September 18, 2020

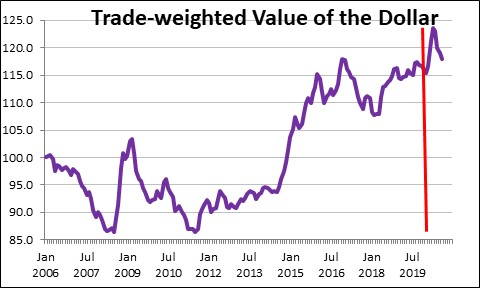

The dollar has been declining for the past several months. Some economists suggest that the decline reflects concern about the yawning budget deficit which will widen to $3,3 trillion this year and the associated increase in Treasury debt outstanding. Will foreign investors continue to purchase Treasury securities? Others suggest the dollar’s drop is a statement about the lack of confidence in the Trump Administration. Have foreign investors grown weary of the endless stream of tweets, the divisiveness, and his handling of the corona virus? Our sense is that the recent dollar drop was caused by the March/April recession and does not reflect either of those concerns.

The dollar has declined by about 5.0% since reaching its peak in April. But that conveniently ignores the dollar’s 6.5% increase from the end of last year through February. Indeed, today’s value is still 1.3% higher than it was at yearend. All financial instruments are volatile in short periods of time. Keep in mind that the dollar has experienced much more dramatic declines in recent years – a 17% drop between 2009-11, and an 8.5% decline in 2017-18. Its recent drop is minuscule by comparison.

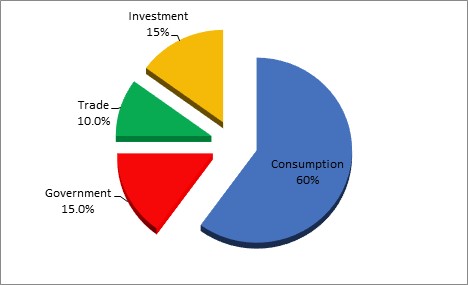

From a GDP standpoint the trade sector is only 10% of the overall economy. For that reason, any change in the value of the dollar needs to be both substantial and prolonged to have significant any impact on growth. The recent dollar drop is neither.

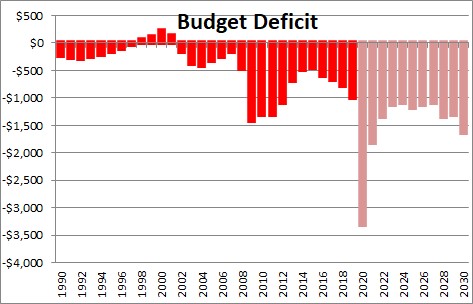

The fiscal stimulus has caused the budget deficit to explode and forced the Treasury to dramatically increase the amount of debt outstanding.

The government spent $3.0 trillion to pull the economy out of recession and it worked well. The recession appears to have lasted just two months. However, the additional government spending coupled with a loss of revenue has boosted the budget deficit from $1.0 trillion in 2019 to $3.3 trillion this year. This means that the Treasury will have to issue $3.3 trillion of debt to finance the budget gap for this fiscal year and additional amounts in excess of $1 trillion in each of the next nine years. Thus, Treasury debt issuance is poised to skyrocket.

Will the Treasury have to pay higher interest rates to finance that debt? Not much. The Fed has pledged to keep short rates at 0% at least through 2022 and they will probably stay there even longer. Inflation is not expected to rise appreciably any time soon. We expect the core CPI to increase 1.9% this year and 2.3% in 2021. If that happens the yield on the 10-year note may climb from 0.7% today to 1.4% by the end of next year. Long rates may increase somewhat during that period of time, but will still remain extremely low. Finally, the Treasury is expected to issue a 50-year bond next year which will lock in these low rates for a protracted period of time.

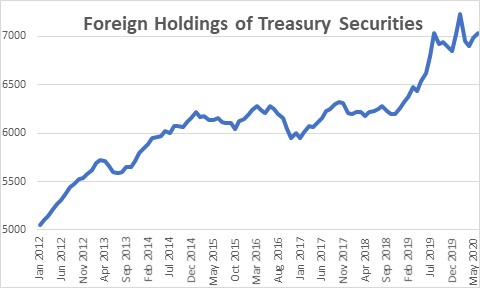

Could the dollar decline since February reflect foreign government reluctance to own U.S. Treasury securities? No. As shown below, central bank holdings of U.S. Treasury securities have been steadily increasing for years. However, between February and June foreign ownership of U.S. Treasury securities fell by $187 billion. But examining which countries cashed in some of the Treasury holdings can shed some light on the cause of the decline.

