March 29, 2019

The expansion is now within three months of becoming the longest expansion on record. Perhaps for that reason most economists conclude that a recession is lurking by the end of this year and try to find the dark side of every economic indicator. We don’t buy it. Expansions do not end simply because they reach some chronological milestone. They end because the economy overheats, the Fed raises interest rates rapidly, goes too far, and eventually the economy slips over the edge into recession. This is not that.

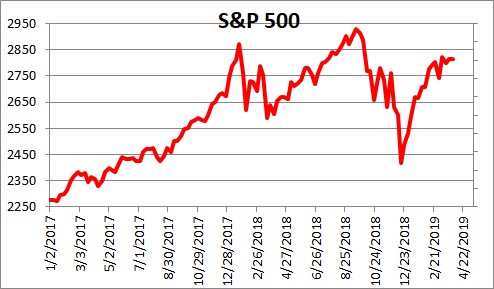

Let’s start with GDP growth. Fourth quarter GDP growth was revised downward from an initially-published 2.6% to 2.2%. Economists quickly pointed out that growth has slowed steadily from 4.2% in the second quarter, to 3.4% in the third, to 2.2% in the fourth, with even more anemic growth of 1.5% expected in the first quarter of this year. However, those economists ignore the fact that the recent slowdown may have been negatively impacted by the 20% drop in stock prices and the government shutdown. Those temporary restraining factors have since been reversed.

In response to the combination of slower growth overseas, a rate hike by the Fed in mid-December, its announcement that two more rate hikes were likely this year and the government shutdown, the stock market went into a 20% tailspin. But the Fed now says it plans no further rate hikes this year and the government shutdown has ended. Stocks have rebounded quickly and are now just 4% below their mid-September record high level.

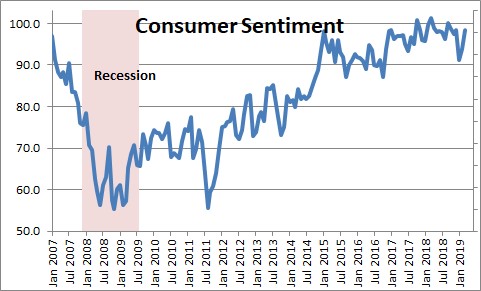

Like stock prices, measures of consumer confidence dipped briefly but have since rebounded and remain close to their previous high levels and are consistent with consumer spending climbing at a steady 2.5% pace this year.

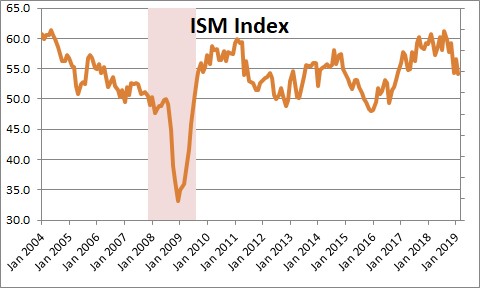

The Institute for supply Management’s index of activity in the manufacturing sector slipped from a near-record level of about 60 in the fall, to 54.2 in February. But, according to the ISM group, its current level is consistent with 3.3% GDP growth. An identically constructed index for non-manufacturing activity has completely erased its earlier decline and is consistent with 3.9% GDP growth. Business leaders remain positive.

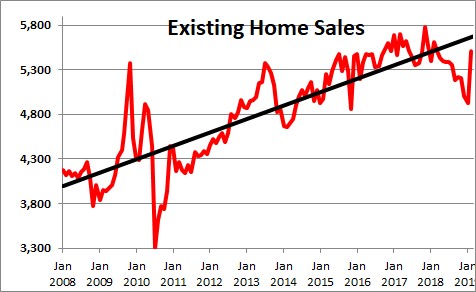

The housing sector has been under downward pressure for more than a year. But things are looking up. Existing home sales jumped almost 12% in February and erased much of the drop experienced throughout 2018. New home sales have rebounded just as sharply.

