February 7, 2019

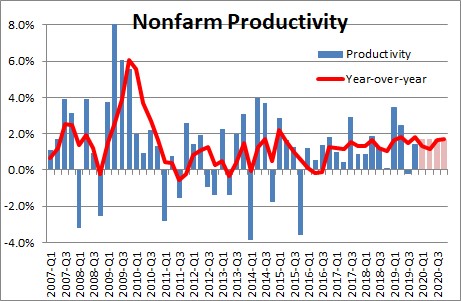

What seems to differentiate our relatively optimistic view of the economy from that of other economists is that we believe the economic speed limit has accelerated The fourth quarter increase in productivity suggests we are on the right track Faster-than-expected GDP growth and the steady upswing in stock prices are much easier to understand if one is willing to believe that the economy’s potential growth rate has climbed.

Potential growth is a long-term concept. It is an estimate of how quickly the economy can grow when it is at full employment. We do not know exactly what that growth rate is, but we can make an educated guess by adding the growth rate in the labor force to the growth rate of productivity. If we know how many people are working and how productive they are, we can probably figure out how many goods and services they can produce which is what GDP is all about.

In the 1990’s the labor force was growing at a 1.5% pace, productivity rose 2.0%, so the economic speed limit was believed to be 3.5%. And, indeed, the economy grew at that pace for a decade. But today as the baby boomers retire, labor force growth has slowed to 0.8%. Productivity growth has slipped from 2.0% to 1.0%, so the speed limit has downshifted to 1.8%. It is a widespread view. The Fed believes potential growth is 1.8%. The Congressional Budget Office has exactly the same estimate. In contrast, we believe potential growth has already climbed to 2.2% and is likely to soon reach 2.5%.

Both our forecast and that of others incorporate 0.8% growth for the labor force. Thus, the difference between the estimates is centered on the likely growth rate of productivity. Most other economists think that, over the long-haul, productivity will rise 1.0%. We believe it can easily average 1.7%. Technology is boosting worker productivity and with 5-G on the way one can expect an even more robust growth rate in the years to come.

This past week we learned that productivity growth in 2019 averaged 1.8%. But that is a single-year outcome and probably should not be given too much weight in calculating potential growth which is a longer-term concept. Productivity growth in the past three years has averaged 1.4%. If its growth rate has been 1.4% in the past three years and 1.8% last year, it appears that its growth is actually accelerating.

At what point do we conclude that productivity growth has accelerated long enough to boost our long-term estimate? Given its performance over the past three years with growth of 1.4%, we are willing to accept that its longer-term growth rate has accelerated. If we re-do the math and combine 0.8% growth in the labor force with 1.4% growth in productivity, we conclude that potential growth has already quickened to 2.2%. And if last year’s performance is indicative of a further pickup to perhaps 1.7% then potential growth is likely to reach 2.5% within the next year or two (0.8% growth in the labor force plus 1.7% growth in productivity).

Most economists believe that 2019 GDP growth of 2.3% is well in excess of their presumed 1.8% potential growth rate and, therefore, cannot be sustained. We don’t buy it. We suggest that potential growth is 2.2% currently and, hence, 2019 GDP growth is not excessive at all. If productivity growth climbs even more rapidly in the years ahead, our projected GDP growth rates for 2020 and 2021 of 2.4% are equally sustainable.

If the majority of economists cling to the notion that the current pace of economic activity is excessive, they will continue to anticipate a growth slowdown in the years to come. They will dismiss each quarter’s faster-than-expected growth rate as an aberration.

They will also continue to be mystified by the steady run-up in stock prices. GDP growth of 2.5% in the years ahead will undoubtedly produce faster growth in earnings than 1.8% GDP growth.

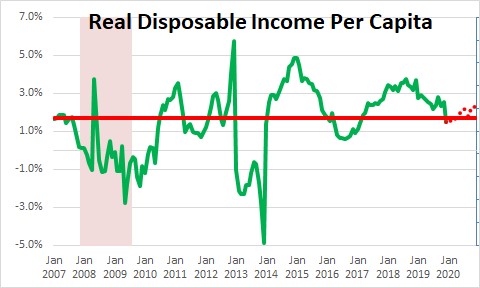

Think, too, about growth in our standard of living. Economists generally use real disposable income per capita as a proxy for growth in our standard of living. If GDP growth (a measure of production) rises 0.7% more rapidly — 2.5% versus 1.8%, then income will also rise 0.7% more quickly. Over the past 25 years our standard of living has risen, on average, 1.6% annually. Going forward that growth rate could easily climb to 2.3%.

Why the faster growth in productivity? Think technology. Big data allows firms to better understand their customers – who they are, where they live, their sex, age, income level. That, in turn, allows them to focus their marketing efforts on those people who are actually likely to buy their products. It lowers costs and probably increases top line growth as well. Business leaders can make smarter decisions.

3-D printing is used today for manufacturing a huge number of products — prosthetic limbs for animals and humans, home construction (think concrete or even glass houses), intricate jewelry, cake decorating, chocolate making, machine tool parts throughout the manufacturing sector, firearms manufacturing, precision musical instruments.

Artificial intelligence is exploding – personal assistants like Siri use machine-learning technology to predict and understand our questions and requests. Autonomously powered self-driving vehicles that sense speed and traffic conditions are already in use. Increasingly powerful search engines allow us to scour the internet for information. Its usage is poised to explode once 5-G becomes widely available.

It seems to us a lot easier to understand what is happening in the economy today if one is willing to accept that potential GDP growth is no longer 1.8% but 2.2% today and headed higher tomorrow

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Stephen,

You are on the right track with the impact of technology. We are just seeing the beginning.

brilliant post!

You have become my mentor! You have been onto tech for ages.

Steve

Thanks Michele. Nice to hear from you! Hope all is well with you and Olivier. I was thinking about you recently. Mary and I were supposed to be on a four week cruise in Asia — which was scheduled to end in Hong Kong. They replaced H.K. with Japan. Then we see cruise ships quarantined in Yokohama harbor. And now I see that the Holland America Westerdam was turned away from Bangkok. Getting quarantined in your cabin for 14 days did not sound like an appetizing end to the trip. And who knows if we would have actually been able to get off the ship in Singapore, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, etc. We pulled the plug and booked the same trip next year. I was thinking about you trying to sell you wine in China and H.K. Are you still focusing on marketing it in the U.S.?

P.S. With our calendars free for an entire month, Mary and quickly booked a cruise through the Galapagos next month. And we are going on a road trip Sunday through the Southeast — St. Augustine, Amelia Island, and Savannah. Not nearly as enticing as Asia, but it will be nice.

All the best.

Steve