March 8, 2024

Every month employers have a choice. If demand remains solid they can either hire more workers, or work their existing employees longer hours. If in any given month economists know how many people are working and how many hours they worked, they can estimate how many goods and services they produced. In other words, they can get some idea of how GDP is shaping up in any quarter by examining the monthly employment and hours worked data. In February payroll employment rose 275 thousand which followed equally robust gains in December and January. With gains of that magnitude one would think that the economy is on a roll in the early part of 2024. But at the same time employers have been gradually cutting the hours worked by their existing employees. It appears that firms continue to add qualified workers whenever they can so that they will be better able to ramp up production later this year once the Fed begins to cut interest rates and demand accelerates. At the same time, they are trimming the number of hours worked so that — for the moment — total output stays in line with demand. The hours worked data suggest that GDP growth in the first quarter should be anemic. But there is another piece to the puzzle -– productivity growth. If each of those workers can become more efficient, GDP will grow far in excess of the hours worked. That has happened consistently in the past year. It appears to be continuing in the first quarter. And it should continue to happen for years to come. Maybe it is time to think about potential growth of 4.0% rather than 2.0%. We had it in the 1990’s. Why not now?

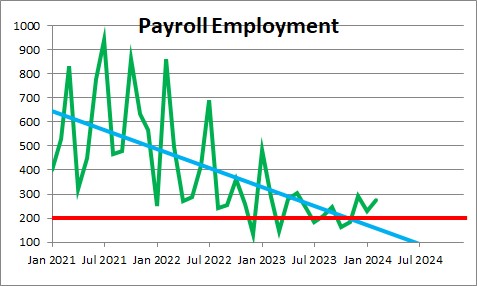

Payroll employment increased 275 thousand in February after having risen 290 thousand in December and 229 thousand in January. That means that in the past three months employment has risen on average 265 thousand per month. A year ago the comparable average monthly increase was 302 thousand. In other words, during a year when the Fed was steadily raising interest rates and everybody was expecting a recession, employers kept hiring vigorously. That seems counterintuitive, but because they have had difficulty finding an adequate number of workers for so long, they may feel compelled to boost the size of the workforce whenever a qualified worker becomes available. That behavior is a little bit odd, but perhaps explainable.

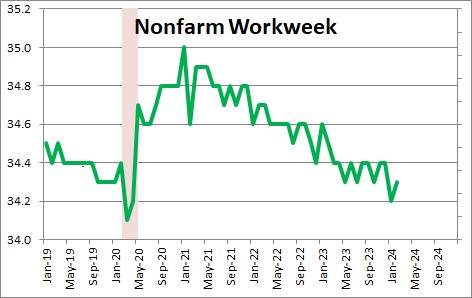

If firms kept all workers on the payroll working at maximum sustainable hours they would, presumably, crank out more goods than they actually need. So, while continuing to hire vigorously, they have simultaneously cut the number of hours each employee works. The workweek has been steadily shrinking for the past two years.

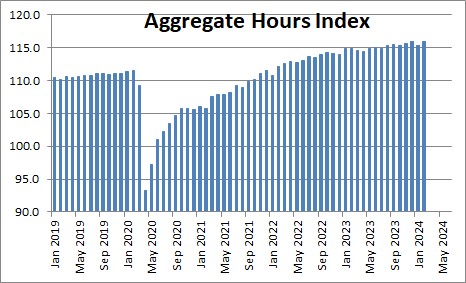

If one multiplies the number of workers by the length of the workweek, one can calculate the aggregate hours worked in any given month. That helps economists guesstimate what happens to GDP growth in that month. After rising sharply for the first couple of years after the recession, this index of hours worked has slowed considerably and, in fact, has risen just 1.0% in the past year.

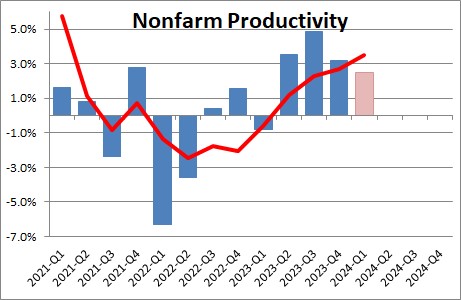

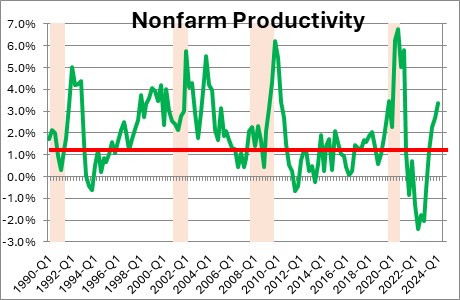

But there is still a missing piece to the puzzle. What if each of those workers were able to access the latest and greatest technology and were able to become significantly more productive? In that case, GDP growth would be far in excess of growth in the aggregate number of hours worked. And, in fact, that is exactly what has happened. In 2023 GDP rose 3.1% despite a relatively small increase in hours worked. Why? Because productivity climbed 2.7% in that year. And, given what we think we know about the first quarter, the yearly productivity gain may soon approach 3.5%. To put that in context, in the past ten years productivity has risen on average 1.2% annually. A 3.5% increase in a year is huge!

Why should productivity accelerate so dramatically? Tech spending grew at a double-digit pace in 2021 and 2022. As demand continued to grow but firms could not find enough bodies to hire, they presumably spent some money on technology to make their existing employees more productive. It is working. Workers are able to work wherever they want and no longer have to commute long distances into big cities on a daily basis. Happy workers tend to be more productive. And now firms in virtually every industry are finding ways to embrace artificial intelligence to cut costs. These recent developments are similar to the productivity surge that occurred in the 1990’s as the internet was being adopted. At that time productivity continued to grow rapidly for a decade.

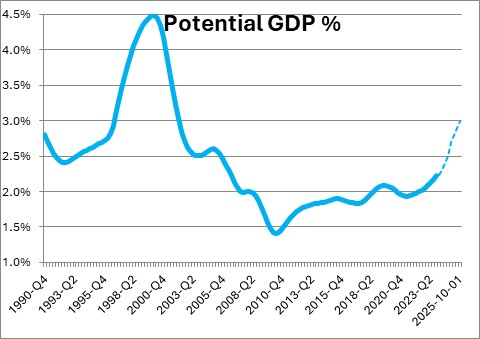

Faster growth in productivity implies a much faster potential growth rate for the U.S. economy. Currently, potential growth (basically our economic speed limit and growth in our standard of living) is estimated to be about 2.0%. That growth rate consists of 0.6% growth in the labor force combined with 1.4% growth in productivity. But what if, going forward, productivity growth accelerates to 3.5%? Now the same calculation suggests a potential growth rate in the U.S. economy of about 4.0%. Given what happened in the 1990’s that does not seem too far-fetched.

If the economy can grow at 4.0% rather than 2.0%, the stock market no longer seems over-valued. Income will grow far more quickly which will make it easier for consumers to spend and save. The economy can grow at a 4.0% pace without giving rise to a pickup in the inflation rate. Best yet, potential GDP growth is a proxy for growth in our standard of living. Growth of 4.0% sounds a whole lot better than 2.0%.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Stephen, thanks again for your keen insight into what may appear to be a confusing economic situation that we find ourselves in. Always, when one gain perspective, what seems messy, becomes understandable and clear.

Thanks for letting us walk around in your mind. It is most helpful.

Darrel

Hi Darrel.

Thanks for your kind note, as always, I never thought of anybody having the opportunity to walk around in my mind. Nice phrase! I love it!

Steve