January 13, 2023

For years the financial markets followed the rule, ”Don’t Fight the Fed”. When investors think the economy and inflation will behave one way but the Fed sees something different, the Fed will eventually win. Today that divergence of opinion is as wide as ever. The markets think that the peak in the funds rate is near and the Fed will begin to lower the funds rate in the second half of the year. The Fed says it does not plan to start easing until sometime in 2024. Who is right? In this case we think the Fed’s view of the economy and inflation is probably more accurate.

Using the fed funds rate futures contracts as a guide, investors believe that with two small 0.25% hikes in the funds rate by midyear, the economy will slow enough and inflation will subside with sufficient speed that the Fed will be in a position to cut the funds rate in the second half of the year.

For that to occur, the economy has to register very slow growth. Most economists anticipate GDP growth this year of about 1.0%. We concur. But the economy still has considerable momentum. Third quarter GDP growth was 3.2%. Fourth quarter appears to be solid at about 2.2%. GDP growth in 2023 should slip to the 1.0% mark but, thus far, the economy is showing few signs of a significant slowdown.

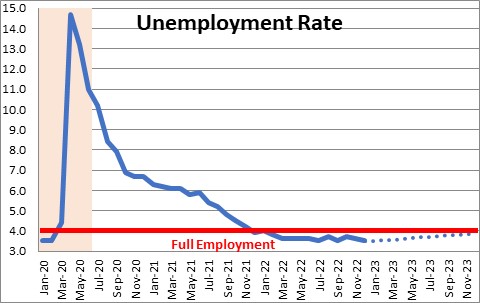

The real question is, what happens to the unemployment rate? The unemployment rate currently is 3.5%. The Fed believes the labor market is at full employment when the unemployment rate is 4.0%. At that point everybody who wants a job has one. The Fed also believes that slower wage growth is key to reducing inflation. It wants the unemployment rate to climb to 4.5% or so to make that happen. With projected GDP growth of 1.0% the yearend unemployment rate should be about 4.0%. That is not conducive to reduced wage pressures and a significant slowdown in inflation.

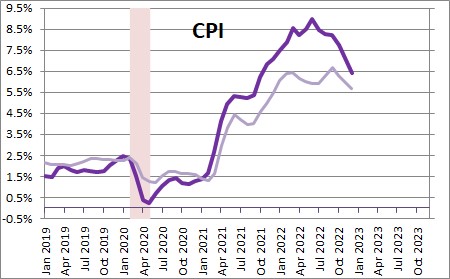

What about inflation? The overall inflation rate slowed in the second half of last year. The CPI reached a peak of 9.0% in June as the outbreak of war between Ukraine and Russia caused energy prices to soar. But as energy prices subsequently declined, the CPI slipped to 6.4%. That steady drop-off in inflation encouraged market participants that they were on the right track and that inflation might slow faster than the Fed was expecting. However, the slowdown was caused almost entirely by falling energy prices. The so-called “core” CPI, which excludes the volatile food and energy categories, peaked at 6.7% in September and ended the year at 5.7%. Furthermore, in the final three months of the year the core CPI climbed at a modest 3.1% pace which convinced the markets that the Fed tightening earlier in the year was working. But during that period of time the core CPI got a lot of help from sharp declines in both used car prices and airfares. For the core rate to continue to slow, these two categories must fall further. It is not clear that is going to happen.

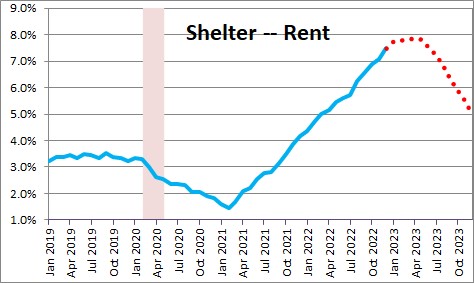

The most disquieting part of the core CPI is the shelter component, which rose 7.5% last year and in the final three months of the year climbed at an even faster pace. Because rents comprise one-third of the entire CPI index, it is hard to imagine how the overall CPI can fall to 2.0% when one-third of the index is rising at a 7.5% pace. If home prices continue to fall, rents will eventually slow — but with a lag of roughly one year.

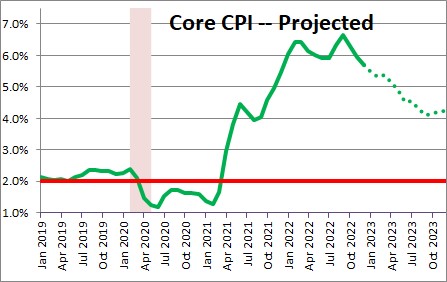

Putting all of this together, we expect the core CPI to rise 4.2% in 2023. Significant improvement in the core rate will not occur until very late in 2023.

The Fed plans to boost the funds rate to 5.1% in the first few months of this year. With a higher funds rate it believes GDP growth will slow to 0.5% for the year and the core inflation rate might subside to 3.5%. But if we are right that core inflation remains stubbornly high at 4.2% Fed officials will be disappointed. In that case it may raise the funds rate to 6.0% by the spring. The markets are not ready for that.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Hi Steve — Remember when the Fed guided they were never going to raise rates before 2024? Oops. Keeping in mind that the Fed still sees 25BP real funds as neutral, and 160 as tight, how long will they keep the funds rate at 5%, especially if unemployment sneaks over 4% in the coming months? We have our answer already — despite high inflation and low unemployment/high wage gains, they have decided to slow to 50 in Dec, 25 in Jan, back end has eased and financial conditions are back where they were in the spring. With your eco/inflation view, the Fed will be easing back and funds < 3% in a year's time is a better bet than 5%. I am not saying that's the correct policy, only the policy they will follow.