May 3, 2019

Perhaps the biggest economic surprise of the past year has been the stubbornly low inflation rate. Over the course of the past year the Fed’s preferred inflation measure, the personal consumption expenditures deflator (excluding the volatile food and energy components) has risen 1.6%. The Fed’s target is 2.0%. Fed Chair Powell has indicated that the 2.0% inflation goal is “symmetric”. Given that inflation has generally run below target for most of the past six years, the Fed would welcome a 2.5% inflation rate for a period of time so that it averages 2.0% throughout the expansion. But how exactly can it make that happen? To say it wants 2.5% inflation is one thing. Achieving it is something else.

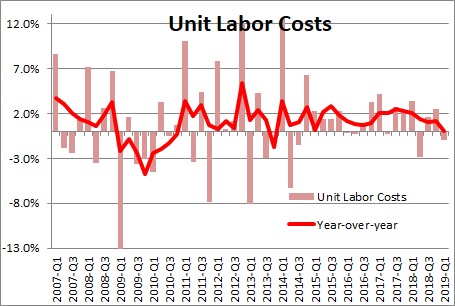

As we see it, two factors are responsible for the currently low inflation rate. First, labor costs adjusted for the change in productivity, or what economists call “unit labor costs”, have been essentially unchanged over the past year. That comes about from a 2.5% increase in compensation almost entirely offset by a 2.4% increase in productivity. From a business viewpoint, employers are paying their workers 2.5% high compensation, but they are also getting 2.4% more output. Business leaders are satisfied with that outcome. Basically, workers have earned their fatter paychecks. In the 10-years since the recession ended, unit labor costs on average have risen 1.0%. In today’s world this means that wages can grow about 1.0% more quickly than they are currently without boosting inflation.

But if the Fed only has control over interest rates, how exactly can it entice firms to lift wages? If for a short period of time the Fed chooses to pursue a 2.5% inflation rate it might actually like to see unit labor costs rise by 2.0% or so, presumably consisting of wage gains of 4.5% offset by 2.5% growth in productivity. But how exactly does it entice firms to bump worker pay from 2.5% currently to 4.5%? It does not have the tools to do that.

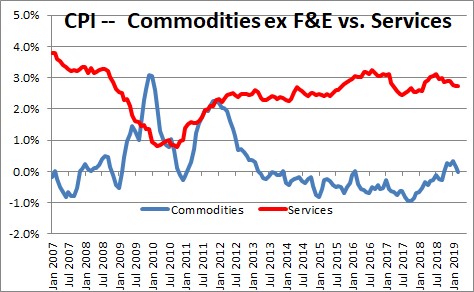

The other factor keeping inflation in check is technology. When we want to buy anything in today’s world from a car to a toaster, we search the internet to find the lowest price available. As a result, goods-producing firms today have absolutely no pricing power. If we split the CPI between goods and services, goods inflation in the past year has been unchanged while service sector inflation has risen 2.7%. Put it all together and in the past year the core CPI has risen 2.0%. The Fed might like to see inflation 1.0% or so higher than it is currently but it still has the same problem – how can it make that happen?

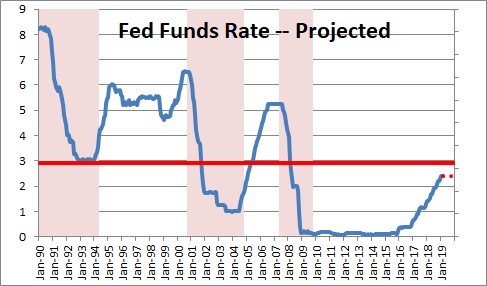

Some have argued that the Fed should lower the funds rate. But that would be ill-advised for a couple of reasons. First, the funds rate is already relatively low. The Fed has recently lowered its estimate of a “neutral” funds rate from 3.0% to a range of 2.5-3.0%. The current funds rate is in a range from 2.25-2.5%. Thus, the current level of the funds rate remains low and is not in any way constraining growth. Lowering the funds rate does not seem like the right solution.

Second, if the Fed could somehow make the economy grow faster and inflation accelerate, the bulk of the inflation pickup would likely be in services. Presumably, given technology, the goods sector of the economy will have little ability to raise prices for the foreseeable future. If the Fed tries to boost the inflation rate by 1.0% it might end up with goods inflation still at zero percent, but with service sector inflation of 4.0-4.5%. Is that what it wants? That does not see like a desirable solution either.

As we see it, if the economy can continue to grow at something close to a 3.0% pace and the inflation rate remains steady at 1.6% or 0.4% below the 2.0% target, what is the matter with that? That strikes us as being a situation that is sustainable for years to come. An expansion that endures for an additional three, four, or five years beyond its already-achieved 10 years of growth would be an ideal outcome. Why in the world would the Fed choose to make adjustments that could possibly short circuit the current delicate balance between growth, inflation, and interest rates? That makes no sense. Stick with the plan and keep rates steady! Even Trump might like the eventual outcome.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Great analysis, thank you. But a close-to-3% annual growth cannot be sustained, especially last year’s figures are based on a round of significant tax cut. With the recent slowing corporate earnings, it’s not hard to see a lower growth rate for years to come; which will, subsequently, hold rates steady. The danger is the impatient and exaggerated nature of Wall Street, another massive drop similar to last December will put a real dent in consumer confidence and could easily derail economy, as well as DJT re-election efforts.

Last but not least, something has puzzled me for a long time, hope you could kindly shed a light with your vastly superior knowledge. With an ever increasing wealth/income disparity, the have-nots and not-have-muches have probably spend their majority of ‘wealth’ on the basics, the wealthy class can only spend so much to compensate the other 99%’s lack of spending. Is this another reason for low inflation?