May 7, 2021

Payroll employment rose 266 thousand in April which was far smaller than the 950 thousand increase that had been expected. Firms are struggling to find an adequate number of workers to satisfy the growing demand. To a large extent the shortfall can be traced to an increase in the nonfarm workweek. Every month employers can choose to hire more workers or work existing employees longer hours. Being unable to find enough willing workers, firms in April choose to work current employees longer hours. The 0.1 hour increase in the workweek in April has the same effect on production as hiring an additional 412 thousand workers. In other words, if workers were more readily available, payroll employment in April would have risen 678 thousand – not 266 thousand. Even so, that is still shy of the 950 thousand increase that had been expected. We suggest that business leaders encountered a shortage of workers who were willing to work rather than stay home and take advantage of generous unemployment benefits. Reducing worker incentives to remain on the sidelines is key to creating more jobs and allowing the unemployment rate to fall more quickly.

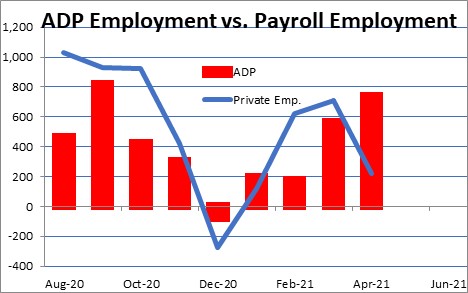

At first blush the considerably smaller-than-expected increase in employment in April is hard to understand. The ADP employment report for April released two days earlier showed an increase in employment of 742 thousand, not even close to the 266 thousand increase in BLS data.

Respondents in the Institute for Supply Management’s surveys for manufacturing and service sector firms consistently talk about an inability to hire enough workers because of worker absenteeism, short-term shutdowns of production due to part shortages, unqualified workers, and competition from generous unemployment benefits. The April shortfall in employment is not the result of any shortage of demand. It reflects problems in attracting an adequate supply of workers.

A large part of the explanation lies in the lengthening of the workweek by 0.1 hour in April from 34.9 to 35.0 hours. Every month employers have a choice. They can hire more workers or they can boost production by working current employees longer hours. A 0.1 hour increase in the workweek may not sound like much, but it reflects an increase of 0.286%. Had they been able to find enough qualified and/or willing workers, payroll employment would have jumped by an additional 0.286% or 412 thousand workers. Rather than a miniscule increase in employment of 266 thousand, payroll employment would have risen by a much more robust 678 thousand. While still short of the 950 thousand increase that had been anticipated, it least makes some degree of sense.

With payroll employment still 8.2 million workers below its pre-pandemic high one would think that hiring workers would not be a problem. Similarly, with the unemployment rate at 6.1% which is far higher than the 3.5% level that existed prior to the recession hiring generally should not be a problem. But it is.

So what is going on? We believe that the primary culprit is the availability of extremely generous unemployment benefits. According to the BLS state unemployment benefits average about $318 per week. Federal benefits are an additional $300 per week. Weekly benefits of $618 works out to average of $15.45 per hour. Available jobs at restaurants, bars, retail shops, and delivery services are hard pressed to compete with such generous benefits. In many cases the available jobs are hard work and require long hours. Why bother? Stay home.

Some states like Montana and South Carolina have recognized the disincentive to work and emerging labor shortages created by generous unemployment benefits, and are choosing to end federal pandemic unemployment benefits for their residents beginning next month.

For the other 48 states these federal benefits are currently expected to expire in early September. If that truly happens, we expect to see much more sizeable increases in payroll employment in September, October, and November, and correspondingly large declines in the unemployment rate later in the year.

To counter this disincentive to work, some firms are offering higher wages to attract new workers. Amazon, Walmart, and COSTCO are boosting wages and offering bonuses in an effort to attract new workers and retain existing workers. Restaurant and bar owners are doing the same thing. As this practice spreads, average hourly earnings should continue to climb.

Prior to the pandemic average hourly earnings were rising at a 3.0% pace. In the past six months that has quickened to 4.4%. Higher wages will result in higher prices and faster inflation.

In short, the demand side of the economy is hot as home sales, car sales, and general consumer spending have been boosted by a series of stimulus checks. The savings rate currently is lofty at 27.8% which means that consumers are poised to spend at a frenzied pace for months to come. Employers are struggling to catch up and one of the primary reasons that is the case is the disincentive to work created by very generous unemployment benefits. If the Federal government wants to see the unemployment rate fall quickly, these benefits are not helping.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Hi Steve,

I agree with your comments, however I’d add health care benefits, perceived health risks and child care as issues. Even if someone would like to work, the economically rational decision for many people who would take a pay and benefit cut for rejoining the work force so is to do unofficial “side gigs” or just stay home. If we had some sort of national health care plan and other first world country benefits we’d probably not have this issue. We’d have different issues, but the economy would probably be doing better.

I enjoy working, I have a productive work life that I find fulfilling that matches my education. Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem that most people don’t view a low wage, low benefit, dead end career at McDonalds the same way. I can’t blame them for wanting to delay the return to that existence as long as possible.

Be careful assuming cost-push inflation. if prices rise it is due to an increased demand or a reduction in supply. This is a period of rising demand and intermittent supply issues. So rising wages do not raise prices since supply is increasing.

Hi Bill,

Thanks for taking the time to comment. I agree that if inflation is on the rise, it will be driven primarily by a sharp increase in demand. But if firms cannot hire an adequate number of workers and choose to offer higher wages to new and existing workers, and subsequently raise prices to offset those higher costs, it seems to me that we can get inflation resulting from both factors. It does not have to be an either/or situation.

Steve

Hi Chris,

All good points. But I wonder to what extent (and I do not know the answer to this) people are using those as excuses. “Oh, I am so worried about getting COVID and bringing it home to my kids.” At this stage of the game? Seriously? But how can you argue against that? It will be interesting to see what happens when (if?) the federal benefits run out.

I keep asking myself what I would do if I were a low income worker. Would I do the same thing? Honest answer — I don’t know. I like to think that my work ethic is such that (like you) I would want to get back on the job ASAP. But, honestly, I might not.

Given that we stopped the economy dead in its tracks last year but have been throwing money at consumers, we have created legitimate supply shortages in many sectors of the economy. If a manufacturing cannot get the goods they need to produce their product, it makes sense to me that hiring will lag until such time as the supply chains improve.

The real puzzle is the difference between the ADP report and the BLS jobs report. One was pretty good. The other not so much. The two series use different seasonal factors. I wonder to what extent this is a technical, seasonal adjustment issue? If firms were really having a hard time finding bodies, how come the ADP report showed such a big gain. Makes little sense. Only time will tell.

Steve