June 10, 2022

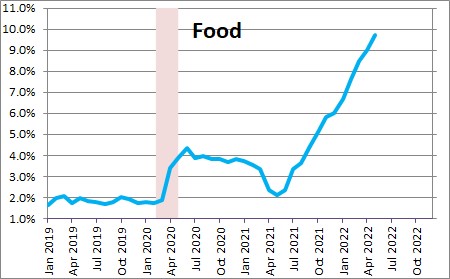

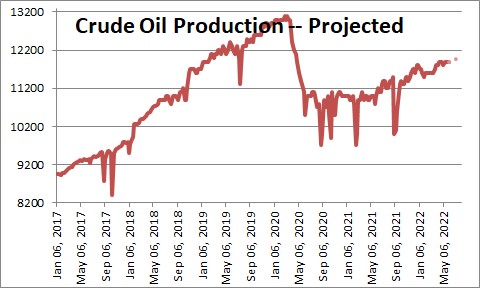

The Fed and economists like to exclude food and energy prices from their calculation of the underlying rate of inflation because they are quite volatile on a monthly basis. For example, a drought could boost food prices for several months, but they will return to normal once the next crop is harvested. A hurricane could curtail oil production in the Gulf of Mexico and cause energy prices to surge, but they will quickly retreat once the damage has been repaired and output is restored. On most occasions changes in food and energy prices can distort the picture of the underlying rate of inflation and it is correct to exclude them. But food prices have been rising for two years and have surged in recent months because Ukraine is a major exporter of wheat. It is safe to say that no corn or wheat will be exported from Ukraine for the foreseeable future. Furthermore, drought conditions in the crop-growing Western region of the U.S. have worsened significantly since the beginning of the year and hot dry summer weather conditions are on the way. With respect to energy, U.S. crude oil production remains far below its pre-recession level because producers are unwilling to invest in additional capacity given the Biden Administration’s declaration of war on the fossil fuel industry. Meanwhile, as the summer driving season gets underway and demand for gasoline increases, refiners are already running at full speed and lack the ability to significantly boost gasoline production. Eliminating food and energy prices from the calculation of the underlying rate of inflation was meant to cover fluctuations that might occur over a relatively short period of time. But today food and energy prices have been rising for two years and neither seems likely to reverse course any time soon. Excluding them from the calculation of the trend rate understates the dimensions of the inflation problem.

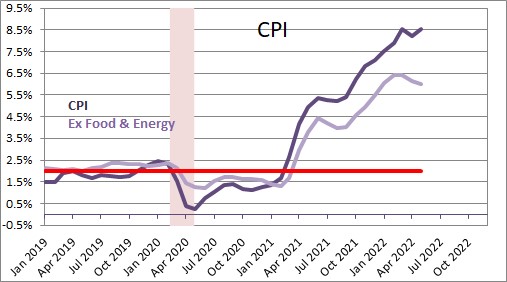

Currently, the overall CPI has risen 8.5%. Excluding food and energy products, the core rate of inflation has risen 6.0%. The Fed focuses on the core rate. But should it?

Food prices have risen 9.7% in the past 12 months. Food prices began to rise once the March/April 2020 recession ended. When war broke out between Ukraine and Russia food prices surged because Ukraine is a major exporter of both wheat and corn and the supply of those two commodities has been interrupted by the war. Once the war ends and Ukraine can plant more corn and wheat, the most recent price gains should be reversed. But, unfortunately, the war is unlikely to end for another year or more.

At the same time drought conditions in the West have worsened significantly since the beginning of the year according to the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. In the West 56% of the area is currently experiencing extreme (D3) or exceptional (D4) drought conditions. At the beginning of the year 30% of that region was experiencing those comparable drought levels. In California the comparable numbers are 71% today versus 17% at the beginning of the year.

Given the above, it is hard to see any set of circumstances that would cause food prices to decline sharply between now and the end of 2023.

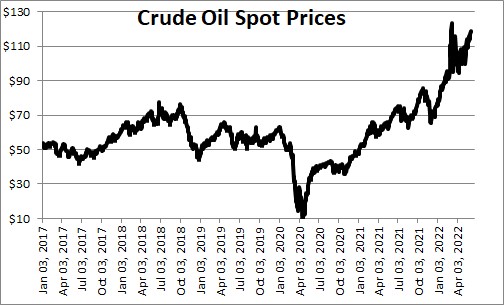

Crude oil prices have climbed to $120 per barrel. Part of the increase is attributable to a still relatively robust pace of economic activity. Part is due to the war.

But, more importantly, U.S. crude production of 11.9 million barrels per day remains about 10% below its pre-recession level of 13.1 mbpd. The EIA does not expect production to re-attain its pre-recession output until the end of 2023.

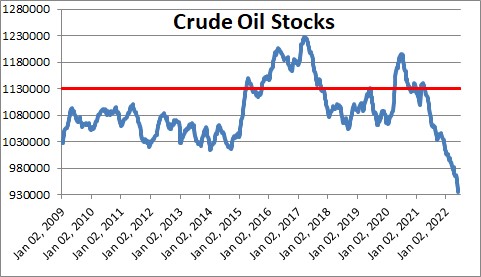

The subdued pace of production every month continues to fall short of demand. As a result, inventories of crude oil have fallen almost 20% below their long-term average.

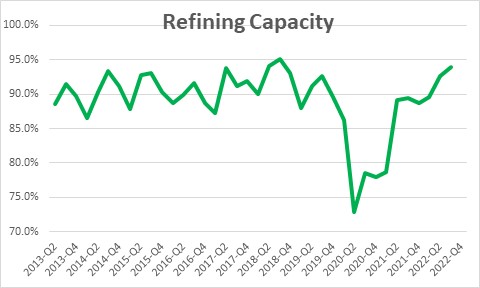

Gasoline prices have risen 20% in the past three months from $4.10 to $4.87 per gallon. The problem is that refineries are running at 94% of capacity which is a near-record high level. With the summer driving season just beginning and the demand for gasoline on the rise, oil refiners do not have the ability to significantly ramp up the pace of production.

Food and energy prices have been steadily rising for two years. If that is the case, there is little justification for excluding them from the calculation of the underlying or trend rate of inflation. The longer the inflation rate remains elevated the more entrenched inflation expectations become, and the more difficulty the Fed will have in getting inflation back to the 2.0% mark.

We think the Fed is understating the dimensions of the inflation problem by excluding what is happening with food and energy prices and focusing on the core rate which is currently less troublesome.

The Fed currently thinks it can get inflation back to 2.0% if it raises the funds rate to 2.8% by the end of next year. That is not even close to where it ultimately will need to go. Even if the overall CPI to abates to 6.2% next year and the core rate comes in at 5.6%, we should probably be thinking about the funds rate eventually reaching 6.5%. The Fed meets again this coming Wednesday. The peak funds rate is almost certain to be considerably higher than the 2.8% rate it indicated in March but will it be high enough? Not likely.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me