January 6, 2023

The extreme labor shortage that virtually every business in the country is experiencing is not going away. At the end of last year the labor force is estimated to be 2.9 million workers shy of where it should be. Some have died from COVID. Many others have retired. Some may have moved back in with their parents and are living off generous government benefits. The reality is that we still cannot fully explain why so many workers have disappeared. What is clear that these missing workers are not suddenly going to materialize, and the labor market is likely to remain tight for the foreseeable future. That makes the Fed’s job harder. As long as a labor shortage exists, employers will have to bid aggressively to find the bodies they need which will, in turn, put upward pressure on wages. Given that labor costs are about two-thirds of a firm’s total cost, the steady increase in wages will put upward pressure on inflation as business pass those higher labor costs on to their customers. As a consequence, it will be difficult for the inflation rate to decline quickly and Fed will have to keep raising rates. There is an obvious solution to this labor shortage. It lies South of the border.

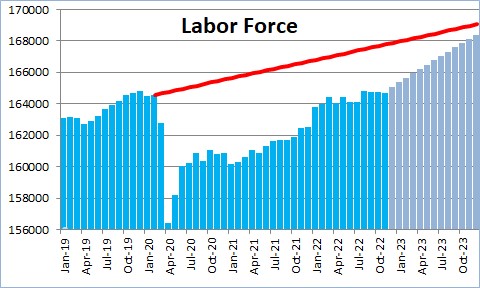

After three years the labor force has returned to the size it was just prior to the recession. The problem is that it should have been growing roughly in line with population or about 0.7% per year. The red line shown below is roughly where the labor force should be. The blue bar is where it is. The difference between the two currently is 2.9 million workers.

COVID certainly played a role in shrinking the labor force. We know that 1.1 million people died from COVID. Of those, 0.8 million were over the age of 65. Most of those older individuals were retired already, but some were still working. The remaining 0.3 million people were in the prime-working-age category of 25-55. So between prime working age individuals and some older folks, perhaps 0.5 million of the 2.9 million workers missing from the labor force can be attributable to COVID.

Another large group appears to have retired. Looking at the changes in the labor force of those in the 55-65 year old age bracket and those over age 65, perhaps another 1.0 million workers retired.

But these two explanations only account of perhaps 1.5 million of the 2.9 missing workers. Other explanations abound but are difficult to quantify Some workers appear to have moved back in with their parents and are living off still relatively generous government benefits. Some may have become day-traders trying to become rich (albeit temporarily) by trading Bitcoin.

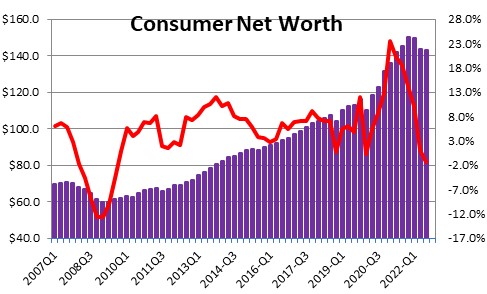

As the economy softens and the Fed keeps raising interest rates, almost everybody fears a recession ahead. If that is the case, stock prices are likely to decline further. Home prices will continue to fall. Much of the run-up in consumer net worth in the past couple of years may disappear. For this reason, some workers still missing from the labor force may start looking for jobs. That would help.

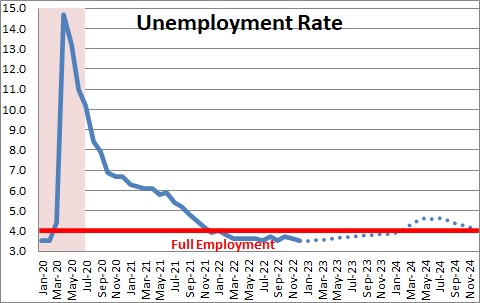

However, the labor market remains tight by any standard. The unemployment rate is 3.5%. The Fed believes the economy is at full employment when the unemployment rate is 4.0% With slow growth in the labor force the unemployment rate should remain at or below that full employment threshold throughout 2023. Even with the prospect of higher interest rates and somewhat slower GDP growth, we believe the unemployment rate will increase only 0.4% in 2023 which would put it at 3.9% at yearend.

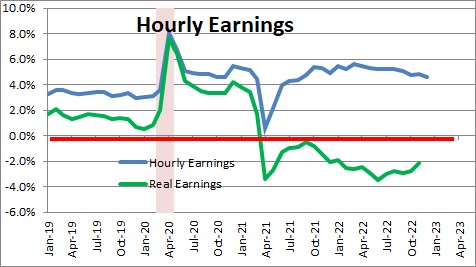

If the labor market remains tight, employers will have to bid aggressively to find the workers that they need. In the past year average hourly earnings have risen 4.6%. (The Atlanta Fed’s “wage tracker” has an even bigger 6.4% increase in wages.) With inflation rising even more quickly, real wages have fallen 2.1% in the past year. With falling real wages, individual workers and unions will pressure employers for even faster growth in earnings in the months ahead.

Because wages represent two-thirds of a firm’s overall costs, rising wages will translate into higher prices and faster inflation as firms pass those higher labor costs on to their customers. If wages keep rising at a 4.6% rate, that is more than double the Fed’s 2.0% inflation target.

It is certainly appropriate for the Fed to slow the pace of tightening from 0.75% at every FOMC meeting to 0.5%, but it cannot stop as long as the inflation rate remains far above its target. The lingering question is how high the funds rate must go to reduce employment and alleviate some of the upward pressure on wages. The Fed thinks that only a slight increase in the funds rate to 4.6% will do the trick. We think the peak funds rate is more likely to be 6.0%.

The lack of growth in the labor force is causing some of the upward pressure on the funds rate. This situation is not going to solve itself any time soon. But there is an easy fix if our leaders in Washington were to avail themselves of the opportunity. We appear to have millions of people lined up at our southern border trying to enter the United States to work, to study, and to improve their standard of living. Certainly Congress can devise an appropriate border policy that would allow two or three million qualified workers into this country. Doing so would quickly alleviate the worker shortage, stem much of the upward pressure on wages, and help the Fed reduce inflation to its 2.0% target much more quickly.

Unfortunately, that is not going to happen. Congress remains as dysfunctional as ever – perhaps even more so since the election.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Your comment about Washington is right on. We had our annual planning retreat today where we discussed the continuing labor shortage. Our country needs engineers, programmers, carpenters, plumbers, landscapers…the list goes on. Since Americans won’t or can’t fill these jobs we need immigration reform right now. Tell your representative to get to work and FIX this.

somehow I do not think they are going to listen to me.