January 7, 2022

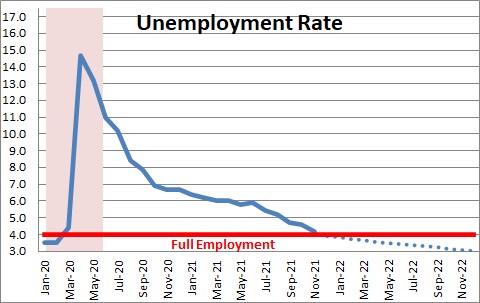

The anemic 199 thousand increase in payroll employment in December suggests that improvement in the labor market could be slowing. Nothing could be further from the truth. Workers today are simply reluctant to take jobs with companies. Instead, they are choosing to venture out on their own and start their own business or become contract workers and seek employment on a job-by-job basis but are never actually on a company’s payroll. These self-employed people are not included in the payroll employment data, but they are counted in the civilian employment measure that is used to calculate the unemployment rate. Since the recession ended in April 2020 civilian employment has risen far more rapidly than the closely-watched payroll employment series. As a result, the unemployment rate has fallen rapidly and, at 3.9%, is now slightly below the Fed’s full-employment threshold of 4.0%. This means that the Fed is finally going to switch gears and begin a long-overdue shift to higher interest rates. This should not be a great surprise to anyone. The Fed has been telegraphing this move for months. What is important is that the Fed’s current policy stance is so wildly stimulative that it will take years to get rate levels back to a neutral level. The projected rate hikes in 2022 and 2023 are unlikely to have any significant impact on the economy’s growth path.

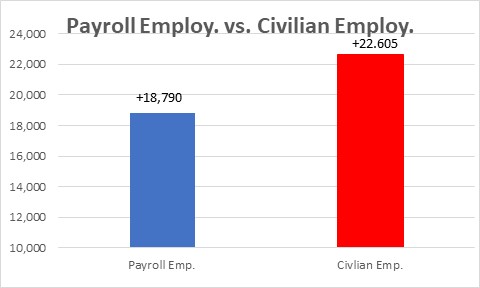

Payroll employment rose 199 thousand in December compared to a 450 thousand increase that had been expected. On the surface this appears to be a disappointing outcome. But that is not the case. The labor market has shifted dramatically in the 20 months since the recession ended in April 2020. Many workers, especially those in low paying jobs, are tired of working for somebody else and are venturing out on their own. This is evident from the difference between payroll and civilian employment. Payroll employment measures the number of workers that are on a company’s payrolls. It does NOT include self-employed workers. The civilian employment measure, which is used in calculating the unemployment rate, includes self-employed workers. Since the recession ended payroll employment has risen 18,790 thousand. Civilian employment has climbed by 22,605 thousand. Thus, it appears that the number of self-employed workers has climbed by 3.8 million. Their reasons for rejecting payroll employment are varied. Low pay. Long hours. Few benefits. Fear of catching COVID and perhaps spreading it to their families. An inability to find daycare workers to watch their kids so they can return to work. But the change is real and the payroll employment data provide a distorted picture of the labor market.

With the impressive gains in civilian employment the unemployment rate has been plunging. In the second half of last year it fell from 5.9% to 3.9%, or 0.4% per month. This is important because the Fed believes that full employment is achieved when the unemployment rate is 4.0% and it has pledged not to raise rates until such time as the unemployment rate reaches that threshold. It is there.

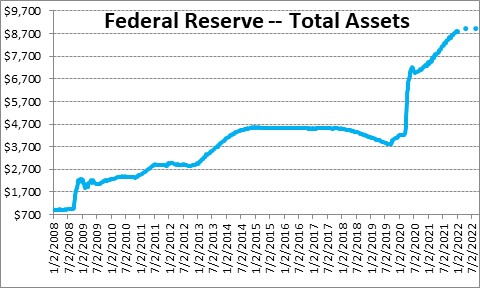

But before the Fed can begin to shrink its balance sheet and raise interest rates, it first needs to stop buying U.S. Treasury and mortgage backed securities. It is on as glide path to phase out its bond buying program by the end of March. That is a good first step, but what it really needs to do is shrink its balance sheet. Prior to the recession the Fed held assets of $4.3 trillion. Its security purchases have ballooned its balance sheet to $8.8 trillion currently. It plans to shrink its balance sheet gradually by not replacing its security holdings as they mature. If they do that the balance sheet could shrink by $2.5 trillion in the next three years – which still leaves it far too large.

