December 14, 2011

(Almost) As Good As It Gets

This is the time of the year when economists reveal their expectations for growth in the upcoming year. Our best guess is that 2011 will look quite different from 2010 as the economy shifts into high gear. Specifically, we look for the following:

- GDP growth should be 4.0% this year versus 2.7% in 2010.

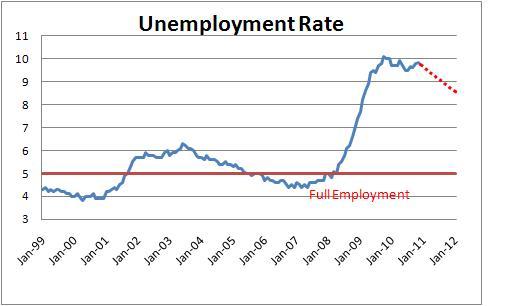

- The economy will soon start producing 250 thousand jobs per month, and the unemployment rate will end this year at 8.7%.

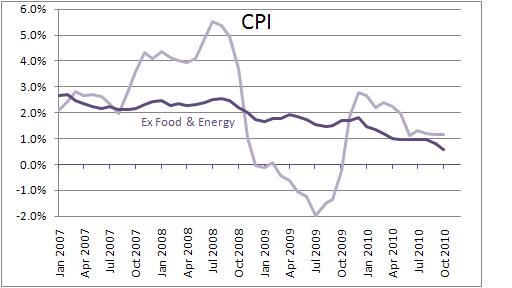

- Inflation will remain subdued with core inflation averaging 1.1%.

- The Fed will leave rates unchanged throughout 2011.

Indeed, the economy in 2011 will be impressive. While the unemployment rate will remain elevated, it will at least begin a steady decline which should bolster confidence.

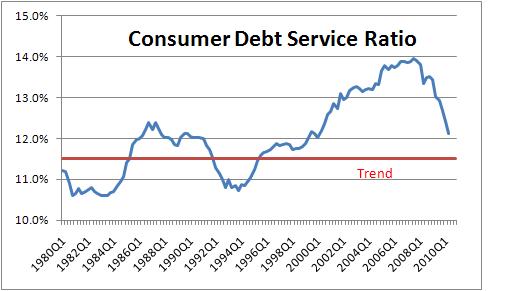

When talking about the economy it is best to break it up into its major components. Let’s start with the consumer. Consumer spending is critical because it represents about two-thirds of GDP. So goes the consumer, so goes the economy. At the beginning of the recession consumers were saddled with debt payments which surged to 14.0% of income. But in the past two years they have been paying down debt with a vengeance. Mortgages, credit card debt and car loans have declined almost every month. As a result, that ratio has plunged to about 12.0%. How much farther must it fall before consumers are “comfortable” with their debt burden? Over the past 30 years that ratio has averaged 11.5%, so perhaps one could argue that represents a comfortable amount of debt. If so, we will get there by midyear.

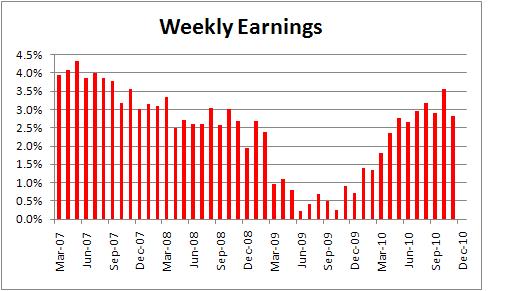

In recent months employment has begun to increase, people are working longer hours, and hourly earnings have been climbing. The net result of all this is that weekly earnings are growing at nearly the same pace that they were climbing prior to the recession.

If income is rising and consumers are becoming more comfortable with their debt burden, then it stands to reason that their pace of spending on goods and services of all sorts (including housing) will accelerate as we move throughout 2011.

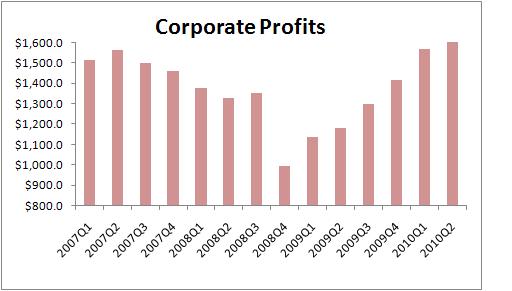

How about the businessman and the outlook for investment spending? During the recession firms laid off eight million workers. Once the recession ended corporate America began to invest heavily in information technology and any type of productivity-enhancing equipment. Indeed, spending on technology has grown at a 15% pace since the recession ended in June 2009. It is by far the fastest growing sector of the economy. Productivity growth has surged. As a result, firms made a lot of money! Corporate profits today are back to where they were prior to the recession.

