July 23, 2010

The rate of inflation has slowed to a pace not seen in 40 years, and some economists fear a period of deflation. That is not going to happen. We are in the midst of a period of disinflation, which simply means that the rate of inflation is slowing. For example, the core rate of inflation, which strips out the volatile food and energy categories, has slowed from 2.5% prior to the recession to 1.0% today. That is disinflation. Prices rise more slowly today than before. Deflation describes a situation whereby prices actually decline. From 1999-2005 prices of Japanese goods fell 0.5 per cent a year for seven consecutive years. That is deflation.

Deflation strikes fear in the heart of economists because it is nearly impossible to reverse. It is typically triggered by a sharp, prolonged drop in economy. Given the drop in demand, businesses cut prices to boost sales. As prices for their products fall, businesses are reluctant to hire workers or expand operations. Consumers soon begin to expect further price reductions and delay purchases in the hope of still lower prices in the future. This makes the economy fall even faster. It is difficult for the central bank to provide adequate stimulus. The faster prices fall, the higher inflation-adjusted rates rise, which reduces the willingness of consumers and businesses to borrow and spend. This type of deflationary spiral is scary, but it is not going to happen here.

First, inflation in the United States has not yet even begun to decline. As noted earlier, the core CPI has risen at a 1.0 per cent rate in the past twelve months. That is the slowest we have seen in 40 years, but it is still a long ways from actually declining. Japan experienced falling prices for seven consecutive years. We are not even remotely close to that.

Second, deflation is typically the consequence of a contracting economy — like we had here in the United States during the depression. The U.S. economy has been growing steadily for the past year. In the first year of expansion GDP will climb by 3.3 per cent, and final sales by 1.5 per cent. That is not as rapid as we might like but it is an acceptable pace, and the consensus appears to be for 3.0 per cent growth next year. Growth of that magnitude is hardly conductive to falling prices.

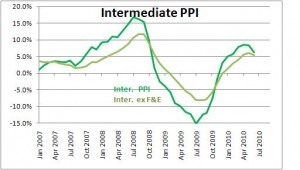

Third, the world’s second biggest economy, China, is growing at a 10.0 per cent pace. Rapid growth in this very large, manufacturing-based economy is putting significant upward pressure on commodity prices. That is clearly inconsistent with a deflationary environment.

Fourth, in an attempt to remain profitable, firms have been spending rapidly on information processing equipment and software. Such spending has risen 11.4 per cent in the past year which makes it the fastest growing sector of the economy. If firms were seriously worried about falling prices for their products, they would not make such investments.

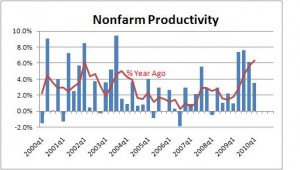

Fifth, as a result of such expenditures, productivity has risen 6.3 per cent in the past year. That is the biggest gain in productivity in the past 50 years! As a consequence, corporate earnings have jumped 35 per cent in the past year and are now back to levels that existed prior to the recession. Because they are making money, cutting costs, and hiring slowly, corporations are sitting on record levels of cash. Many plan additional productivity-enhancing expenditures during the next year.

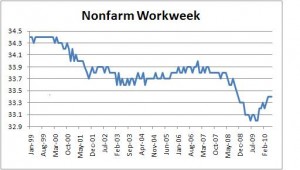

Sixth, firms have gone from laying off 750 thousand workers a month in the early part of 2009 to actually adding a few jobs in the first half of 2010. They are working existing employees longer hours and hiring temps, which are usually indicators of faster employment growth going forward. In contrast, Japanese corporations were having such a hard time making money during their period of deflation, that employment declined for six consecutive years.

Finally, given the 9.5% unemployment rate consumers are spending cautiously. But with each passing month they pay down more debt. By this time next year they should be sufficiently comfortable with their debt burden that they are able to accelerate their pace of spending.

Deflation headlines certainly get our attention, but it is hard to envision how the U.S. economy is going to get there.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, SC

Follow Me