November 22, 2019

One of the big themes that triggered the widespread economic angst this year was slower growth overseas and the fear it could spill over into the U.S. and negatively impact growth here as well. The Fed was so spooked it chose to cut the funds rate 0.75% during the summer as an insurance policy to prevent such a thing from occurring. It apparently worked miracles! The stock market is on a roll and has recently set a series of record high levels. Not only that, the same thing is happening to stock markets around the globe. Did the Fed just save the world? We don’t think so. Our explanation is simpler. Tariffs and sanctions impede the pace of economic activity. Everybody loses. But eventually the world adjusts. GDP growth ratchets downward initially. That is what we saw in 2019. But then the drag on growth disappears and GDP growth rebounds. That is what we are going to see in 2020.

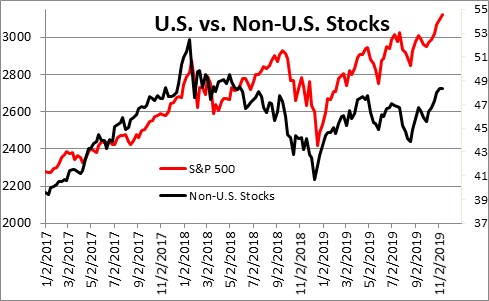

All major U.S. stock market indexes have recently set a series of record high levels. The S&P 500 index has risen 29% since reaching its mid-December 2018 low point. But look what has been happening outside the U.S. In that same period of time the Morgan Stanley All World Index Ex the U.S. has risen 19%. Where is that happening? Think Europe. The Euro Stoxx 50 Index has risen 26%. That is important because the European Union is the United States largest trade partner (if one looks at exports plus imports). Think China, the United States next largest trade partner. Despite the slowdown in GDP growth in China its MCHI Index has climbed 19%. Think Japan. The Nikkei 225 has climbed 17%. It is difficult to imagine that rate cuts in the United States have caused this widespread rebound in global stock prices.

Our sense is that the U.S/China trade war and sanctions are largely responsible for both the initial decline and subsequent rebound of stock prices, as well as the drop-off in GDP growth in 2019 and its likely rebound in 2020. While talked about for some time, the first shot occurred in April 2018 when Trump imposed tariffs on all steel and aluminum imports. It quickly escalated as tit-for-tat tariff hikes occurred between the U.S. and China through May of this year. Given that GDP growth has slowed in both countries and elsewhere, China and the United States currently have a strong incentive to reach some sort of trade accord. At the moment there are hints from both sides that a deal could be reached by December 15. The tariffs scheduled to go into effect on that date were initially set for early November but were postponed. It is hard to know what is likely to happen between now and then because of political posturing by both sides.

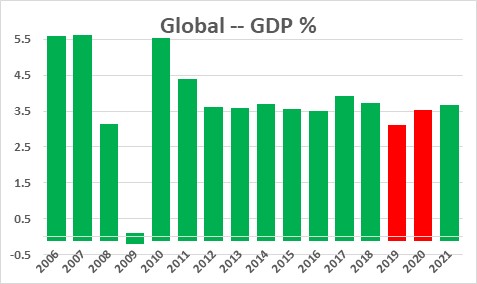

But what is clear is that trade has taken a toll on GDP growth around the world. At the same time, sanctions imposed by Trump on Venezuela and Iran have clobbered GDP growth in those two countries. The IMF estimates that global GDP growth slowed from 3.6% in 2018 to 3.0% this year. That outcome was widespread with most countries and regions experiencing growth slowdowns of somewhere between 0.5-1.0%. For example, the IMF estimates GDP growth in the U.S. slowed from 2.9% to 2.4%, Europe slowed from 1.9% to 1.2%. China slipped from 6.6% to 6.1%, emerging economies from 4.5% to 3.9%, the Middle East from 1.9% to 0.9%, and Latin America from 1.0% to 0.2%. The combo of a trade war and sanctions took no prisoners.

But take a look at the IMF’s global growth forecasts for 2020. Growth is expected to rebound from 3.0% in 2019 to 3.4%. How can that be? Our sense is that countries eventually adjust to the new tariff levels (and sanctions), and the initial hit on GDP growth disappears. For example, the IMF expects growth in the United States to edge lower from 2.4% to 2.1%, and growth in China to slip a bit from 6.1% to 5.8%. But elsewhere growth will rebound. Growth in Europe is expected to climb from 1.2% to 1.4%. In the Middle East it looks for a growth to pick up from 0.9% to 2.9% (largely as the result of growth in Iran rebounding from -9.5% to 0.0%), and Latin America from 0.2% to 1.8% (largely as the result of growth in Venezuela going from -35% to -10%. The world does not return to normal. That will not occur until all of the tariffs and sanctions disappear. But, essentially, the initial drag on growth disappears and — along with it — the fear of a global recession.

That, in our opinion, is what is driving the current run-up in stock prices around the globe. There may also be a sniff of some thawing in the U.S./China trade spat. Call it a relief trade if you will. But taking the risk of a global recession off the table and setting the stage for at least some return to normal is a positive for stock markets everywhere and global GDP growth. Removing the negatives is, without a doubt, a good thing.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

I want to celebrate, but the fed threw so much money at the banks I think some of the US markets were improved by them buying assets with the money. Unless the fed continues this, which they may, I don’t know how long the party will continue.

Hi Mike.

Thanks for taking the time to comment. I agree that the banks have almost certainly contributed to the run-up in stock prices. And certainly the stock market never goes in a straight line so we should expect some pullback before long. But that, to me, is nothing more than the normal ebb and flow of stock prices. I believe the most important thing is that the markets expected a worst case scenario which is not going to happen any time soon. That suggests GDP growth next year will be fine. I am anticipating 2.4% U.S. GDP growth in 2020. I think the pack is somewhere at the 2.0% mark or a shade less. As always, we will see.

Steve