August 25, 2023

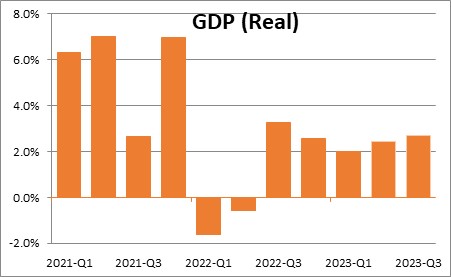

How high must the funds rate go before the Fed says it is done tightening? When might the Fed begin to lower the funds rate? Fed Chair Powell refuses to answer either of those questions for two good reasons. First, the Fed never wants to be locked into a particular position because the incoming data might not cooperate and the Fed would be forced to backtrack. Second, neither Fed Chair Powell nor his colleagues know the answers. Economists are all guessing. Powell has said that he thinks the funds rate is close to the peak which seems to make sense. After all, the Fed has raised the funds rate from 0% to 5.5% already. Surely the peak cannot be far distant. The market seems to agree and believes that the Fed may raise the funds rate one more time by yearend to 5.75%. But keep in mind that in the past four quarters GDP growth has averaged 2.6%. We believe that third quarter GDP growth will be 2.7% and other economists have guesstimates in the 4.0-5.0% range. The increase in rates thus far has not slowed GDP growth at all. Will the lagged impact from earlier rate hikes and one additional increase in the funds rate do the trick? There are legitimate reasons to believe that growth will slow in the quarters ahead, but we have heard this story before. Just a few months ago economists thought that the economy would slip into recession in the second half of this year and that the Fed would cut the funds rate by yearend. Not even close.

The Fed seems to gauge whether its policy is tight by examining the real or inflation-adjusted funds rate. It believes that in the longer run the funds rate will be about 2.5%. At the same time it targets the inflation rate at 2.0%. That means that implicitly it believes that a neutral real funds rate is +0.5%. Today with the funds rate at 5.5% and the year-over-year increase in the core CPI of 4.7% the real funds rate is +0.8% which is barely into restrictive mode.

Powell is not a great fan of this concept for two reasons. First, it is unobservable. The funds rate is known, but is the correct inflation measure the CPI, the core CPI, the core personal consumption expenditures deflator, or something else? The Fed happens to use the core PCE deflator which is currently 4.1%. Thus, in the Fed’s world the real funds rate today is +1.4% which it regards as “restrictive” versus the +0.8% that we believe given a different measure of inflation. So is Fed policy today restrictive, or not? It depends.

The other problem is that a neutral real funds rate seems to change over time. Since 1980 the peak real funds rate has been gradually falling. When inflation was well-entrenched in the early 1980’s the Fed needed to boost the real funds rate to the +8.0% mark to slow the pace of economic activity. In subsequent cycles the peak real funds rate was between 3.0-5.0%. The real funds rate was slightly positive in 2020 when the economy fell over the edge into recession. But that was not because interest rates were too high. It was whacked by the pandemic. So is the Fed right that a real funds rate today of +0.5% is neutral? Seems a bit low to us.

There is one other peculiar characteristic of the real funds rate – the real funds rate will climb if the inflation rate slows. For example, we noted earlier that with the funds rate today at 5.5% and the year-over-year increase in the core CPI at 4.7%, the real funds rate is +0.8%. But we also believe that by the end of the first quarter the core CPI will have slipped to 3.8%. If the Fed leaves the funds rate at 5.5% the real funds rate at the end of March will have climbed to 1.7% without the Fed raising rates further. Is that high enough to slow the economy?

In the past year real GDP growth has averaged 2.6%. We believe that GDP growth in the third quarter will be 2.7% and some economists are predicting GDP growth this quarter in the 4.0-5.0% range. So where’s the slowdown? All of this suggests to us that, thus far, interest rates have not risen high enough to work their magic and slow the pace of economic activity.

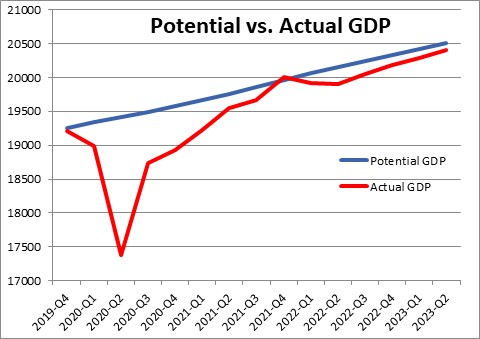

All of this matters because the economy has virtually no remaining slack. In the second quarter the level of GDP is within an eyelash of the Congressional Budget Office’s estimate of potential GDP. If GDP grows as rapidly as we and others expect in the third quarter any remaining slack in the economy will disappear completely. The Fed needs GDP growth to slow to its potential pace of 1.8% to have any hope of quickly achieving a 2.0% inflation rate.

The Fed meets next on September 19-20. The widespread expectation is that the Fed will leave the funds rate at 5.5%. But if third quarter GDP growth is as robust as it seems at the moment with a possible growth rate of 2.7% or faster, and the core CPI for August comes in at 4.5% which is still more than double the Fed’s desired pace, how can the Fed not raise the funds rate? If the economy were showing some sign of slowing down they might be able to get away with leaving the funds rate unchanged. But if the economy is charging ahead, no action on its part would give the appearance of capitulating in its battle to fight inflation. Image is important. Furthermore, what if the neutral funds rate today is not the +0.5% that the Fed expects currently but, say, 3.0%? In that case Fed policy is not yet in the ballpark with where it needs to be.

We continue to look (and hope) for more widespread signs of the economy slowing down. Thus far, those signs are elusive.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me