November 12, 2012

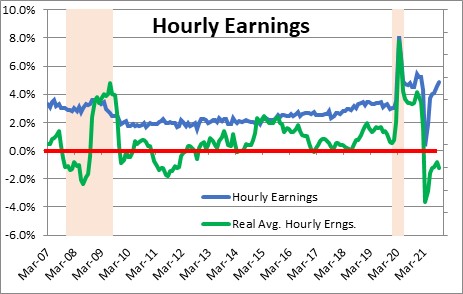

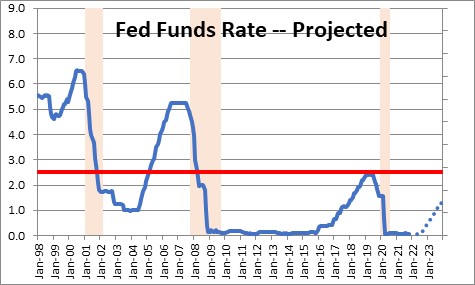

The September CPI report made it clear that the recent burst of inflation is not going away any time soon and may be getting worse. This should not be a great surprise but it is, apparently, to Fed officials. Maybe the unexpected September data will serve as a wake-up call. We doubt it. The Fed seems entrenched in its view that the run-up in inflation is temporary and it intends to raise rates very slowly. In September its plan was to lift the funds rate to 1.0% by the end of 2023 and 1.5% by the end of 2024. But the Fed believes a neutral level for the funds rate – the level at which its policy is neither stimulating nor retarding the pace of economic activity – is 2.5%. What that means is that the Fed intends to maintain an accommodative monetary policy stance for the next three years. Seriously? But the Fed’s leadership is about to change. Fed Chair Powell may or may not be re-appointed. There is already one vacancy on the Fed Board and two others, Vice Chair Clarida and Fed Governor Quarles, are resigning. That gives Biden the potential to appoint four new Fed officials. Given that Biden will name their replacements, it is unlikely that the new team will be any more concerned about inflation than the current group. That is a scary proposition. In the past year nominal wages have risen a solid 4.9%. But inflation has completely offset that gain. Real wages have fallen 1.2% and consumers have noticed. Falling real wages will cause workers and unions to seek even bigger wage gains which will worsen the inflation problem. This did not have to happen.

Economists at the Board of Governors of the Fed are top-notch. By virtue of having literally hundreds of economists at their beck and call, the Fed has the manpower to devote far more resources to a problem than any group in the private sector. Given the Fed’s in-depth analysis all private sector economists anxiously await the Fed’s latest forecasts. But yet its predictions of GDP growth and inflation since the pandemic-induced recession in the spring of 2020, have widely missed the mark. That is a problem because its forecasts are the primary driver of the FOMC’s interest rate decisions. It is hard to envision the Board’s staff being privy to some secret information that the rest of us cannot see. With few exceptions we all see the same thing. How can it be that the Board has missed the causes of the inflation run-up by such a wide margin? Is the Board staff less competent than it has been in the past? Perhaps, but we doubt it. Or could it be that politics has entered the equation and that the FOMC – Fed Chair Powell in particular – has embraced modern monetary theory which says that money supply growth and additional government debt do not matter? We hope that is not the case. But when the Fed chair says that the relationship between money supply growth and inflation is a concept that will just have to be “unlearned”, he sounds like he has dipped into the MMT Kool-Aid.

There are many reasons why the recent inflation statistics should not be a surprise and why inflation is not going to retreat any time soon.

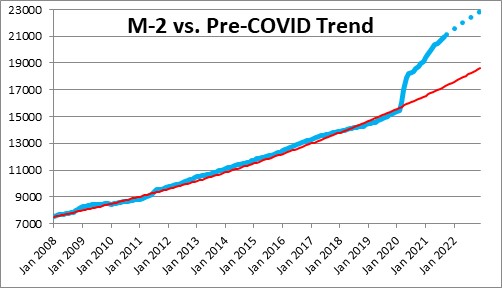

First of all, last March and April the Fed purchased $2.5 trillion of securities. After having grown at a 6.0% pace for years, money growth surged to 42% and 75% in those two months and climbed far above its 6.0% growth trajectory. Today it is $3.7 trillion above that trendline. Why are we surprised that the economy is on a roll and that inflation is surging? There is simply too much money chasing too few goods. That situation is not going to change until such time as the Fed curtails money growth to a below-trend pace of 4.0% or less. Phasing out Fed purchases of securities will cause it to slow, but not to that pace.

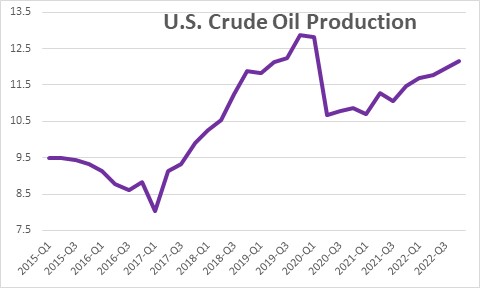

With regard to specific factors boosting inflation, crude oil prices have climbed to $83 per barrel and the Biden administration is pleading with OPEC to boost production. But at the same time Biden is doing everything in his power to phase out the fossil fuel industry. As a result, U.S. oil production has not yet returned to its pre-recession pace.