The two biggest owners of U.S. Treasury debt are Japan and China which between them own 1/3 of all foreign owned debt. China has been reducing its holdings of Treasury securities for the past several years as increased trade and political tensions between the two countries is causing them to diversify their asset holdings. That is not new. China’s holdings of Treasury debt should continue to shrink gradually for some time to come. And while Japan’s holdings declined in the February to June period, it steadily increased its holdings of Treasuries from October 2018 through January. It does not seem to be worried about owning Treasuries.

The $187 billion decline in foreign ownership of our debt between February and June is not generally where you would expect it. China and Japan reduced their holdings by a total of $25 billion. Saudi Arabia shrunk its holdings by $60 billion as oil prices collapsed. The U.K. trimmed its holdings by $31 billion as it dealt with its own problems at home. Brazil dumped $21 billion for the same reason. Another $20 billion came from Canada and $15 billion from tiny Singapore. For the most part it appears that the central banks that cashed in some of their holdings of Treasury securities needed liquidity to deal with the impact of the global recession on their own economies. Keep in mind that the selling occurred exclusively in March and April. In May and June foreign central bank holdings of Treasury securities increased and erased about one-half of its earlier decline. It would be a serious mistake to interpret the recent drop in foreign ownership of U.S. Treasury debt as a statement of concern about the magnitude of dollar debt outstanding or concern about the U.S. political situation. It was caused by the global recession and the associated need for liquidity.

Will the dollar lose its status as the world’s reserve currency? No. The concern about central banks selling their holdings of U.S. Treasury securities is usually focused on China and what happens if it suddenly chooses to sell its $1.1 trillion of Treasury securities. But China’s economy is largely export driven. This means that every month Chinese exporters receive dollars as payment for their goods sold to the U.S. Those firms then sell the dollars they receive to get the local currency required to pay their workers. While Chinese ownership of U.S. Treasuries may shrink gradually in the months ahead, a precipitous decline is out of the question unless there is a dramatic drop in trade between the two countries. That seems unlikely. China needs a significant volume of trade with the United States to keep its economy going.

Furthermore, if a central bank does not want to hold dollar-denominated assets and chooses to sell them, where exactly will they place the proceeds?. Chinese yuan? But China could freeze their holdings if relations between the two countries deteriorate. Japan? It has not exactly been an engine of growth for many years. Europe is having a very rough time recovering from the corona virus and Brexit. Bitcoin? Hardly. Not with its volatility. While central banks may not like the way the U.S. is running its country and the political gridlock, the alternatives seem worse.

The U.S. currently has enough problems with an election 2 months away, difficulty in getting the virus under control, and now a Supreme Court battle. The modest dollar decline is not a cause for alarm.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Steve,

I agree with you completely. Additionally other than our ego, the dollar dropping isn’t really a bad thing. Our exports are cheaper, and imports are more expensive. While that lasts it helps bring back the domestic economy. We have a only a few areas with substitution problems, such as rare metals.

I wonder if the Fed statements about holding the interest rates lower for years might keep the dollar lower for a while to come? I would imagine some people moving to hold some reserves offshore to get better returns on interest if they think the dollar will remain fairly stable or even decline a bit more.

Best

Thank you Stephen for creating such a clear, understandable explanation of the current financial situation. I really appreciate your insights.

Hi Darrel,

I really do think people make far to much of relatively small wiggles in the dollar. We have far more important issues to deal with right now. Sounds like the election and the Supreme Court have, at least temporarily, replaced COVID as the top problems. Ahhhh, what would the world be like without something to worry about? Best.

Steve

Hi Chris,

It seems to me that everybody looks at changes in the dollar from the U.S. viewpoint. Like you said, a weaker dollar makes our exports cheaper, and boosts the price of imports which in today’s world is a good thing if it can boost inflation. But for everybody else their goods are now ore expensive for Americans to purchase resulting in fewer exports to the U.S. Good for our economy, not so good for theirs. Right now we need the global economy to rebound which means we need good monetary and fiscal policy around the globe. Dollar changes simply shift the growth from one country to another. Perhaps not the right solution.

Steve