February 26, 2021

For the first time in a long while bond market participants are concerned about inflation rising as the result of a combination of factors. The economy already has a head of steam with about 8.0% GDP growth expected in the first quarter. The government is poised to add more fuel to the fire via another round of fiscal stimulus. The end of the pandemic is in sight. And the money supply is growing at a breakneck 26% pace. Thus, the fear of inflation has already begun to rise. How long until actual inflation begins to climb? If inflation accelerates, what will happen to bond yields?

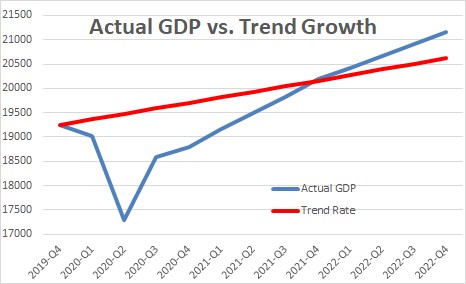

Earlier this month we learned that retail sales surprisingly rose 5.3% in January. Economists re-did their calculations of first quarter GDP growth and revised them upwards sharply. We now anticipate GDP growth of 8.2% in the first quarter. The economy is starting 2021 with a bang.

Then, there is a $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief package working its way through Congress with a further infrastructure spending bill in the works later in the year. All of this additional government spending will further stimulate the economy.

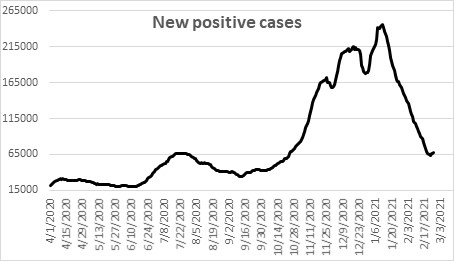

For the first time in a year the end of the pandemic is in sight. The number of new cases daily has declined from a peak of 245 thousand per day in mid-January to 65 thousand by mid-February. Indeed, some epidemiologists now believe that the U.S. can achieve herd immunity by the end of April. Once people become convinced that the virus is under control, they will once again feel comfortable going to restaurants, traveling, staying in hotels, and going to sporting events.

Given all of these factors we anticipate GDP growth of 7.5% for the year. if that happens any remaining slack in the economy will disappear by yearend.

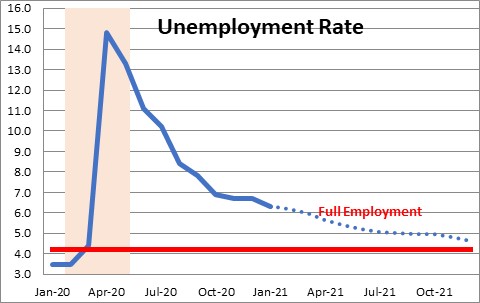

At the same time, the unemployment rate will have declined from its current level of 6.3% to its full employment threshold of 4.0% by yearend. Restaurants, bars, hotels and airlines will rehire staff. Manufacturing and constructions firms may finally find some of the skilled workers they are seeking.

Once the economy reaches full employment, the economy will be in danger of overheating. We believe that will occur by the end of this year — two years ahead of the Fed’s schedule. At that point, inflation may begin to climb.

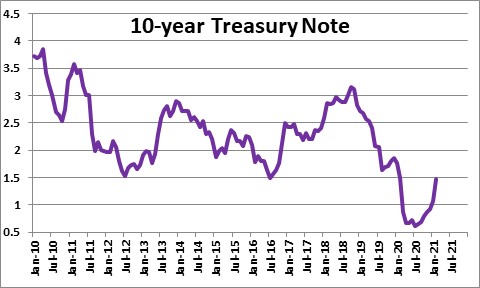

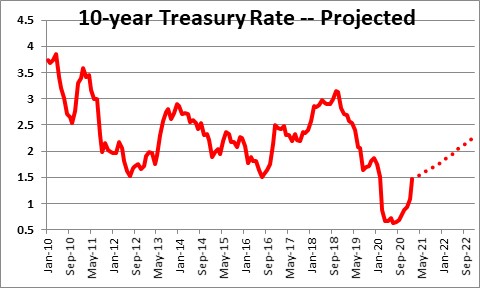

Now, back to the Treasury market. The yield on the 10-year note was 0.6% last summer. It is 1.5% today. That is an increase of 0.9 percentage point in six months. Clearly, the market has begun to anticipate an increase in the inflation rate and, perhaps, the volume of Treasury securities that will need to be issued to finance yet another record-shattering budget deficit.

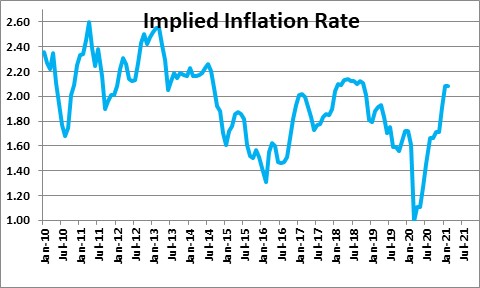

One can track inflation expectations by looking at the difference in yield between the 10-year note and its inflation-adjusted equivalent. The implied inflation rate began to rise about this time last year from a low of 1.0% to 2.1% today.

