September 29, 2023

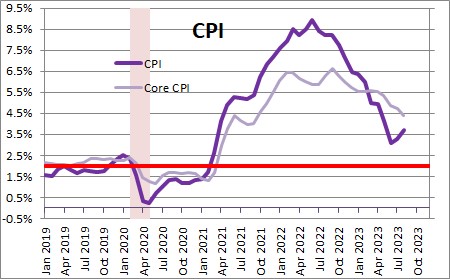

When inflation first started to rise in mid-2020 the Federal Reserve told us that we did not need to worry because it was “temporary” and attributable to supply constraints that led to notably higher — but temporary — increases in prices. Economists are used to “temporary” factors affecting the inflation rate. Oil prices might surge if a pipeline is damaged. But, eventually, the damage is repaired and oil prices fall back to where they started. Ditto for food prices. A summer drought might push food prices higher, but a few months later a new crop arrives and prices return to where they started. Because of the volatility of these two components of inflation and their ability to distort the underlying rate of inflation, economists routinely exclude them in their calculation of the so-called “core” rate. But their definition of temporary is typically a few months. In this case, the core inflation rate continued to climb until reaching a peak of 6.5% two years later in March 2022. The Fed says it is determined to get it back to the 2.0% mark but it does not envision getting there until 2025 — five years after inflation began to climb. Never once does it suggest that it wants the inflation rate to decline for a while to return to its original 2.0% path. As a result, prices today are far higher than they would have been in the absence of the pandemic-induced recession. We see higher prices across the entire spectrum of goods and services – gasoline, food, shelter, cars, hotel room rates, restaurants. Three years later the core inflation rate is far higher than it would have been if prices had climbed at a steady 2.0% rate in the absence of the recession. This is devastating for lower-income families and for individuals living on a fixed income. Getting inflation back down to the 2.0% mark is not good enough. It needs to decline for a while to counter some of the cumulative buildup from the long-lasting run-up in inflation. The Fed has no intention of letting that happen.

The CPI fell for a few months once the recession began in March 2020. But the recession only lasted two months and as the economy re-opened growth surged in the third quarter. Manufacturers were unable to ramp up production fast enough to keep pace with demand. Supply shortages emerged everywhere. Container ships were stacked up at the nation’s ports waiting to unload. Not surprisingly, prices surged. The Fed believed that the accelerating rate of inflation would be “temporary”. But unlike the case with “temporary” increases in food and energy prices, the core inflation rate never declined. The only thing that happened is its growth rate slowed from a peak of 6.5% to 4.4%. The Fed has stated that it wants to get inflation back to its 2.0% targeted rate, but it has no intention of reversing any of the permanent run-up in inflation.

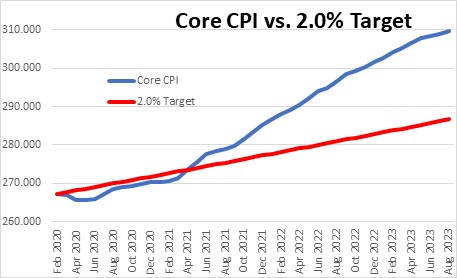

If the core CPI had continued to grow along the targeted 2.0% path every month since February 2020 (the month prior to the onset of recession), the CPI would have climbed along the path shown in red below. The actual level of the core CPI is in blue. Its current level is 8.0% higher than it would have been in the absence of the recession. An item that sold for $267 in February 2020 would cost $286 today if inflation had risen 2.0% in the interim. Instead, it costs $309 today because of excessive inflation. It is impossible to characterize the behavior of inflation in the past three years as “temporary”.

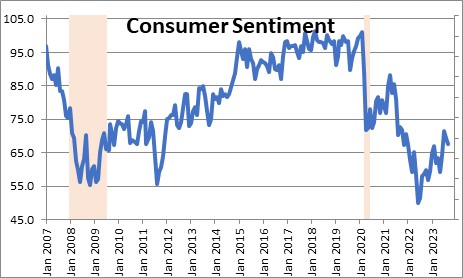

The level of consumer sentiment is extremely low. It remains lower today than the low point reached in the 2020 recession and is only slightly higher than the low point reached in 2008-09 recession. When asked about the source of their pessimism consumers frequently cite rising prices in general and prices for groceries and gasoline in particular. Given the inflated levels of the core CPI index described above, it is easy to understand why sentiment is depressed.

Inflation hurts everyone. It erodes the consumer’s purchasing power. If someone takes $100 into the grocery store today they might leave with two bags of groceries. A year ago their $100 might have allowed them to purchase three bags of groceries. Unfortunately, the ones hurt the most are those at the lower end of the income scale and those relying on a fixed income. They cannot easily avoid rising food and energy prices and higher rent which consume a very large portion of their take home pay.

If the growth rate for the core CPI continues to slow from 4.4% currently to 3.0% or so by the end of next year consumer sentiment may rise, but it is hard to imagine it climbing to the vibrant levels that existed prior to the recession. To make that happen, we will likely need to see the core CPI decline for a while. Given the Fed’s stated intention, that is unlikely to happen any time in the foreseeable future.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Hey Stephen!

1. Any observations on WHY the FED is taking this strategy for managing long term inflation? (Or have they just not said anything about it?)

2. And, is there a metric calculation for “a while”?

Hi Patrick.

The only way for prices to actually decline, would be for the Fed to induce a recession. That is not a desired outcome either. If they get inflation to 2.0% and keep it there, we will eventually adapt to the recent run-up in prices. But that will take a while — like years. Also, given that higher prices for some items are attributable to higher wages for restaurant workers, teachers, retail clerks, etc. who have long been underpaid, isn’t that a good thing even if it results in a one-time jump in prices? Does the Fed really want to induce a recession and throw those same people out of work? Tough choices.

Re: the length of “temporary” there is nothing official re: that length of time. Depends on the source. A pipeline leak? Probably a couple of months. A drought might last just during the 3 summer months. But it might also last 3 years — in which case it should not necessarily be regarded as temporary. I guess you know “temporary” when you see it. But determining how long it might last can be tricky.