May 14, 2021

In April inflation returned in spades and the markets did not like it. The stock market plunged. Consumer sentiment fell 5.5 points in May as consumers were shaken by the monthly jump in inflation. Some of the upswing reflects rebounding airfares, hotel room rates, and restaurant prices which fell sharply during the recession. Some of the increase reflects supply interruptions which have curtailed the supply of some products and pushed prices higher. Those factors are likely to be temporary. But some of it also reflects a shortage of qualified, willing workers. Firms of all types and sizes are scrambling to find the bodies they need. They are raising wages and offering bonuses to attract workers. Their higher costs will inevitably flow through to their customers. Or will they? Is it possible that faster growth in productivity can short-circuit some of this pass through? While inflation is certain to rise, the markets may fear a more dramatic increase than is likely to be the case.

The smaller-than-expected increase in payroll employment in April of 266 thousand, despite an unemployment rate which remains high at 6.1% and a record number of job openings, highlights the difficulty being faced by employers of all types. Many respondents to the monthly purchasing managers’ reports for both manufacturing and service sector firms cite their inability to hire an adequate number of workers. So what is going on?

Many relatively low paid workers in the food and beverage industry and in retail shops may be re-thinking their options. Do they want to continue working in a low-paying job in a restaurant or bar or retail shop forever? Some have already found employment elsewhere. Others are undoubtedly looking. That is a relatively easy decision to make if someone is paying you while you contemplate your future. But once that is no longer the case, presumably once Federal unemployment benefits expire after Labor Day, reality sets in and a large number of those workers will go back to work. In that event, the labor shortfall may become less acute by the fall. But what if it is not the case and those workers are determined to seek employment in a higher paying industry?

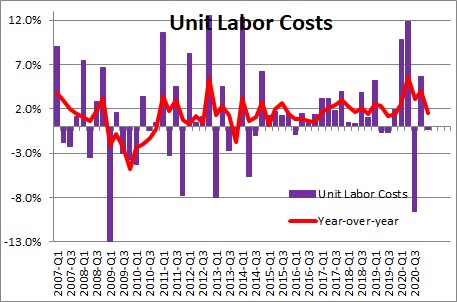

Firms of all sorts are already raising wages and offering bonuses to attract the workers they need which increases their labor costs and, presumably, translates into higher prices and a faster inflation rate. However, higher wages do not necessarily translate into higher prices if they are offset by commensurate gains in productivity. What we should be following is unit labor costs which are labor costs adjusted for the change in productivity. Think of it this way. If I pay you 5% higher wages my labor costs have risen and I might be tempted to raise prices to offset it. But what if you are 5% more productive? I do not care. I am getting 5% more output. In that case, unit labor costs – labor costs adjusted for the change in productivity is 0%. I would have no reason to raise prices despite your increased wages.

In the past decade unit labor costs have risen 1.5% — a 2.5% increase in compensation partly offset by a 1.0% increase in productivity.

That 1.5% increase in unit labor costs was matched by a 1.5% average inflation rate.

But now let’s suppose that the tight labor market causes wages to accelerate from 2.5% to 3.5%. If productivity remains steady at 1.0%, then unit labor costs would climb by 2.5% (3.5% increase in wages offset by 1.0% productivity) and, most likely, the inflation rate would accelerate by a percentage to 2.5%. But what if businesses could boost productivity from 1.0% to 2.0%? In that case unit labor costs would not increase at all (a 3.5% increase in compensation partially offset by 2.0% growth in productivity). Unit labor costs remain at 1.5% and the inflation rate would, presumably, remain steady at about 1.5%.

How likely is it that, going forward, we are going to see productivity accelerate? Actually, quite likely. Technology helped the economy emerge from the recession. Think about retail. Consumers had to buy goods on line during the recession. Retail shops across the country were closed for months. Retail firms that already had an on line presence or were able to develop one quickly survived. Think Amazon, Walmart, Target. Many others that were unable or slow to adapt did not make it. Then think about doctors’ offices and the shift to Tele-health. Think about restaurants. Ones who were able to develop a takeout business using UberEats or Grubhub survived when in-restaurant dining was prohibited. Ones who did not avail themselves of this technology quickly ran out of cash and many did not make it.

For the decade prior to the recession productivity rose by 1.0%. In the four quarters of last year and first quarter of this year productivity has risen at a 4.0% pace. Some of that was expected because when the economy dips into recession the least productive workers are let go first. But, in this case, there was a strong incentive for firms to turn to technology to help them adapt to this changing economic environment. Is it unrealistic to think about productivity growth climbing from its decade-long average of 1.0% to 2.0%? We do not think so, but only time will tell.

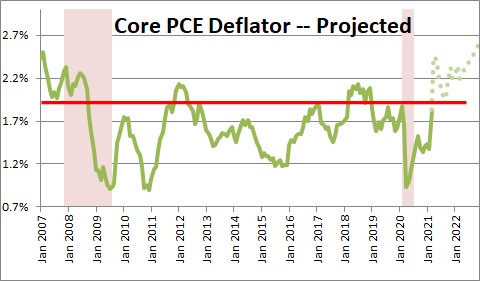

Inflation is on the rise. Growth on the demand side of the economy is exceeding the economy’s ability to produce. That is a recipe for higher inflation. Money supply growth has skyrocketed to 24%. Consumers have ample liquid funds to spend. The sharp jump in the CPI in April is a wake-up call that inflation has begun to climb. But consumers and the markets may have overreacted and fear a runup in inflation that is in excess of what we may actually see. For what it is worth, the core CPI increased 1.6% last year. We expect that core rate to climb to 3.4% this year and rise by an additional 3.4% by the end of next year. A faster rate of inflation to be sure, but probably not enough to force the Fed to raise rates any time soon. To a large extent, the longer-term runup in inflation will depend upon gains in productivity which, in the early going, seems to be accelerating. That is a good thing.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me