since 2000. The decline is far more pronounced in Michigan (7%) and Wisconsin (10%) which became right-to-work states in 2013 and 2015, respectively.

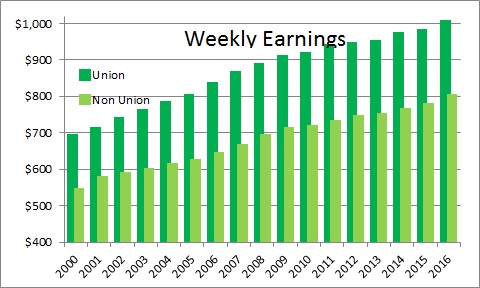

Unions have been extremely successful in attracting higher wages and benefits for their members when compared to comparable earnings amongst non-union workers.

In 2016 union members earned $1,004 per week which is 25% higher than the $802 earned by non-union members. Given these high wages it is not surprising that many companies are choosing to move to “right-to-work” states where union membership is not required. Other companies are choosing to respond by moving operations offshore. In some sense, the unions’ success is now leading to the steady contraction in membership.

That wage differential largely reflects gold-plated benefits packages for both pensions and health care. But someone pays for those higher labor costs. In the case of governments the burden is born by the taxpayers. When economic conditions are less than favorable and state and local governments are forced to lay off workers to shrink bloated budget deficits, those governors and mayors have got to go after the unions and do what they can to trim those benefits and/or weaken union power. They have had considerable success in recent years most notably in Wisconsin, Indiana, Michigan, West Virginia, and Kentucky. With each successive victory other government officials work up the courage to take on the unions in their state or city.

Any way you slice it, union power is weakening in a hurry.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me