May 31, 2013

At some point the Fed will take its first step towards tightening and begin to remove some of the surplus liquidity in the banking system. While that time is getting closer, this policy change will probably not occur until around yearend.

To understand this process, one needs to understand the two parts of Fed policy.

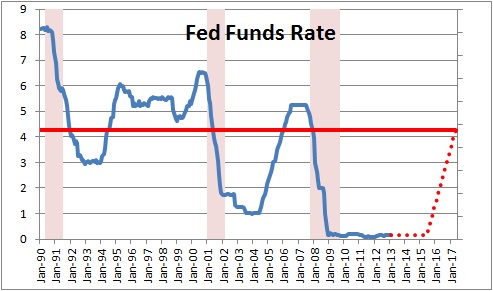

First, the Fed has tight control over short-term interest rates. The federal funds rate is the rate at which banks trade reserves amongst each other. Banks with surplus funds lend them to banks with shortages at that rate which is currently about 0%. That rate is not going to stay there forever. The Fed thinks the funds rate would be neutral when it is about 4.25%. So once that rate begins to move, it has a long ways to go. But the Fed will proceed cautiously. It is likely to take them two years to raise short-term interest rates from 0% to 4.25%. The Fed has told us that process will begin once the unemployment rate falls to 6.5%. It is currently 7.5%. The unemployment rate will not reach 6.5% until the end of 2014.

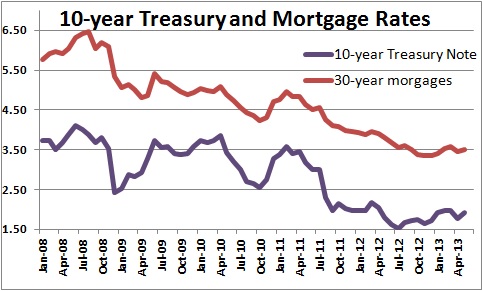

Second, when the economy tanked in 2008 following the demise of Lehman Brothers the Fed lowered the funds rate to 0.0% by December of that year. That was conventional Fed policy. But the economy clearly needed additional stimulus so the Fed decided to try an experiment and buy long-dated Treasury securities and mortgages in an effort to push long-term interest rates lower and provide support for the ailing housing market. They had never done this before. Thus, this became very unconventional Fed policy. While the Fed does not have as tight control over long-term interest rates, they succeeded in lowering 10-year rates from about 4.0% to a low of 1.7%, and mortgages from 6.5% to 3.5%.

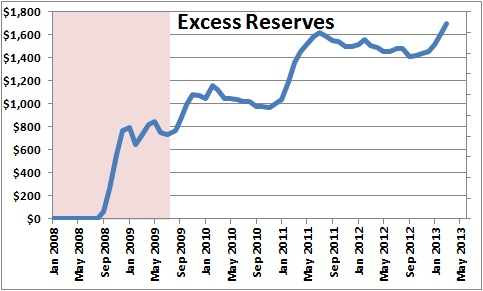

To do this they bought securities from banks and placed the proceeds of the sale into the banks’ checking account at the Fed which is known as their reserves account. Effectively, they flooded the banking system with reserves. Surplus reserves climbed from $2 billion at the end of 2008 to their current level of $1.7 trillion today and the Fed is still buying $85 billion of such securities every single month. Thus, each month they further stimulate the economy.

This process must eventually end and the Fed needs to remove those surplus funds from the system. But when do they start?

The most important ingredient in determining that start date will be the performance of the economy. Fueled by a rapidly rising stock market, rapidly climbing home prices, and job gains of 200 thousand per month, the economy seems to be gathering momentum. We expect GDP growth of 2.4% in the first half of 2013, 2.9% in the second half, and 3.2% in 2014. If this forecast is accurate, once the Fed sees more rapid GDP growth later this year it may feel comfortable enough to begin reducing surplus reserves. A minority of Fed officials make the case that it should begin this process immediately.

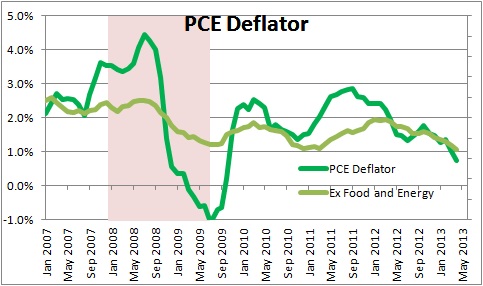

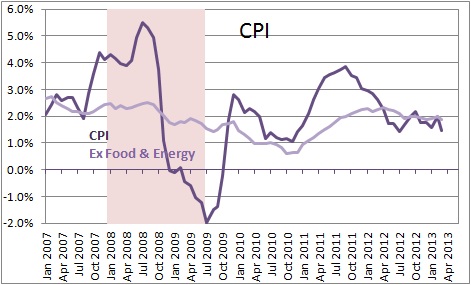

But there is more to the story. The Fed also has an inflation target of 2.0%. Its favored measure of inflation is the personal consumption expenditures deflator excluding the volatile food and energy categories which has risen 1.0%. This is one-half of the desired pace of inflation. Is this a problem? Probably not.

Other inflation measures, most notably the CPI, are telling a somewhat different story. The CPI excluding the volatile food and energy categories has risen 1.7% which is much closer to the Fed’s target. Why the big difference between the two inflation measures? The CPI measures price changes for a fixed basket of goods each month. Hence, it is a pure measure of price changes. The deflator captures both price changes and changes in consumer behavior. If consumers switch from buying butter to margarine to save money, the deflator would register a smaller increase than would the CPI.

Some Fed officials have latched onto the slowness of inflation and argue that the Fed should be buying even more securities. But given the less dramatic drop-off in the CPI those people remain a minority. The Fed should be alarmed if prices in the U.S. began to fall. Consumers would postpone purchases today because those goods would be cheaper tomorrow. This is much the situation Japan has been in since the mid-1990’s. Once a deflation mentality sets in, it is very difficult for a central bank to change it. But our sense is that the odds of that happening in the U.S. are near 0%.

Given this uncertain economic outlook we believe the wisest course for the Fed is to do nothing until that situation becomes clearer. It will get to that point eventually. If our forecast for fourth quarter GDP of 3.1% is accurate the Fed may feel sufficiently comfortable to take that first step later this year.

When they do, neither the stock market nor the bond market is going to like it. Stocks have been fueled in part by the notion that the Fed was on their side and nothing bad was going to happen. Suddenly that idea will change. The bond markets will realize that this is the absolute bottom for interest rates. If rates rise, bond prices will decline.

But what is important is that none of this policy change will take place quickly. It will take several years for rates to get to a point where they might bite and actually begin to slow the pace of economic activity. In some sense the Fed will be merely taking its foot off the accelerator. It won’t hit the brake for several more years. Its job now is to convince the markets that it does not intend to move quickly.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, SC

Follow Me