April 8, 2016

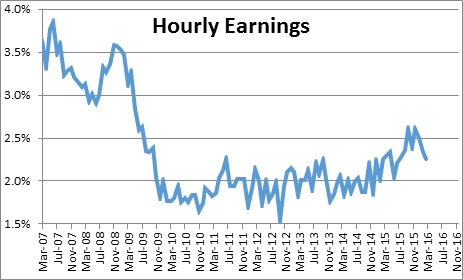

Many economists fret about the slow growth of average hourly earnings. It has been climbing at about a 2.0% pace versus about 3.5% prior to the recession, but three factors suggest wage growth is not only faster than it appears, it is more than adequate.

- Recent hourly earnings growth has been biased downwards by shifts into and out of the labor force.

- Labor costs adjusted for changes in productivity have been rising faster than their historical average which will soon put upward pressure on the inflation rate.

- With inflation rising slowly, real compensation is growing more rapidly than usual.

Prior to the recession hourly earnings were climbing at about a 3.5% pace. Since the recession ended growth has slowed to about 2.0%. Fed Chair Yellen highlights this slow growth and concludes that the labor market is not yet close to full employment. If it were close to full employment earnings growth should accelerate.

But economist Mary Daly at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco suggests that aggregate earnings growth has been distorted by movements of workers into and out of the labor force.

For example, during the recession she notes that aggregate wage measures were propped up by the disproportionate firing of low-wage workers. As those workers left the labor market, “the mix of employees who remained on the payroll generally had higher-than-average skills and wages which boosted the average aggregate wage.” As the labor market improved many of those workers on the sidelines or holding part time positions have moved back into the labor market. “The vast majority of these workers earn less than the typical full-time employee, so their entry pushes down the average wage.”

Ms. Daly also notes that as baby boomers retire “The exit from full-time employment of older, higher-paid retirees has pushed down wage growth. Furthermore, with so many of this generation still to retire, the so-called Silver Tsunami will be a drag on aggregate wage growth for some time.”

She concludes that sluggish wage growth may be a poor indicator of labor market slack and, in fact, after adjustment for compositional changes wage growth is consistent with a strong labor market that is drawing low wage workers into full time employment.

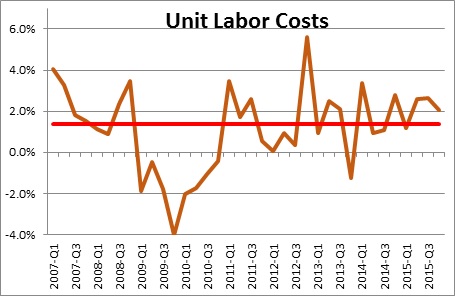

Second, if these low wage workers entering the labor force are less productive, unit labor costs will climb which will put upward pressure on the inflation rate. If your employer pays you 2.5% higher wages but you are more efficient and produce 2.5% more output, it does not matter. But if your boss pays you 2.5% higher wages and you are not more productive, that is a problem. It will force the firm either to accept reduced profit margins, cut non-labor costs, or pass through the higher labor costs to the firm’s customers in the form of higher prices. Labor costs adjusted for changes in productivity are called “unit labor costs”. As productivity growth began to slow in 2010, unit labor costs began to rise, and for the past couple of years have been climbing at a 2.0% pace which is faster than the average 1.4% average increase during the past 25 years. Thus far the increase in unit labor costs has been countered by falling commodity prices, oil in particular, which has mitigated the need for higher prices. But as commodity prices stabilize the rising labor costs are increasingly likely to boost the inflation rate.

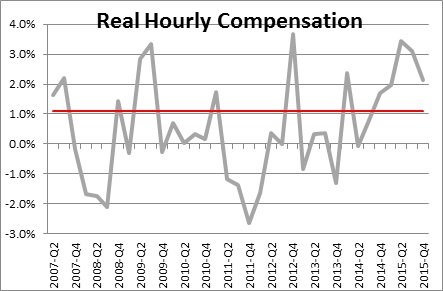

Finally, keep in mind that even if one accepts the wage data at face value, with little inflation real hourly compensation is climbing at a 2.0% pace which is well in excess of its 1.1% historical average. Thus, the supposedly meager wage games are still producing a faster than normal increase in purchasing power.

While most economists are distressed by a seemingly slow rate of wage growth we are less disturbed. Adjusted for changes in the composition of the labor force wage growth is about what one might expect. Furthermore the wage gains have not been matched by a commensurate increase in productivity. Thus, workers cannot justify faster wage growth. Finally, because inflation is so low the current pace of wage inflation is lifting worker purchasing power faster than the norm. Using slow wage growth as an indicator that the labor market is not yet at full employment is unwarranted.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, SC

Follow Me