March 23, 2012

Fed Chairman Bernanke seems unwilling to acknowledge the considerable improvement in the labor market. Indeed, the Fed believes that the unemployment rate at yearend will be in a range from 8.2-8.5%. Given that it is currently at 8.3%, the Fed is basically saying that the unemployment rate will be unchanged during the next ten months. In contrast, we think the unemployment rate will decline to 7.6% by yearend. What accounts for such a wide discrepancy?

The difference seems to center on what has happened to the labor force in the past three years, and what is going to happen to the labor force between now and yearend. We care about the labor force because it plays an important role in determining the unemployment rate. If the labor force grows rapidly, the economy needs to produce a very large number of jobs to push the unemployment rate lower. If the labor force does not grow, then a very small number of new jobs will do the trick

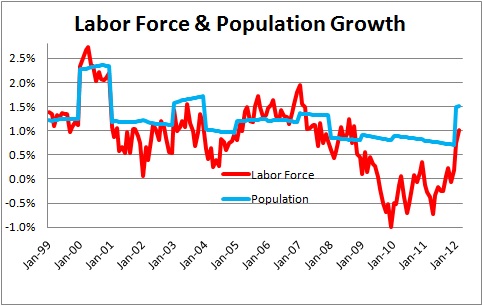

Typically, the population and the labor force grow in lockstep. From January 1999 through the end of 2008, the growth rates were virtually identical at 1.3%. But by early 2009 the economy was falling apart and labor force suddenly began to contract. Presumably, many unemployed workers became discouraged and gave up looking for a job. Once those people stopped looking for a job, they were no longer included in the labor force. If these labor force dropouts had continued to look for work and remained a part of the labor force, the unemployment rate would have been far higher. So now the question arises, what happens to these people given that the economy is doing better?

The Fed believes that as the economy gathers steam these people will become encouraged about their prospects of getting a job and will once again seek employment. This will cause a huge increase in the labor force. In the Fed’s world, the economy will be hard pressed to produce enough jobs to push the unemployment rate lower between now and yearend. We think that view is far too pessimistic.

In August of last year the unemployment rate stood at 9.1%. Six months later, in February, it had declined 0.8% to 8.3%. What happened?

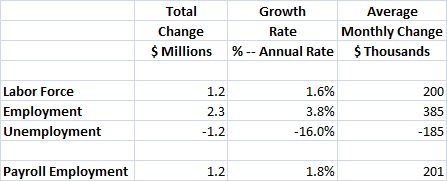

First of all, in that six month period of time the labor force grew at a 1.6% annual rate which is in sharp contrast to the steady declines registered since mid-2009. That works out to an average monthly increase of 200 thousand So, the Fed seems to be at least partially right — some of those folks who disappeared from the labor force over the course of the past couple of years are out looking again. But the second important point is that in that same six-month time frame jobs surged at a 3.8% pace. That works out to a monthly average increase of an astounding 385 thousand. This is where the Fed has it wrong. The economy was easily able to handle the additional job seekers and still manage to produce a decline in the unemployment rate of 0.8% in a very short period of time.

However, that monthly average increase in employment of 385 thousand stands in sharp contrast to the monthly average increase in payroll employment in that same period of time of just 201 thousand. How can those figures be reconciled? Basically, they are derived from two separate surveys.

For payroll employment the Bureau of Labor Statistics essentially asks employers to tell them how many people are on their payrolls every month. It then makes an allowance for small business employment based on historical trends, adds it all up, and out pops their estimate of payroll employment.

To calculate the unemployment rate the BLS does a monthly survey where its representatives knock on doors and basically ask two questions. “Are you employed?” If you say yes, you are officially employed and a member of the labor force. If you say no, the surveyor asks “Are you looking for work?” If you say yes you are officially both unemployed and a member of the labor force, and now have the somewhat dubious distinction of being incorporated in the unemployment statistics for that month. If you say no, you are not included in the labor force and, therefore, have no impact on the calculation of the unemployment rate.

The most important difference between the two surveys is that the payroll survey does not include self-employed workers because they are, obviously, not on a payroll. But they are included in the household survey. In today’s world many of the long-term unemployed, particularly older workers, realize that they have little chance of getting a traditional job so they start their own business. They are, therefore, included in the household survey of employment but are not included in the payroll measure.

But also in their estimate of payroll employment the BLS uses an estimate of small business hiring based on historical data. But because their recent data contains the recessionary period they are almost certainly going to underestimate payroll employment. It is primarily for this reason that we see consistent upward revisions to the previously published payroll employment statistics each month.

For these two reasons it is not too surprising that household employment has been rising on average 385 thousand during the past six months, while payroll employment has been climbing by just 201 thousand. Most economists believe that the more accurate portrayal of the jobs picture currently is provided by the household survey.

One final point worth noting is that the baby boomers are starting to retire. This group was born between 1946 and 1964. During that period of time there were 4 million babies born in each of 19 years, for a total of 76 million births. This means that 65 years later – or starting in 2011 — these people will begin to retire. Or, to put this in somewhat different terms, every day for the next 19 years the labor force will decline by 10 thousand workers as these folks retire. There is, therefore, no way that the labor force in the next ten years will grow at the 1.3% pace registered in the previous ten years. Most likely it will grow at half that pace, or perhaps 0.7%. If the labor force grows more slowly, the same number of jobs will allow the unemployment rate to fall fairly quickly – almost certainly far more quickly than what the Fed is currently expecting.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, SC

Follow Me