May 10, 2024

.

.

The federal funds rate is the overnight rate that banks charge each other to borrow/lend reserves. Some banks have more reserves than they need. Others (principally large banks) are short of reserves and must borrow from other banks in the system, typically on an overnight basis. The rate at which this borrowing takes place is known as the fed funds rate. It is the only rate that the Fed can directly control. Most other short-term interest rates like Treasury bills, CD’s, commercial paper, etc. are very closely linked to this rate, so when the Fed tightens or eases all other short-term rates move in the same direction by essentially the same amount.

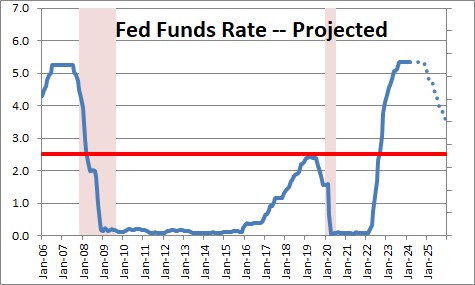

Once the recession began in December 2007 the Fed tried to stimulate the economy and ultimately pushed the funds rate almost to 0%. It remained at that record low level until December 2015.

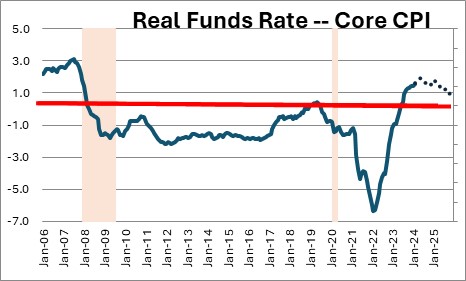

In December 2015 the Fed decided it was time to alter its policy and push the funds rate towards a more “neutral” policy stance. So what might be regarded as a “neutral” level for the funds rate? The answer lies in the relationship between the funds rate and the inflation rate. Whether an interest rate is high or low depends entirely on how it stacks up relative to the rate of inflation. Think of it this way. A 10% interest rate most of the time would be regarded as punishingly high. But in the late 1970’s when the inflation rate was 12%, a 10% rate was actually quite cheap. An investor could borrow at 10% for a year, buy an asset whose price would rise 12%, then pay back the 10% loan a year later and actually make money on the transaction. So whether rates are high or low really depends upon their relationship to the rate of inflation.

The difference between the funds rate and the inflation rate is known as the “real” funds rate. Over the past 30 years, the funds rate has averaged 0.5% higher than the inflation rate. So for years the Fed regarded a 0.5% “real” funds rate as relatively “neutral”. If the Fed wants an inflation rate of 2%, and believes that its policy is neutral when the funds rate was 0.5% higher than that, then the Fed regards a 2.5% funds rate as roughly “neutral”..

Today the funds rate is 5.5%. The core CPI is 3.8%. Doing the subtraction suggests that the “real” funds rate is +1.7%. Given that the Fed thinks +0.5% is a neutral “real” funds rate then, presumably, Fed policy is restrictive.

But if Fed policy is, indeed, restrictive. Why has GDP growth in the past year averaged 3.0%? Why is the core inflation rate still 3.8%. Going forward will the economy slow somewhat and the inflation rate slow? Or could the “neutral” real rate be higher than +0.5%. The reality is that nobody knows. The neutral “real” funds rate is unobservable.

Our sense is that GDP growth will slip from about 3.0% currently to 2.5% by yearend, and the core inflation rate will subside to 3.5%. That may be slow enough to get the Fed to reduce the funds rate by 0.25% by yearend to 5.25%. We also believe that the real funds rate may have climbed to 1.5%. Thus, the end point for the funds rate in nominal terms currently may now be 3.5%

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, SC

Follow Me