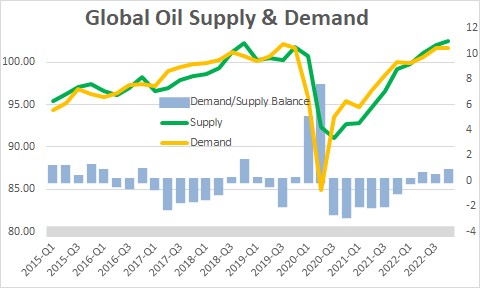

The Energy Information Administration expects the demand for oil to exceed supply through the spring of next year. Oil prices are not going to decline any time soon.

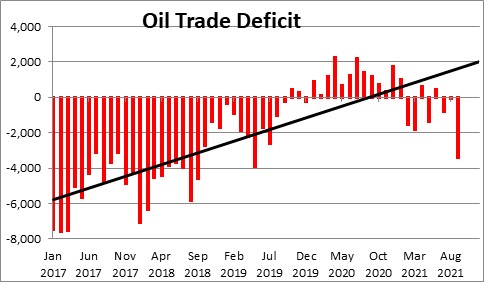

And, perhaps worse yet, reduced U.S. oil production has caused oil exports to decline and turned an oil trade surplus back into a deficit. The U.S. is, once again, dependent on OPEC oil.

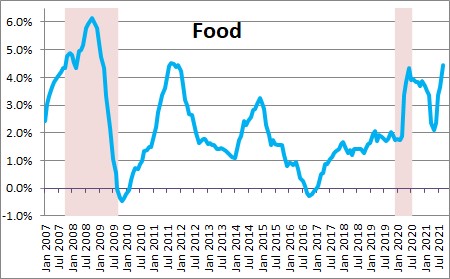

Food prices have risen 5.1% in the past year. They, too, are unlikely to retreat any time soon.

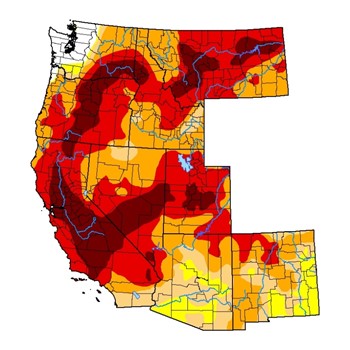

This, too, should not be a surprise. The National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska estimates that 52% of the West is experiencing “extreme” or “exceptional” drought conditions (80% in California). Droughts and fires have taken a toll. It is hard to imagine food prices falling much without more rain.

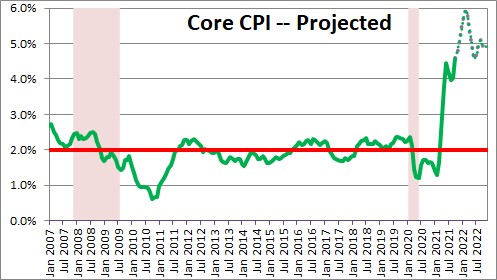

The so-called “core” CPI rose 0.6% in September and has climbed 4.6% in the past year. It is hard to argue that this is a temporary increase. Hotel prices, for example, are 6.2% higher than they were prior to the pandemic. Restaurant prices are 8.2% above their pre-pandemic level. Something else is going on. Back in 1973 Pink Floyd sang “Money, so they say, is the root of all evil today.” Maybe the band was on to something.

Economists are fond of excluding the food and energy categories from their calculation of inflation because they are so volatile. Usually, that is the case. A hurricane can curtail U.S. oil production for a month or so, but it quickly returns. A drought will boost food prices but, eventually, it will rain and prices will decline. In today’s world neither food nor energy prices seem likely to drop any time soon. Perhaps we should be focusing on the overall CPI as the true gauge of inflation. That measure has risen 6.2% in the past year versus 4.6% for the core rate. Perhaps the problem is worse than we think.

Rising inflation is not just a topic for economists to debate. It has real world consequences. For example, hourly compensation has risen 4.9% in the past year. That sounds great. But at the same time inflation has 6.1%. As a result, real hourly wages have declined 1.2%. inflation has completely countered the wage gain. The buying power of hourly workers is 1.2% less today than it was a year ago. The Biden administration is supposedly trying to watch out for the little guy. Its policies are making the problem worse.

The consumer has taken notice. The University of Michigan survey of consumer sentiment fell in November to its lowest level in a decade. The survey director, Richard Curtain said, “Consumer sentiment fell in early November due to an escalating inflation rate and the growing belief among consumers that no effective policies have yet been developed to reduce the damage from surging inflation. One-in-four consumers cited inflationary reductions in their living standards in November, with lower income and older consumers voicing the greatest impact.”

In our view, the rising inflation rate is cause for concern. It requires Fed action. And not just gradually slowing its pace of purchasing U.S. government and mortgage backed securities. It requires higher interest rates. Fed officials are currently planning to raise the funds rate from near 0% today to 0.3% by the end of next year, 1.0% by the end of 2023, and 1.8% by the end of 2024. But yet the Fed believes the funds rate is “neutral” at 2.5%. Think about it. The Fed plans to keep adding fuel to the inflation fire for the next three years. The inflation rate is not going to retreat until such time as the Fed gets serious about combatting its rise. That time is not yet in sight.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

From the WSJ “One irony of inflation is that while it’s bad for working Americans, it’s great for the government. Tax revenues soar as nominal profits and incomes rise, and for evidence simply look at the boom in state and local government coffers. They’ve rarely had it so good, but don’t expect them to be frugal spenders”

It does seem the expansion of the money supply does benefit a certain segment.

Hi Bill,

I agree completely. I also agree that they are likely to factor that into their budget projections which will give them the ability to pay for additional spending. Too bad.

Steve