April 4, 2024

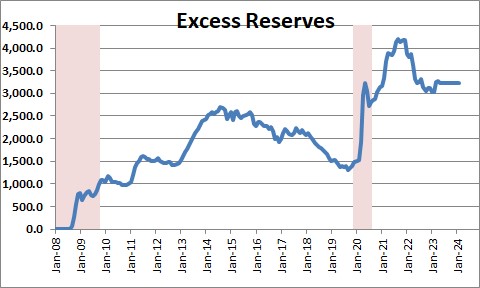

In the wake of the economic meltdown caused by the government’s dramatic measures to halt the spread of the corona virus the Fed leaped into action. It boosted its balance sheet by about $3.0 trillion in March and April 2020 primarily via purchases of U.S. government securities. It has since bought another $2.0 trillion of securities. When it purchases government securities the proceeds of the transaction are put into a bank’s “reserves” account at the Fed. Think of this as that bank’s checking account. Excess reserves in the banking system have jumped from $1.75 trillion in February 2020 to $4.2 trillion at the end of the year. It has since begin to decline and now stands at $3.3 trillion. This measures the ability of the banking system to make additional loans. Banks are still awash in funds just waiting to be lent to willing borrowers. The Fed needs to shrink excess reserves back to about $2.0 trillion.

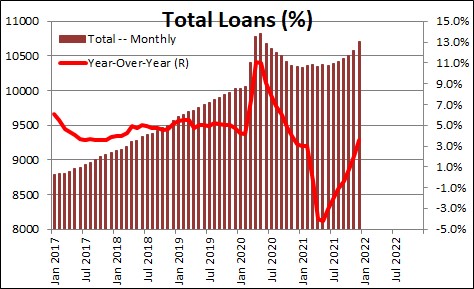

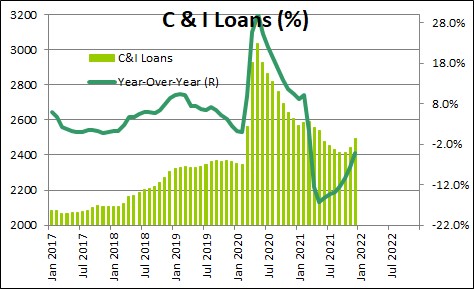

During the March/April 2020 recession bank loans soared largely because of growth in the commercial and industrial loans category.

Businesses wanted to be sure they had enough liquidity to stay afloat during the crisis. However, the recovery happened much more quickly than anticipated and with more vigor, so businesses did not need all the funds that they borrowed and C&I loans have fallen steadily until October of 2021 when they finally began to grow again.

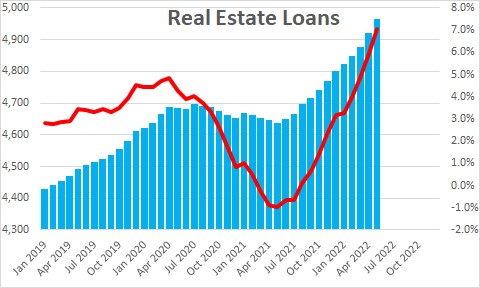

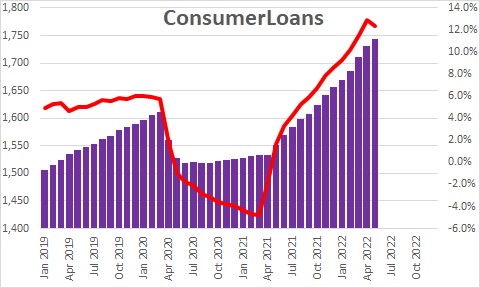

But since roughly the end of last year total loans have been growing. In this case the growth was primarily attributable to a combination of growth in mortgages followed by growth in the consumer loan category. In the past year real estate loans have risen at a 7.0% pace. Consumer lending has risen by 12.4%.

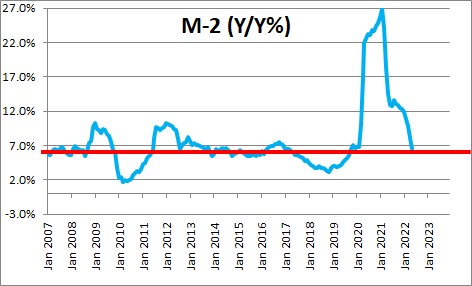

When banks lend to consumers and/pr businesses, they put the proceeds into a checking account. At that point the money supply begins to grow. In March 2020 M-2 grew at a 41.0% annual rate. In April 2020 it climbed by 76%. The Fed flooded the economy with liquidity in an effort to get it out of the deepest recession ever recorded. It worked. After declining 31% in the second quarter GDP growth surged in the third quarter by 34% and it has been growing fairly rapidly since, registering 5.5% growth in 2021 but it is going to register slower growth in 2022. M-2 growth has subsequently slowed and in the past year it M-2 has climbed by 6.5% Those are funds that businesses can use to pay their workers, pay the rent, and keep the lights on.

