October 4, 2024

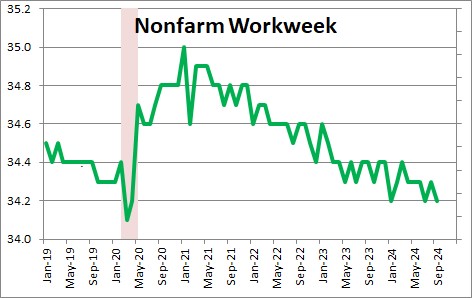

In any given month employers can boost output by either additional hiring workers or by lengthening the number of hours that their employees work. Payroll employment climbed by 254 thousand in September. At the same time the nonfarm workweek declined 0.1 hour to 34.2 hours.

The combinations of robust employment and fewer hours worked statistics seem to suggest that the labor market has weakened. However, any labor market weakening thus far has been modest.

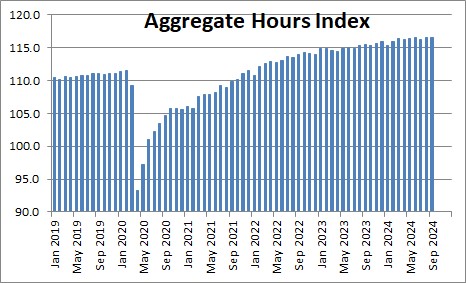

The changes in employment and hours worked are reflected in the aggregate hours index which declined 0.1% in September to 116.5 after having risen 0.3% in August. This index increased 0.2% in the third quarter which we believe is reasonably consistent with our GDP forecast for that quarter of 2.0% (because of an expected increase in productivity).

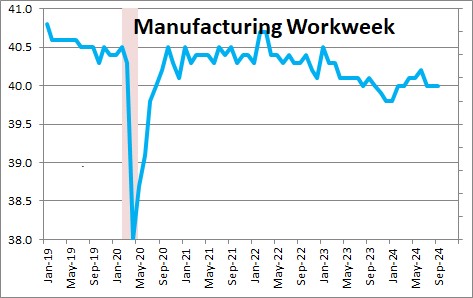

The factory workweek was unchanged in September at 40.0 for the third straight month. The manufacturing sector has been slowing gradually in response to higher interest rates. Lower rates in the months ahead should help.

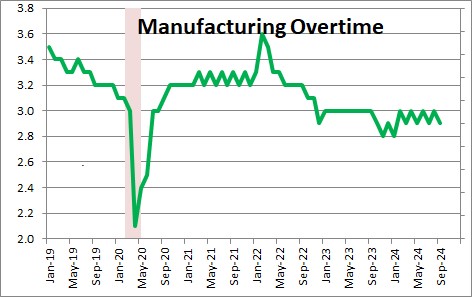

Overtime hours fell 0.1 hour in September to 2.9 after having risen 0.1 hour in August. Manufacturers have adjusted to reduced demand by cutting overtime hours. Having said that, overtime hours have been bouncing around at 2.9-3.0 hours for the past year.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, SC

Follow Me