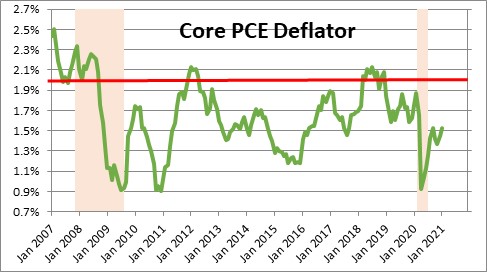

Thus, inflation expectations have risen, but actual inflation has not followed suit. The core personal consumption expenditures deflator (excluding the volatile food and energy components) rose 1.5% in 2020 which is 0.5% lower than the Fed’s 2.0% inflation target. Indeed, this inflation measure has been averaging 0.5% below target for the past decade. So while inflation expectations have been on the rise, actual inflation remains anemic. But that may not last much longer.

While consumer inflation remains slow at the moment, asset prices are skyrocketing. Stock prices, home prices, commodity prices, and even Bitcoin are surging as investors seek higher returns. That is a sign that there is too much credit available.

Inflation has remained in check largely because of the extremely deep recession last year. The unemployment rate surged to 14.7%. GDP fell far below its potential path. The economy has partially recovered, and if it grows at the 7.5% pace we expect this year, the unemployment rate should approach the 4.0% full employment threshold by the end of this year and, GDP should get back to its potential growth path. The economy will be at full employment. It is at that point that inflation should begin to rise. To get the workers they need employers will have to bid them away from other firms by offering higher wages and/or more attractive benefits. They may be able to raise prices because the demand for their goods is so strong.

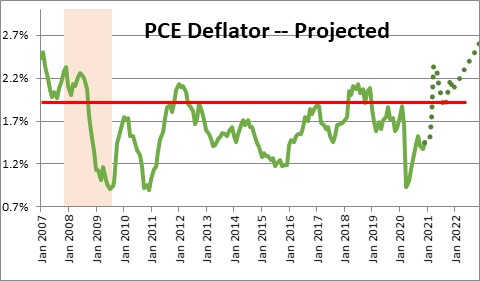

For all of these reasons we believe that the PCE deflator will accelerate to 2.1% this year and 2.6% in 2021.

What does all this imply for 10-year note yields for the rest of this year and 2022? Today the 10-year yields 1.4%. We believe that the yield on the 10-year will be 1.8% at the end of this year and 2.25% at the end of next year.

Why so low? In the past 10 years the yield on the 10-year has averaged about 0.5% higher than the inflation rate. If at the end of next year inflation is 2.6% why shouldn’t the 10-year reach 3.1%? Easy. The Fed won’t let that happen for two reasons.

First, if the 10-year note climbs from 1.5% today to 3.1% at the end of next year it would likely run the risk of dumping the economy back into recession. A 3.1% rate would be the highest rate in a decade. The Fed is not going to let that happen. It will buy whatever amount of Treasury securities is required to prevent long rates from spiraling out of control.

Second, if the Fed allows long-term interest rates to rise sharply or, worse yet, if the Fed were to tighten, the interest cost to the Treasury would rise dramatically. Not a good idea when it has just incurred back-to-back budget deficits in excess of $3.0 trillion.

The bottom line is that inflation is going to rise. Long-term interest rates are going to climb. And the Fed is not going to tighten any time in the foreseeable future.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Steve,

Is this the time to consider raising taxes? It seems like that’s a lever to be considered? The spending is baked in and I agree that the economy is overheating. Thoughtful taxation of specific areas to slow things down a bit would help with the deficit and might slow economy a bit in 2022 and beyond? What are your thoughts?

Also, what do you think the effect of the rest of the world’s deficit spending might have on long term U.S. rates? Given the massive deficits, I do think the Fed will want to keep rates as low as possible for as long as possible. Are we going to be able to leverage our status as the worlds reserve currency to buy us some points downward on the long term rates? I am very concerned about the deficit, especially once rates begin to rise.

Hi Chris,

Like you I am concerned about the size of budget deficits and debt going forward. Raising taxes is an option at some point. But not now. With the unemployment rate still at 6.3% and still some slack in the economy (i.e., actual GDP below potential) I am not sure this is the time. Even if someone were inclined to believe this is the time to raise taxes, there isn’t anybody in Congress that would allow that to happen. They are all in a spending free for all to jack up the pace of economic activity to get back to full employment. And it won’t happen in 2022 either with an election in November of that year. 2023 perhaps?

Steve

Hi Steve,

You’re probably right. Unless something happens in the first 100 days, it’s unlikely to happen later on. Even for my admittedly liberal sensibilities Warren’s 6% tax on billionaires seems like a bad idea and I’m not aware of anything else on the horizon.

Best,

Chris