February 3, 2023

The economy may be softening, but you get little support for such an argument from the January employment report which was unambiguously strong. That raises several questions. Will growth slow enough to bring down the inflation rate? Will significantly higher interest rates be required to make that happen?

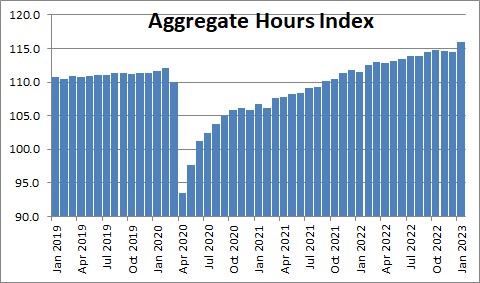

In any given month employers have a choice of hiring more workers or working their existing employees longer hours. In January they did both – big time! Payroll employment skyrocketed by 517 thousand in January while the nonfarm worked surged upwards by 0.3 hour to 34.7 hours. Multiplying one by the other gives a sense for the aggregate number of hours worked in that month. That index of economic activity jumped 1.2% in January. Even making conservative estimates for this index in February and March it is hard to come up with a quarterly increase less than 3.0%. Presumably these people were making something. That adds up to the likelihood that first quarter GDP will increase at a rate far in excess of what is currently expected. Accordingly, we have raised projected GDP growth for the first quarter from 1.2% to 1.7% but, as suggested above, the actual growth rate in the first quarter could be considerably stronger than our revised estimate. The notion that the economy is already in recession just went out the window. Maybe it is coming, but it clearly has not yet arrived.

Our sense is that the employment report for January may have been distorted by Christmas hiring. If firms hired fewer than normal workers in October and November because they feared that it might be a relatively soggy consumer spending season, then that means they would have laid off far fewer than normal workers in January – hence, the surprisingly robust hiring gain in that month. But even if that were true, average employment in the past three months has risen by 356 thousand per month — still a super-charged pace of hiring.

All economists are expecting slower growth given that the Fed has raised the funds rate from 0% at the end of 2021 to 4.75% currently and likely somewhat higher in the months ahead. But given GDP growth of 3.2% in the third quarter, 2.9% growth in the fourth quarter, and 1.7% (or higher) in the first quarter, is it time for a rethink? The Fed may have been raising the funds rate, but every other market interest rate has declined significantly in recent months. Since November 7, the 2-year note yield has fallen 0.5%, the 10-year has declined 0.7%, and the 30-year mortgage rate has dropped by 0.9%. In other words, the Fed may be raising the funds rate and trying to slow the pace of economic activity, but these rate declines have countered what the Fed is trying to do. Lower rates could easily boost GDP growth in the first half of this year and re-ignite inflation.

The potential GDP growth rate for the U.S. (or the economic speed limit) is estimated to be 1.8%. When the economy is at full employment, which certainly seems to be the case now (with the unemployment rate at 3.5% versus a full-employment level of presumably about 4.0%), then GDP growth that exceeds 1.8% is likely to boost the inflation rate. Given GDP growth in the final two quarters of last year and what it might be in the first quarter, suddenly one has to question whether whatever growth slowdown we eventually get will be sufficient to lower inflation to the 2.0% mark. The Fed needs to see a protracted period of GDP growth less than 1.8% to feel comfortable that it is on the right track. Will it get it? Our sense is that growth will not slow enough to bring inflation back to 2.0% without additional rate hikes.

The Fed seems on a path to raise the funds rate two more times by 0.25% each time taking it to 5.25% by March and leaving it there through the end of 2023. The markets believe the Fed will only raise it to a peak rate of 5.0% and will actually cut the funds rate to 4.5% by yearend – despite Fed comments that it has no such intention of doing so during that time frame. But this is normal behavior. The Fed gives us some idea of where it thinks it is headed – which may or may not be accurate – and the markets make bets on whether the Fed has it right.

But what is surprising to us is that nobody is talking about the possibility that the economy might be sufficiently strong, and the inflation rate sticky enough, that the Fed needs to raise the funds rate well beyond the 5.25% it is suggesting at the moment. In December we thought the peak funds rate might be 6.0%. We lowered that last month to 5.5% given the soft economic data for December and lower-than-expected inflation. Right now we are thinking about raising it to the 6.0% market (although we have not yet pulled the trigger).

Sadly, nobody – neither the Fed nor any private sector economist – can give you anything other than a cloudy picture of what is likely to happen in the months ahead. Unfortunately, all of us are guessing. But given the relatively benign forecast by the Fed that it might need to raise the funds rate by only an additional 0.5%, and the markets expectation that rates will actually be lower by yearend, our bet is that both groups are currently way off base.

As always, we will see.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me