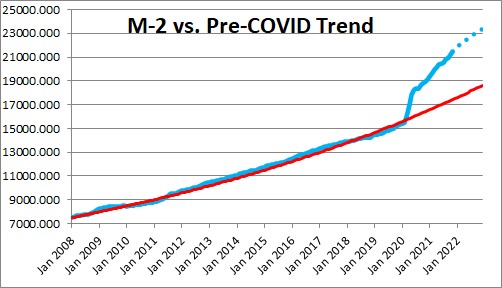

As it shrinks its balance sheet growth in the money supply will slow. That is a good thing. It is currently growing at a 13.1% pace which is about double the 6.0% rate at which it should be growing (roughly in line with growth in nominal GDP). If the Fed shrinks its portfolio, money growth should slow by the end of 2022. But it is so far above trend currently, and there is so much liquidity slopping around in the financial markets, that it will be providing fuel to an accelerated inflation rate for the foreseeable future.

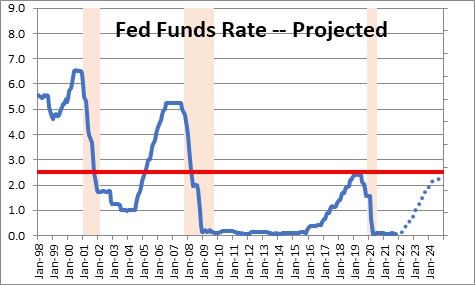

At the same time it plans to gradually increase the level of the funds rate which is effectively at 0.0% today. Its mid-December economic projections suggest that it plans three 0.25% rate hikes by the end of next year which would raise the funds rate to 0.9% by the end of 2022. But the Fed also believes that the funds rate is “neutral” — i.e., it neither stimulates nor retards the pace of economic activity – when it is 2.5%. It contemplates the funds rate rising slowly to the 2.1% mark by the end of 2024 – three years from now. That is way too low and slow. However, the Fed will be hard-pressed to simultaneously shrink its balance sheet and raise the funds rate more quickly than is currently envisioned. It is also important to remember that 2024 is a presidential election year and the Fed will not want to be in a position where its tighter monetary policy stance could inadvertently dump the economy into recession and perhaps alter the outcome of the election.

It is clear that the Fed will be raising interest rates steadily and shrinking its balance sheet slowly for the next couple of years. But the time when rates could rise to a level that they jeopardize the expansion is far into the future.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Stephen, from what I understand, Americans a moving away from food service and hospitality jobs to find better employment elsewhere. Suddenly there is a shortage of employees for low paying jobs. What to do? How about letting the thousands of immigrants who are trying to get into the the US come in and fill those jobs? The other alternative for highly repetitive, low paying jobs is robots. Two alternatives.

Darrel

HI Darrel,

I clearly opt for Option 1. I would eagerly support the notion of letting in some of those people at the border come in to fill some of those low-paying jobs. One the job openings in November roughly one-half of the private sector job openings were in retail trade, transportation and warehousing, health care and accommodation and food services. Meanwhile, broaden the border opening for some of those with the tech skills that we also seem to need. Having said all that, I suspect that politically that is not going to happen.

Re: robots, we are already seeming them in fall sorts of places. Warehouses are becoming increasingly automated. Driverless cars are becoming more commonplace (trucks may not be too far behind), order yyour meal with an app on your phone and it will be ready when you arrive. I suspect you know far more about the implementation of robots than I ever will.