October 14, 2022

Recent data indicate that while consumer spending is slowing, employers are reluctant to lay off workers. Thus, GDP growth remains positive, but sluggish. At the same time the inflation rate remains at a 40-year high and is showing few signs of slipping – in part because of the reluctance of employers to reduce headcount. That creates a problem for the Fed. Its job right now is to reduce inflation to the 2.0% targeted pace. If the inflation rate does not soon begin to cooperate, the Fed may be forced to boost the funds rate far higher than is currently expected. It needs a positive real funds rate, which means that it needs the funds rate to be higher than the inflation rate. The core CPI is currently at 6.7%. We expect it to slow gradually to 4.3% by the end of next year. As long as that happens, the terminal funds rate of 5.0% seems appropriate. But if it slows less rapidly than expected the Fed will be forced to be even more aggressive in which case something will break and the economy will plunge into recession.

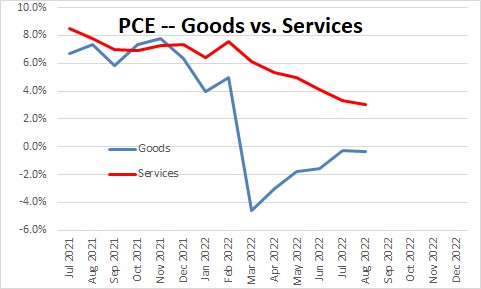

The retail sales data for September were about as expected. Consumers continue to spend, but their purchasing power has been countered by inflation. But the retail sales report only provides us with information about spending on goods which represent one-third of all consumer spending. Spending on services is much larger and represents the remaining two-thirds of the consumer spending pie. It is still climbing at a respectable pace. Specifically, in the past year consumer spending on goods has fallen 0.4%, spending on services has risen 3.0%. But these are year-over-year changes which can sometimes mask recent developments. In the past three months consumer spending on goods has fallen at a 0.9% pace. Spending on services has slipped to 1.8%. Consumer spending is slowing, but it is still growing.

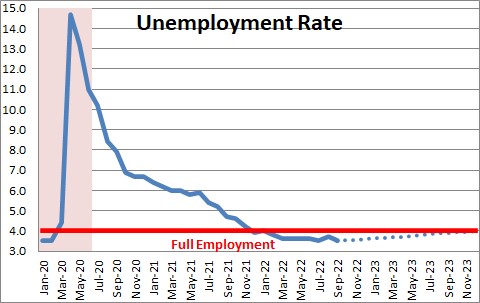

One of the reasons it has not slowed more sharply is because nobody is getting laid off. If workers lose jobs, income declines and consumers are forced to curtail spending. But the unemployment rate remains at 3.5% which is where it was prior to the recession. It is also below the 4.0% full employment level – which means that everybody who wants a job has one. Job openings have slowed but are still extremely high. As a result, nobody is worried about losing their job in the next six months. For that reason, consumer spending keeps chugging along at a moderate pace. Thus, jobs growth is ensuring that the pace of economic activity remains positive and the economy does not slip into recession.

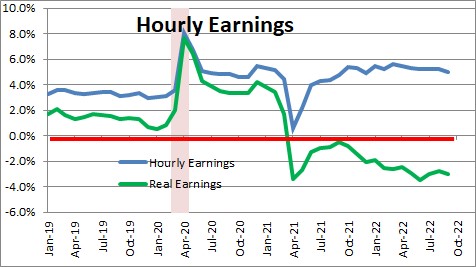

The problem with rapid jobs growth is that it keeps upward pressure on wages. In the past year average hourly earnings have risen 5.0% but inflation has risen by 8.0%. As a result, real earnings have fall by 3.0% during that period of time. This provides an incentive for individual workers and unions to push for even bigger wage hikes. To the extent that happens, firms will try to pass the higher labor costs through to their customers in the form of higher prices. This wage/price spiral is important because wages represent about two-third of a firm’s overall costs. If wages rise, prices are almost certain to go up. Thus far firms are finding little resistance to price hikes.

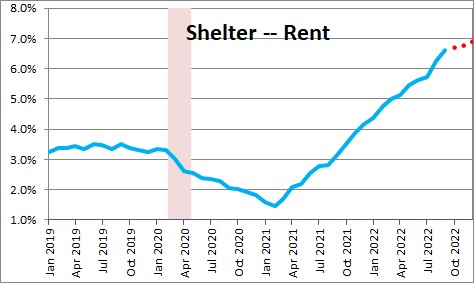

The housing sector is another important sector is determining the inflation outlook. The shelter component of the CPI consists largely of rents. But that chunk of the CPI has risen 6.6% in the past year which is the fastest 12-month increase on record for this particular component of the CPI. Shelter represents one-third of the entire index. How in the world can inflation return to 2.0% when one-third of the index is rising at a 6.6% pace?

All of this has important implications for Fed policy. The Fed knows that in a sustainable situation it needs to have the funds rate about 0.5% higher than the inflation rate. It believes that when inflation is 2.0%, the funds rate should be about 2.5%. Today the funds rate is in a range from 3.0-3.25%. In early November it will rise by 0.75% to 3.75-4.0%. In December it will almost certainly rise again, perhaps by 0.5% which will lift the funds rate to 4.5% by the end of this year. But inflation currently is 6.7%. it may slow but by yearend it is still likely to be 6.2%. If that is the case, a 4.5% funds rate at yearend will not do the trick. It will remain far below the level required to significantly slow the pace of economic activity, which is a necessary ingredient for a sharp drop in inflation.

We need employers to begin to lay off people and the unemployment rate to rise above the 4.0% mark. The longer it takes for that to happen, the more work there will be for the Fed to do. If the Fed should boost the funds rate to 5.0-6.0%, the risk there is a very real risk something will break and the financial markets will become the catalyst for a recession.

Stephen D. Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me