February 16, 2023

Market participants have finally realized that seven rate cuts in 2024 were not going to happen. They now anticipate four. That seems far more reasonable. There is simply no reason for the Fed to rush. Fourth quarter GDP growth was robust at 3.3%. First quarter growth seems acceptable at somewhere around the 2.0% mark. The labor market is still cranking out about 160 thousand jobs per month. The employment rate remains at a 50-year low of 3.7%. Consumer sentiment is on the rise as it becomes increasingly evident that the Fed is poised to begin a protracted period of rate cuts by summer. Inflation should continue to shrink slowly but steadily throughout 2024 and 2025. Some economists seem to believe that the Fed needs to cut rates quickly and aggressively because interest rates are too high. We disagree strongly with that conclusion.

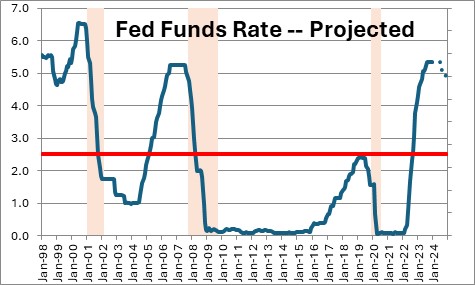

The federal funds rate has risen sharply in the past two years and appears high at 5.5%.

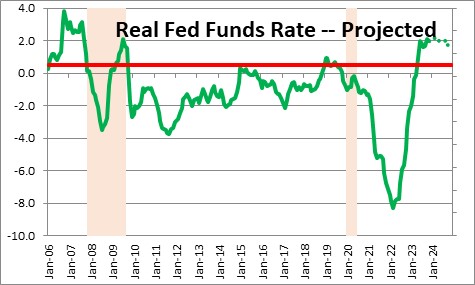

But that is not the appropriate way to determine whether a rate is too high. One needs to look at the “real” or inflation-adjusted funds rate. The Fed believes that the funds rate is “neutral” when it is 0.5%. Once the Fed achieves its 2.0% inflation target a funds rate 0.5% higher than that, or 2.5%, would be neutral. Today the funds rate is 5.5% and the core inflation rate is 3.9%. Thus, the “real” funds rate is 1.6%. Fed policy remains restrictive as it should be when the core inflation rate is almost double the Fed’s target.

But is a 1.6% “real” funds rate too high? We doubt it. The 1.6% real rate is clearly higher than it was prior to the 2020 recession when it was 0.5%. But that is not a fair comparison. That expansion ended not because interest rate were too high, but because of the pandemic and the policy-induced decision to shut down the economy for a couple of months. A real funds rate of 0.5% today would be too low. Going back to the earlier 2008-09 recession for comparison purposes the real rate peaked at about 3.0% which was high enough to push the economy into recession. Thus, in our opinion a real funds rate today of 0.5% would be too low, 3.0% would be too high. The current real funds rate of 1.6% seems about right.

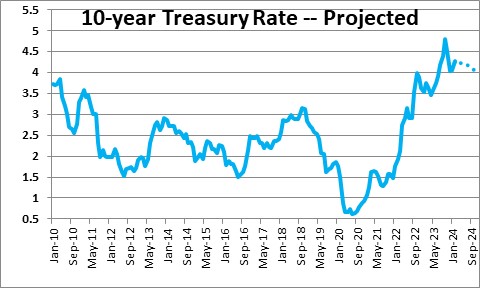

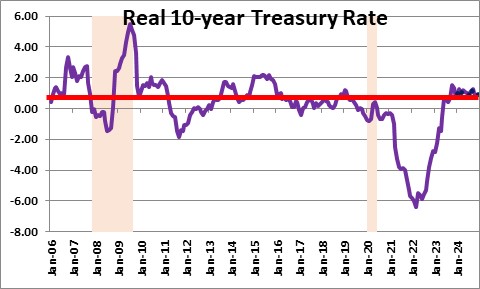

What about long-term interest rates? At 4.2% the 10-year Treasury note appears high by any recent standard. But that is in nominal terms. Like the funds rate, the proper way to determine whether that rate is too high is to look at it in “real” terms. When one does that, the picture changes dramatically.

Currently the 10-year note stands at 4.2%, the core inflation rate is 3.9%, thus the “real” yield on the 10-year is 0.3%. That rate is roughly in line with the average real rate for the 10-year period that ended in December 2019 – just prior to the 2020 recession. It is no longer the negative 6.0% rate that existed prior to the Fed starting its tightening initiative in 2022, nor should it be there. With a real rate roughly in line with its historical average it is hard to argue that long rates currently are too high.

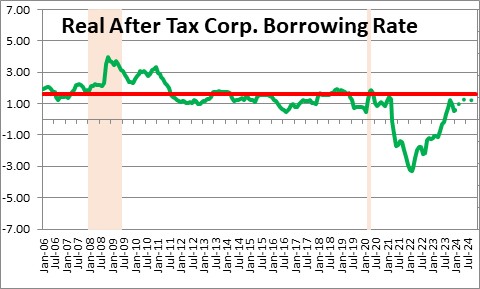

Finally, let’s look at interest rates from the viewpoint of a corporate treasurer. At the moment the yield on a Baa corporate bond is 5.7%. But the corporate tax rate is 21%. That means that after tax a corporate treasurer is not paying 5.7%, but 4.6%. With a positive inflation rate that corporate borrower is also able to pay back that loan with cheaper dollars. Given a borrowing rate of 5.7%, a corporate tax rate of 21%, and a 3.9% inflation rate, the real, after-tax cost of borrowing for a corporate Treasurer is 0.6%. In the 10-year period prior to the 2020 pandemic-induced recession, that real rate averaged 1.6%. Thus, the current 0.6% real, after-tax corporate borrowing rate is low relative to its long-term average.

From our perspective, real short- and long-term interest rates are roughly in line with where they should be. As long as the economy chugs along at a moderate pace and the inflation rate continues to shrink slowly but steadily, the Fed can take its time. We expect that an initial rate cut in July followed by two additional cuts in the fall would reduce the funds rate from 5.5% to 4.75% by yearend. But those would be the first in a series of rate reductions that will continue at least through the end of 2025.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me