November 2, 2018

The market’s attention recently shifted to labor costs which have begun to accelerate. Most economists fear that rapidly rising wages will lead to a further pickup in inflation, force the Fed to quicken the pace of rate hikes, and eventually lead to the demise of the expansion. But people are looking at the wrong thing! They should be looking at labor costs adjusted for changes in productivity. Doing so completely alters the conclusion.

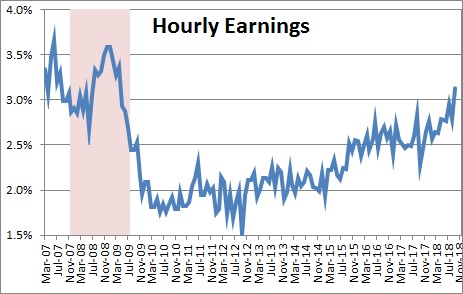

There are lots of different measures of wage pressures. Many people focus on average hourly earnings. We see it every month as part of the employment report. It is easy to track. This measure of earnings has risen 3.1% in the past year which is the largest yearly increase in a decade. It is clearly accelerating and making people nervous. But this series only tells us about changes in hourly wages. It is does not tell us anything about what is happening with benefits.

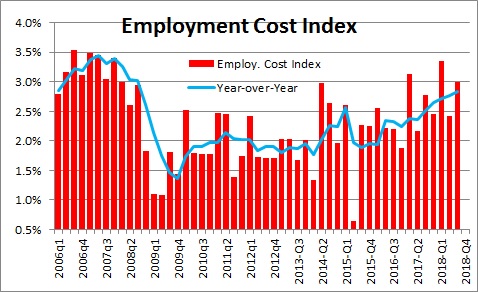

The employment cost index is less well known largely because it comes out once per quarter. It is a broader measure of labor costs and includes changes in both hourly compensation and benefits. Recently released data for the third quarter show a year-over-year increase of 2.8% which, like average hourly earnings, is the fastest in a decade. Given that labor costs are about two-thirds of a firm’s overall cost, many economists now conclude that a pickup in labor costs will create an incentive for firms to raise prices. Not so fast. There is more to the story.

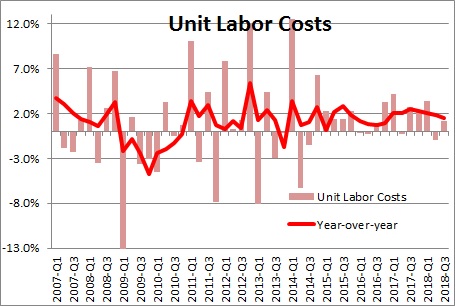

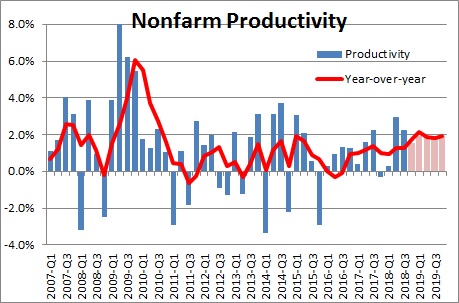

Suppose I pay you 3% higher wages. My labor costs have risen, and I will be tempted to raise prices. But what if I pay you 3% more money because you are 3% more productive? I really do not care. You are giving me 3% more output. You have earned your fatter paycheck. So, what we need to follow are labor costs adjusted for the changes in productivity. Economists have a fancy word for that concept — “unit labor costs”. This index is even more obscure. It is buried in the quarterly report on productivity. This past week the Labor Department published data on productivity and unit labor costs for the third quarter. It showed that ULC’s rose a modest 1.2% in the third quarter and have risen just 1.5% in the past year. More interesting is the fact that this series is suddenly trending lower. In the middle of last year unit labor costs were rising 2.5%. They have since slowed to 1.5%. How can that be? Answer: Productivity growth has accelerated.

The increase in unit labor costs can be split between two parts. Compensation growth in the past year of 2.8% is about the same as other measures of wage costs. But productivity has risen 1.3%. Thus, unit labor costs – the difference between the two numbers — has risen 1.5% and, as noted earlier, they are slowing down.

