January 10, 2019

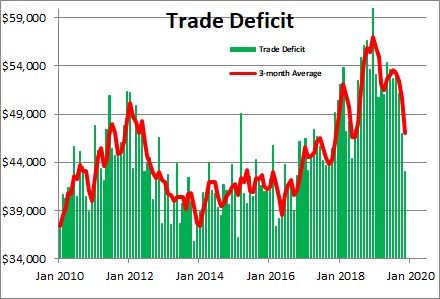

We recently learned that for November the trade deficit shrank $3.9 billion to $43.1 billion after having narrowed $4.2 billion in October. The impressive decline in the trade gap may appear to be a good thing, but the deficit is contracting for the wrong reasons – tariffs imposed by the U.S., China, and other countries are taking a toll.

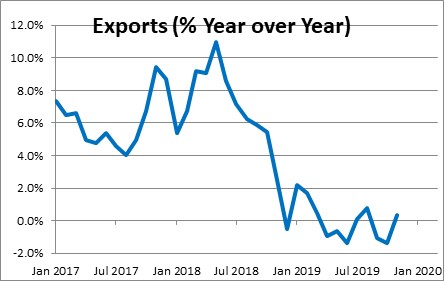

In the past year exports have risen 0.3% but that is far slower than when the trade war began in April 2018. At that time exports were rising at nearly a double-digit pace. But the Chinese tariffs imposed on many U.S. products has sharply curtailed growth in exports and are the primary reason for the current weakness in manufacturing.

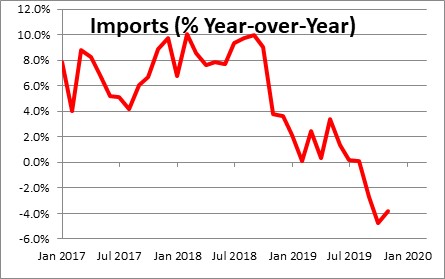

At the same time, the higher tariffs imposed by Trump on a wide range of goods imported into the United States has caused imports to contract by 3.8% in the past year. Like exports, when the trade war began two years ago U.S. imports were climbing at almost a double-digit pace.

From a GDP standpoint trade is a good thing. All countries benefit by having a broader range of goods and services available to them at lower prices with trade than in the absence of trade. Perhaps the best way of gauging this impact on the U.S. economy is to look at the growth rate of exports and imports combined. A couple years ago total trade was climbing at an 8.0% pace. In the past year it has declined by 2.0%. In a trade war everybody loses. Because trade is only 10% of the U.S. economy compared to about 50% for most other countries, the trade war may have weakened the U.S. economy less than others but, make no mistake, it has taken a toll everywhere.

From Trump’s perspective, however, the tariffs may have a broader goal. The Chinese simply do not play by the same rules as other countries. They steal trade secrets, do not respect copyright and patent laws, and force companies wanting to do business there to share their trade secrets. If tariffs can force China to alter its business practices, then perhaps the loss of a couple tenths of a percent of GDP growth is not such a bad tradeoff.

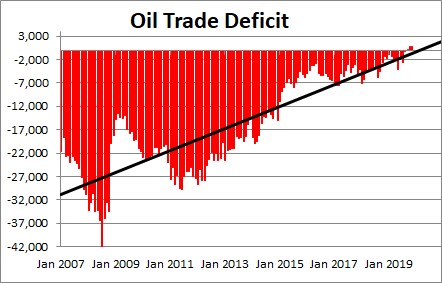

While the trade war has been dominating the headlines in the past couple of years, there is something else going with respect to trade that should not be overlooked. Technological developments in the oil industry in the form of fracking and horizontal drilling have shrunk the oil trade deficit from $30.0 billion a decade ago and turned it into a trade surplus! In the past three months oil exports have exceeded imports by about $1.0 billion. The U.S. has become a net petroleum exporter! That development was unimaginable a decade ago.

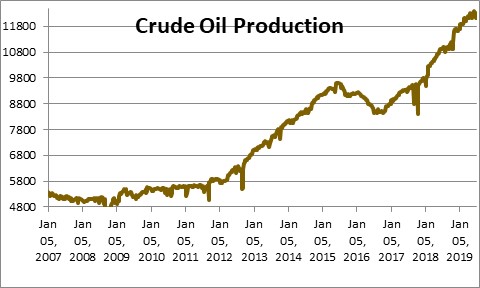

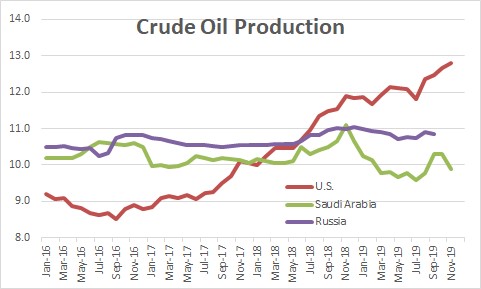

What it means is that the world is not nearly as dependent on OPEC oil as it has been in the past. Gone are the days when OPEC countries were able to curtail the global supply and push prices above $100 per barrel. Should they attempt such a maneuver today, U.S. producers will quickly jump in to increase production and bring prices back down. U.S. crude oil production has increased from about 5.0 million barrels per day a decade ago to 12.3 million barrels per day currently, and the Department of Energy expects it to climb further to 13.3 million bpd by the end of this year.

In the process, the U.S. became the world’s largest producer of crude oil in June 2018 and the gap between its production and that of Russia and Saudi Arabia – the next two largest crude oil producers – continues to widen.

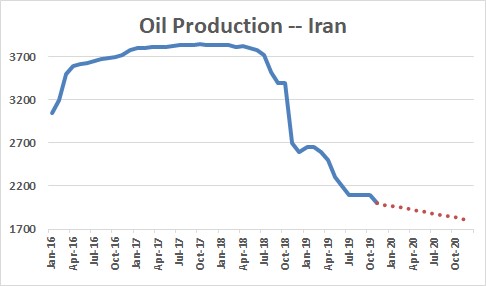

In another oil-related development, tensions in the Mideast jumped to the forefront recently as hostilities between the U.S. and Iran flared up briefly. Trump refrained from further military action against Iran but chose, instead, to enhance sanctions on that country. Already existing U.S. sanctions are crippling the Iranian economy. Oil production has been cut in half from almost 4.0 million barrels per day a couple of years ago to 2.0 million bpd currently. As a result, the IMF estimates that Iranian GDP declined 4.8% in 2018 and an additional 9.5% last year. Clearly, sanctions have taken a toll and the additional sanctions Trump imposed on Iran this week will likely cause GDP to contract for a third consecutive year.

As we see it, tariffs exert a negative impact on trade both in the U.S. and elsewhere. That is not good. But if those tariffs can force China to alter its business practices and stop stealing trade secrets from the U.S. and elsewhere, force China to respect intellectual property rights, and stop China from requiring companies wanting to do business in China to share their trade secrets, then perhaps the loss of a couple tenths of a percent of GDP growth is acceptable.

Furthermore, if sanctions can put enough pressure on Iran to back away from its aggressive military tactics in the Middle East than perhaps that, too, is a good thing. Tariffs and sanctions may not be an ideal solution to either problem, but they serve a purpose.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me