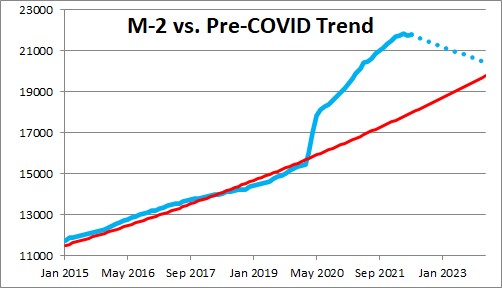

But with its purchases U.S. Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities in March and April 2020 and additional monthly purchases every month through the end of March 2022, the level of M-2 is far higher than it would have been had it grown at its steady trend rate of 6.0%. In fact, it is now $3.9 trillion higher than it should be. Those are funds slopping around in the economy that allow businesses and consumers to spend freely. Given that the economy is now at full employment, that additional spending is what is causing the inflation rate to rise quickly. Inflation will not decline significantly until the Fed shrinks the money supply back into line with long-term growth path. That process seems to have begun. In the past three months M-2 has growth at annual rates of 3.3%, -4.3%, and 1.3%. The problem is that even if M-2 shrinks at a 4.0% pace every month going forward, there will still be surplus liquidity in the system at the end of 2023. As long as M-2 remains above its trend line it will be hard to get inflation back to the 2.0% mark.

The point of all this is that, to its credit, the Federal Reserve stepped into the credit void to make sure that banks had adequate funds to lend to businesses to keep the economy functioning during the 2-month 2020 recession. But it should have begun to remove some of that surplus liquidity long ago. It has begin to become somewhat less accommodative but it will take a long time to eliminate that surplus liquidity.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, SC

Steve, absolutely fascinating. I just worry about my income and expenses and trust that the Feds know what they are doing. It appears that they do. Hope I am right.

Darrel Staat

Steve,

How will the Fed drain the reserves? If the Fed increased the reserved by buying securities, will they decrease the reserves by selling securities from their portfolio? I’m trying to square this with the statements that they’re going to just let the securities in their portfolio mature.

Also, if the Fed is trying to induce inflation, why do they want to neutralize the reserves by raising interest paid on them? Wouldn’t they want to have the banks start to utilize some of those reserves?

Is inflation caused by dumping more money into the system different somehow from (worse than?) inflation caused by a tighter labor market?

Always appreciate your insight.

-Pat

Hi again,

As you point out, the Fed does not intend to sell securities to drain those surplus reserves. But if it lets them mature and does not replace them it can get to the same place — it just takes a lot longer. Given the average maturity of its debt that would probably take about 10 years.

You are right again that the Fed would like to see a bit more inflation. And, in fact, that is probably what is happening right now. It seems like the underlying rate is beginning to pick up. The Fed would love to see the banks utilize some of those reserves by lending money to you and me and various businesses. But the banks are facing requirements to boost equity and, at the same time, every time we turn around they are subject to some new regulation. I think this Dodd Frank law, frankly, has gotten a bit out of hand. The other problem is that they need somebody willing to borrow. Right now consumers are borrowing, but very slowly. And corporations are not interested in investment so they haven’t been showing up on bank doorsteps looking for money. In addition to which they are holding a record amount of cash which they could use for investment if they were so inclined. Bottom line is, I don’t see anybody lining up to borrow. Banks can’t lend if nobody is on the other side.

Having said all this, in our economic nothing ever seems to happen gradually. Right now everybody, myself included, is expecting inflation to pick up gradually. But oil prices are no longer falling. Hence, one thing that has been holding down inflation has disappears. The dollar has stopped rising. When it was rising, imported goods prices were falling. That is not happening anymore. Wages have, at long last, begun to rise. Hence, in my mind, there is a risk that inflation could pick up next year faster than anybody expects. That would force the Fed to speed up the pace of tightening. Not my expectation — but probably more of a fear for me than the economy dropping out of bed.

Thanks for your note.

Steve

Thanks for all the commentary.

I’m still trying to understand why the Fed is paying interest (raising rates) on the reserves, particularly if there is not enough demand to borrow. Seems like the Fed is just wasting money in that case.

Thoughts on that?