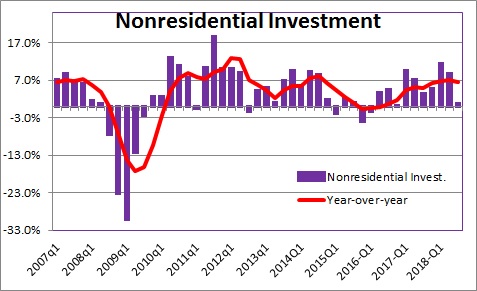

Without a doubt faster growth in productivity is a result of the sustained pickup in investment spending since the November 2016 election. It has been fueled by the cut in the corporate tax rate, repatriation of earnings from overseas by large multi-national firms, and an extraordinary pace of deregulation.

We expect these same factors to sustain growth in investment spending for the foreseeable future. In addition, with the unemployment rate at nearly a 50-year low and workers hard to find, firms might consider spending money on technology to boost productivity growth amongst existing employees and increase output. Additional spending on technology from this source should enhance investment spending in the quarters ahead. Productivity will continue to climb and upward pressure on wages should be largely offset. Next year we expect compensation to increase 3.7% in 2018 (versus 2.8% currently) because of additional tightness in the labor market. We also expect productivity to rise 1.8% (versus 1.5% right now). As a result, unit labor costs by the end of next year should rise 1.8% (versus 1.5% now). They should continue to climb at a slower pace than the Fed’s targeted inflation rate of 2.0%. Virtually no upward pressure on inflation from this source.

Technology has completely changed the game. It is boosting investment and productivity. It is raising our economic speed limit. It is accelerating growth in our standard of living. And it is helping to keep inflation in check by boosting productivity and offsetting much of the increase in wages. And we are just beginning to recognize the extent to which this has occurred.

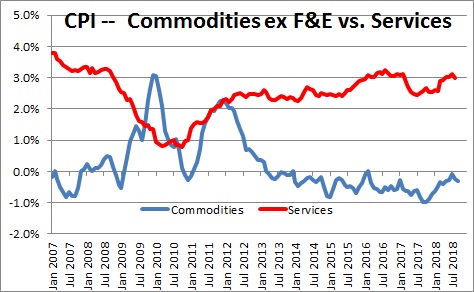

As a slightly different way of highlighting the impact of technology on inflation, split the CPI into two pieces – changes in good prices versus services. In the past year goods prices have declined 0.3%. Prices of services rose 3.0%. Why? Goods-producing firms have virtually no pricing power. Whenever consumers want to buy anything, we shop the internet, Amazon in particular. We can find the lowest price in our city, our state, the country, or even the world. Thus, prices are not rising for roughly one-third of the goods and services offered for sale in our economy. That clearly is keeping the inflation rate in check.

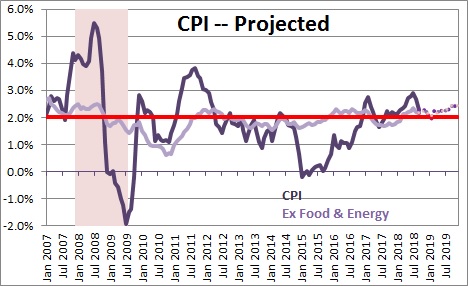

The inflation rate may continue to climb in the months and quarters ahead, but its acceleration will be very gradual. Last year the CPI excluding food and energy rose 1.8%. It should rise 2.2% this year and 2.4% in 2019. Such a gradual pickup in inflation will not bother the Fed. In fact, they have already said they will accept an inflation rate slightly above target for a while because it was so far below target for an extended period.

Accelerating wages bother people because they fear it will lead to more rapid inflation. But they are getting themselves spooked because they are looking at the wrong thing. They should be looking at labor costs adjusted for changes in productivity or unit labor costs. When they do that, they find that this adjusted wage measure is not only growing at a rate below the Fed’s 2.0% targeted rate of inflation, it is slowing down. Don’t get alarmed quite yet.

Stephen D. Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me