August 28, 2020

In what has been billed as a “landmark decision”, the Fed this week appears to have made sweeping changes in how it will conduct monetary policy. Basically, the Fed said it was now willing to tolerate inflation above its desired 2.0% pace as long as the economy had not yet achieved full employment. So what’s new? Fed Chair Powell told us that a long time ago. A discussion of what the Fed might do if inflation suddenly rises above target is interesting but useless. The problem is that inflation has fallen well below the Fed’s 2.0% target for years and is expected to continue to be below target for the foreseeable future. Our question is, if inflation has been below its target for years and the Fed truly wants inflation to average 2.0% for the cycle, how is it going to make that happen?

The Fed stated explicitly that it still wants inflation to average 2.0%. Powell pointed out that in a recession inflation might fall below its 2.0% target and that was okay. But if in the good times it remains below 2.0%, people would begin to expect the longer-run inflation rate to be less than 2.0%. If inflation expectations fall, then long-term interest rates will also fall, and if long rates decline then short rates also need to be lower. That means that in a crisis the Fed has less room to cut rates when the economy needs help. That makes perfect sense.

The Fed also said its primary focus is now on achieving full employment at which time the unemployment rate is about 4.0%. If the inflation rate rises above 2.0% before the economy achieves full employment, the Fed will not care. Achieve full employment first, then worry about the inflation rate.

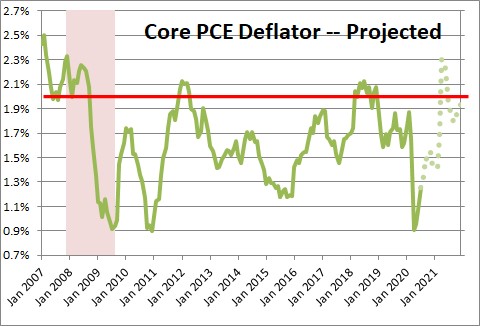

Speculating what might happen if the inflation rate climbs above 2.0% is an interesting discussion but it is, at this point, simply an academic one. The reality is that no one expects this situation to arise any time in the foreseeable future. In June the Fed said that by the end of 2022 it expected the core personal consumption expenditures deflator – the inflation measure it has chosen to target – to rise 1.7%. No one believes the inflation rate will climb significantly above the Fed’s 2.0% target for at least the next 2-1/2 years. Let’s not worry about that situation until we get there.

But yet the Fed still wants the core PCE to rise 2.0%. It has fallen short of that mark for years. Since 2008 this inflation measure has averaged 1.6%. This has been frustrating to the Fed. So how exactly is it going to get the inflation rate back above 2.0%?

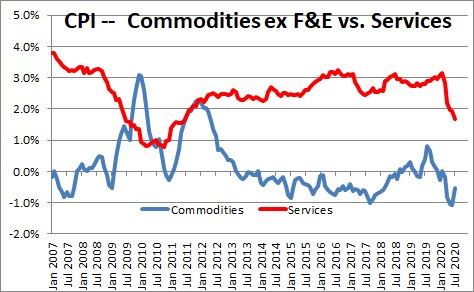

One of the big obstacles for achieving faster inflation is that the internet has essentially eliminated the ability of good-producing firms to raise prices. Whenever we purchase anything, we shop the internet first – Amazon in particular — and find the lowest price available. As a result, producers of goods in the U.S. have absolutely no pricing power. For example, take the CPI measure of inflation and split it between prices of goods versus services. In the past five years goods prices have consistent declined by about 1.0%. This is important because consumer spending on goods is 25% of GDP. Prices of services have risen by about 2.5%.

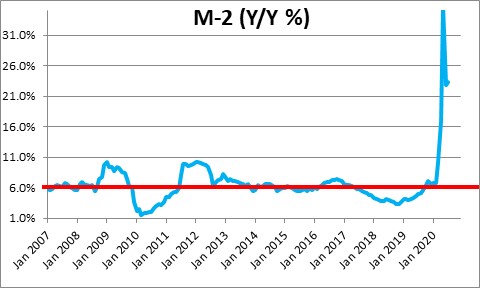

The Fed wants inflation to climb above the 2.0% mark. But if 25% of the economy cannot raise prices, how will the Fed boost the overall inflation rate? The answer seems to be to dramatically stimulate growth in the money supply. To make that happen the Fed needs to keep buying government securities. That is exactly what it has been doing since the downturn began in March and money supply growth has accelerated. Indeed, in the past six months M-2 has risen at a 37% annual rate. It needs to grow at about 6.0%. The Fed is hoping that if it continues to purchase government securities and the money supply keeps growing, eventually inflation will begin to climb. Unfortunately, the length of time between when the money supply begins to grow and when we actually see the inflation rate rise, is both long and variable.

We fully believe that while inflation is destined to quicken at some point, it is not exactly clear when that will happen. Once inflation does begin to climb, given the difference in the behavior of goods prices versus services it is difficult to see how it can start rising rapidly. For what it is worth, we expect the core PCE to reach 2.5% by the end of 2022 and the unemployment rate will have finally declined to its presumed full employment level of 4.0%. It is difficult to envision the Fed tightening with a 4.0% unemployment and a 2.5% inflation rate.

So why are we all speculating about how the Fed might respond to a situation that is unlikely to develop for at least 2-1/2 years? It seems like a rather ridiculous exercise to us. Nothing about monetary policy is going to change in the near term.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me