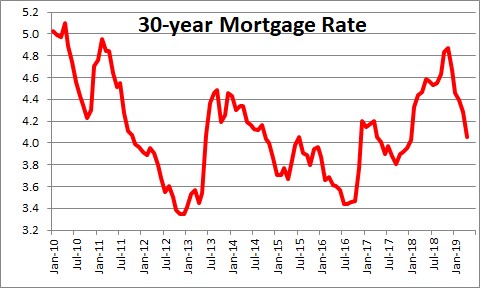

Furthermore, mortgage rates have fallen 0.9% in the past couple of months from 4.9% to the 4.0% mark. That is the lowest rate since January of last year. That will undoubtedly provide support to home sales in the months ahead. As a result, we expect housing starts to climb by about 9% this year despite a shortage of available construction workers.

None of this sounds remotely close to a recession scenario. Indeed, following an expected 1.5% growth rate in the first quarter of this year, we anticipate GDP growth of 2.8%, 2.9%, and 2.8% in the final three quarters of the year. That would give us 2.6% growth for the year. The Fed, which is less optimistic, looks for GDP growth of 2.1% this year. Because the Fed believes the economic speed limit currently is 1.8%, a 2.1% growth rate for the year in Fed terms is relatively robust and inconsistent with a lower rates scenario.

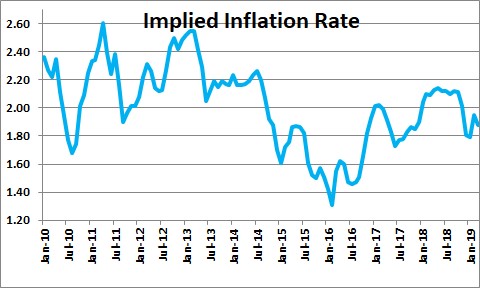

Some economists think that the inflation rate will continue to slow. That seems unlikely. The implied rate for inflation expectations over the next 10 years remains relatively steady at 1.9%. The Fed looks for the core personal consumption expenditures deflator (its preferred inflation gauge) to rise 2.0% in 2019 (it is currently climbing at a 1.8% pace). Its inflation target is 2.0%. A significantly slowdown in inflation is not going to happen.

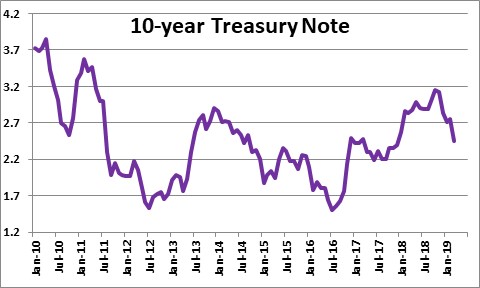

Many economists base their recession forecasts on the slight inversion of the yield curve. While it is true that an inverted curve is a leading indicator of recession, we think they are reaching the wrong conclusion because they are not looking at why the yield curve has inverted. Typically, the economy grows at a reasonably rapid pace, inflation begins to climb, the Fed responds by raising rates quickly and, at some point, goes too far. Hence, an inverted curve is usually a sign that the Fed has tightened “too much”.

Please note that we have two pre-conditions for a recession– a funds rate above the 5.0% mark and an inverted yield curve. The funds rate today is 2.4%. Most economist believe a “neutral rate” – one which neither stimulates the economy nor slows it down – is about 2.8%. Fed policy is not even close to being “too tight”.

And regarding the inversion of the yield curve, it has not inverted in the usual way by having short rates rise rapidly and eventually become higher than long rates. Instead, an expectation of slower GDP growth, lower-than-expected inflation, and an eventual Fed easing move, has pushed long rates below short rates. Indeed, in the past six months the yield on the 10-year note has fallen by 0.8% from 3.2% to 2.4%. A yield curve that inverts because long-term interest rates have fallen dramatically, does not carry the same meaning as an inverted curve caused by rising short rates and “too tight” Fed policy. The slight inversion of the curve that is occurring currently is not a harbinger of recession.

Economists currently want to find the dark side of every economic indicator that is released because they are sure a recession is just around the corner. But as the year progresses a rebound in the pace of economic activity and steady inflation should cause them to re-evaluate their gloomy outlook. However, they will only do so grudgingly. Keep the faith. All is well.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me