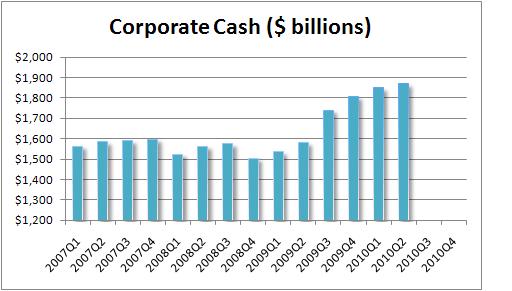

Because of the rebound in profits, corporations have socked away unprecedented amounts of cash. Funds slopping around in checking accounts, time deposits, and U.S. Treasury securities have climbed $350 billion in the past year and are at a record high level. This cash is not going to sit there for long. Corporations will be looking for investment opportunities. Much of it will be spent on technology. More cash might be spent gobbling up a rival or paying down debt, but both of those events are likely to propel the stock market higher.

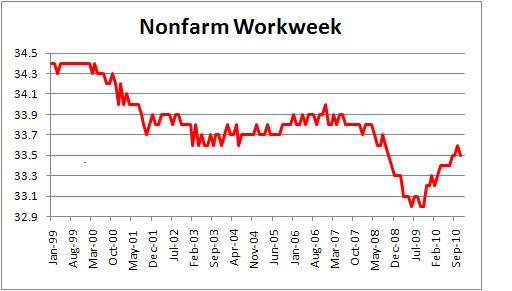

The one missing ingredient during 2010 was jobs. But the employment situation now seems brighter. In response to demand, firms have had to step up production. Rather than hire new workers they have, for the most part, chosen to hire temps and work existing employees longer hours as evidenced by the steady increase in the workweek which is now almost back to its pre-recession level. Between health care benefits, vacation time, pensions and 401 (k) plans, it is expensive to hire permanent employees.

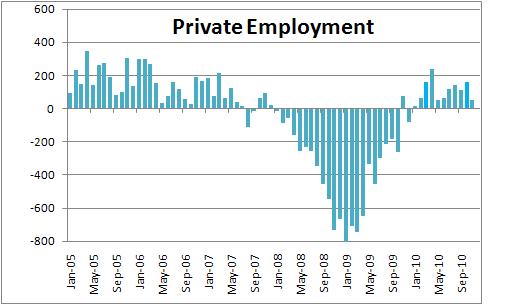

But now firms have pushed that string about as far as it can go and they need to hire additional bodies. Think of it this way. If GDP is rising at a 2.5% pace, and productivity is also rising at 2.5%, then the economy can grow at that rate forever without the need for additional hiring. Firms can produce everything that they need to produce with their existing headcount. But if, as expected, GDP growth quickens to 4.0% and, simultaneously, productivity growth slows to 1.0%, then the gap must be filled by employment growth of the difference, or 3.0%. If you work through the math that means that monthly employment gains could quickly climb to 250 thousand per month. Over the most recent three month period, payroll employment has on average risen 107 thousand. If we soon begin to see monthly gains of 250 thousand, more people will be working which means faster growth in income, a pickup in spending, consumer and business confidence will soar, the unemployment rate will – at long last – establish a steady downtrend, and corporate profits will climb further. In short, we will have the beginnings of a virtuous economic cycle.

If we begin to see employment gains of the magnitude suggested, the unemployment rate should decline to 8.7% by the end of 2011. That is a lot higher than where it ought to be, but at least it will have started to move in the right direction. At 250 thousand jobs a month it will take years to replace the eight million jobs lost during the recession.

What about inflation? If we start to see steady GDP growth of 4.0%, won’t inflation soon come roaring back? Probably not. The Fed expects the inflation rate to remain in check for the foreseeable future primarily because of “slack” in the economy. There are two types of slack to which they are referring.

