March 2, 2018

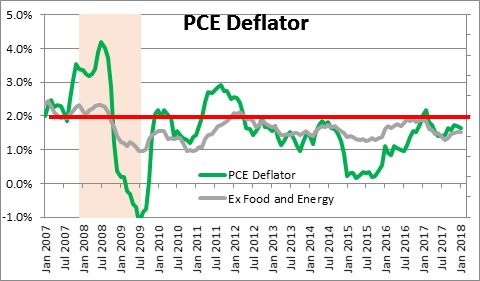

The Fed has embarked on a course of very slow and gradual increases in interest rates over the past two years designed to bring the funds rate into closer alignment with its historical average. It has been able to proceed slowly because the inflation rate has remained well below the Fed’s 2.0% objective. Specifically, the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation, the personal consumption expenditures deflator excluding food and energy, has risen 1.5% in the past year. Given the apparent tightness in the labor market that is less than what the Fed and most private sector economists had anticipated. In his first appearance before Congress, Fed Chairman Powell acknowledged that the Fed’s understanding of the forces currently driving inflation is imperfect. If the Fed can better understand its recent behavior, it will be better able to predict the likely path of inflation in years ahead.

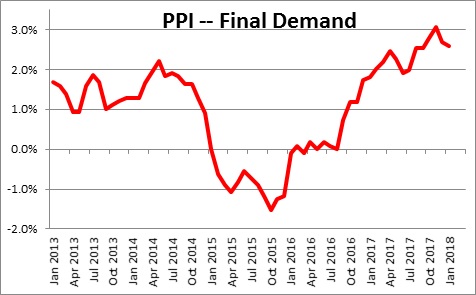

First, Powell indicated that much of the shortfall in inflation is readily explainable. The decline in commodity prices from mid-2014 through the end of 2015 helped to keep inflation in check for a protracted period, but such prices have been on the upswing since mid-2016. Thus, the downward bias from falling commodity prices should be temporary.

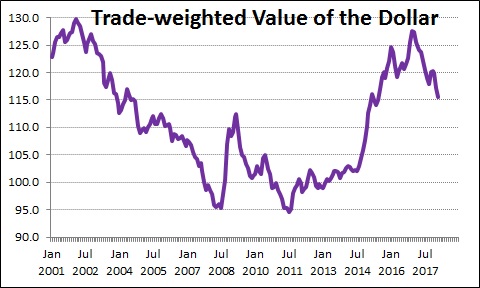

Similarly, the sharp increase in the dollar from mid-2014 through the end of 2015 lowered the prices of imported goods and helped to keep inflation in check. But the dollar has since reversed direction and began to decline immediately after the November 2016 election. Thus, the dollar’s impact on reducing inflation will also be temporary.

These factors help to explain much of the softness in the overall inflation measures, but the low core inflation rate in the U.S. has been more of a puzzle and harder to associate with a specific cause.

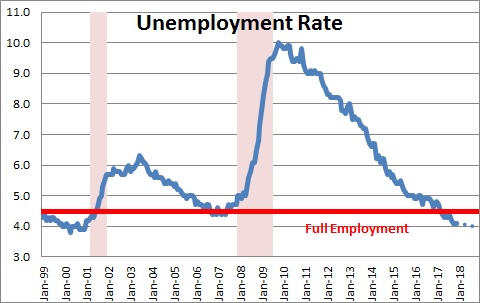

One possibility is that the full employment level of the unemployment rate – the level at which the labor market is exerting neither upward nor downward pressure on the inflation rate — could be lower than most economists estimate. The Fed believes that rate is currently 4.6% but its estimate, as well as estimates produced in the private sector, represent nothing more than educated guesses. Furthermore, all economists’ estimates of this full employment threshold have been trimmed by about one percentage point in the past couple of years as the seemingly tight labor market has failed to produce any significant upward pressure on wages. If full employment were, say, 4.2% or 4.3% it would better explain why wages have been rising so slowly.

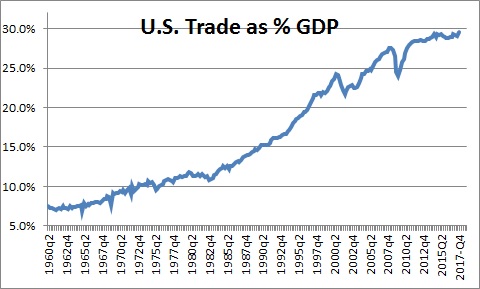

Second, developments in the global economy may be playing a role. Economic slack abroad may help to explain the inflation shortfall. For example, unemployment rates for many countries in Europe like France, Italy, and Spain all exceed the 10% mark. As a result, there is downward pressure on inflation rates in those countries. At the same time, as emerging economies become more integrated into the world economy the low wage rates available in these countries help to keep the global inflation rate in check. However, the Fed noted that measures of globalization such as the fraction of global trade as a percent of GDP have leveled off in recent years which suggests this factor may be less relevant today than it was five or ten years ago.

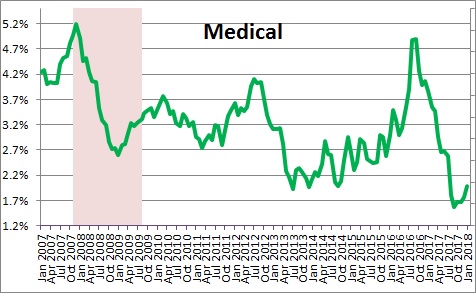

Third, some economists believe that the aging population could be exerting downward pressure on the inflation rate as, perhaps, retirees are more price conscious than other consumers. Furthermore, the recent slowdown in medical costs in the U.S. may be associated with health care reform. It is unclear the extent to which these price declines will persist.

Finally, the Fed believes technological changes in recent years have probably reduced pricing power for many industries. The increased prevalence of internet shopping allows consumers to easily compare prices from a variety of sellers which has limited the ability of firms to raise prices. But the Fed also notes that while this hypothesis seems to make sense, it is hard to square with the fact that profit margins remain high.

The bottom line is that Fed economists, like private sector economists, are puzzled by the stubbornly low rate of inflation. The FOMC concludes that inflation will, over time, move back to its target. Both we and the Fed believe the core PCE will rise from 1.5% currently to 1.9% by the end of this year which is virtually indistinguishable from the Fed’s 2.0% objective. Having said that, it is possible that new factors such as the ones described above (which are not currently included in the Fed’s models) could keep inflation subdued. But, at the same time, it must remain vigilant that the factors which have kept inflation in check for the past several years may prove to be transitory, in which case inflation could rebound more sharply than anticipated. It is a new world and we are all trying to understand it better. For now, the Fed should maintain its policy of raising short-term interest rates slowly with three rate hikes in store this year.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me