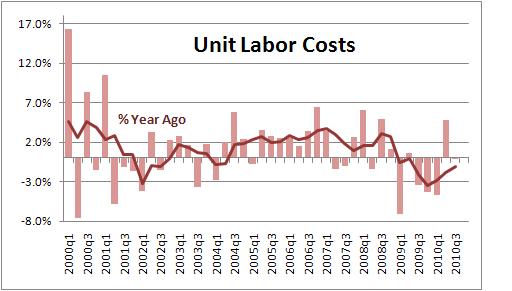

First, with the current unemployment rate at 9.8% when it should be at 5.0%, there are lots of available workers for every job. Thus, there is a lot of “slack” in the labor market. That competition amongst workers will ensure that wage pressures remain in check. But what is really important to an economist is a concept called “unit labor costs” which is basically labor costs adjusted for the change in productivity. For example, if I pay you 3.0% higher wages, you might think that my costs have risen by 3.0%. But what if you are 3.0% more productive? I pay you 3.0% more money but I get 3.0% more output, so I really don’t care. In this case, “unit labor costs” are unchanged. As shown in the chart below, unit labor costs continue to decline. As a result, we do not expect any upward pressure on the inflation rate stemming from labor costs this year. That is important because wages represent about two-thirds of a firms overall cost of production.

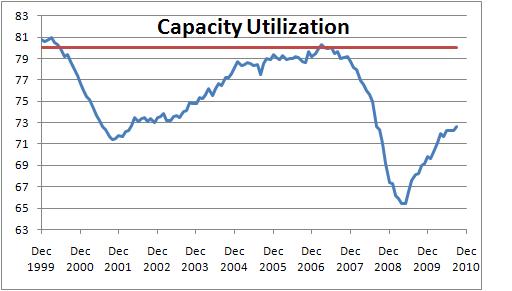

The other type of “slack” in the economy comes from utilization rates in the industrial sector. Once capacity utilization climbs to about 80%, we typically see a somewhat higher rate of inflation. At that point the economy is running so hot that firms are able to push through price hikes. However, the utilization rate in the manufacturing sector today is 72.7%. Factory output typically slows in the second year of expansion. If so, then capacity utilization will remain well below the 80% danger level throughout 2011.

Between the slack in the labor market and a low utilization rate, it is hard to see inflationary pressures emerging for some time to come. As a result, we expect the core inflation rate this year to be 1.1% versus 0.6% in 2010.

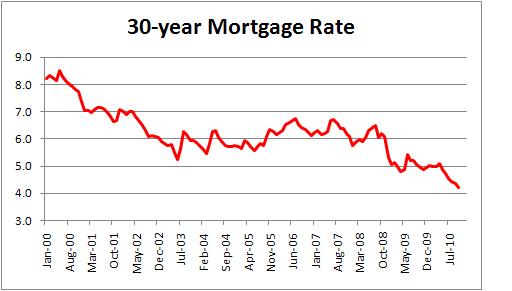

If you are in the Fed’s seat, what do you do? Currently, the Fed believes GDP growth in 2011 will be in a range from 3.0-3.6% (versus our projected 4.0% pace) and the unemployment rate will end the year at the 9.0% mark (compared to our 8.7% forecast). It is actively trying to stimulate the economy by purchasing $600 billion of longer-dated U.S. Treasury securities between now and midyear in an attempt to push long-term interest rates lower. Our guess is that the yield on the 10-year Treasury note will not dip much below its current level of 2.5%, which means that the 30-year mortgage rate will remain at about 4.25% — which happens to be a record low level.

Eventually the Fed will have to get interest rates back to “neutral” which means that the funds rate will need to climb from its current level of around 0% to about 4.5%. But given the slack in the labor market and the low utilization rate, there is no need for the Fed to begin tightening until sometime in 2012. Thus, our expectation is that the funds rate will remain in a range from 0-0.25% throughout this year, but 2012 will be a different story.

If this is the world that evolves – GDP growth accelerates to 4.0%, we start cranking out 250 thousand or more jobs a month, the unemployment rate remains high but begins a steady decline, the inflation rate remains in check because of that slack in the economy, and the Fed leaves the funds rate at 0-0.25% for the entire year – we are all going to be fairly happy campers.

As with any forecast there are always risks. But just keep in mind that the world is very different now than it was in 2008. The global economy has pulled out of its slump and is gathering momentum. Financial firms are not nearly as highly leveraged as they were at the beginning of the recession. Consumers and corporations have been aggressively paying down debt. Corporations have accumulated an unprecedented amount of cash. The global economy, the U.S. in particular, is far better positioned to withstand difficulties should they arise in 2011 than it was a couple of years ago.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, SC

Follow Me