June 9, 2017

Most economists believe the labor market is at full employment. However, it is at least possible that it is not yet there. But, however one wants to measure it, it is close and it is steadily tightening with each passing month. Hourly wages have risen less rapidly than expected thus far, but that is likely to change in the months ahead. As that transpires, there should be additional upward pressure on the inflation rate.

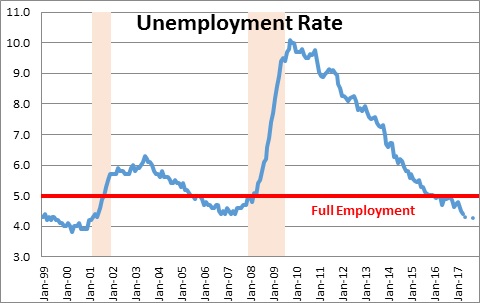

At 4.3% the unemployment rate is below virtually every economist’s estimate of “full employment” which is the point at which everyone who wants a job presumably has one. The Fed believes full employment is between 4.7-5.0%. But full employment is unobservable. Economists have to estimate it. Could it be lower? Sure. As low as 4.0%? It is a long shot, but yes. After all the unemployment rate was at the 4% mark for a long while prior to the 2001 recession with only moderate upward pressure on the core inflation rate.

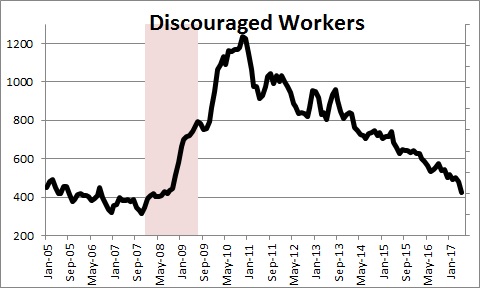

In the past Fed Chair Yellen suggested that the labor market was not at full employment because there were still a large number of “underemployed” workers. There are two types of such workers. First, there are “discouraged workers”. These people would like to have a job but have been out of work so long they have given up looking. As one might expect the number of discouraged workers has been steadily falling and is now essentially where it was prior to the recession.

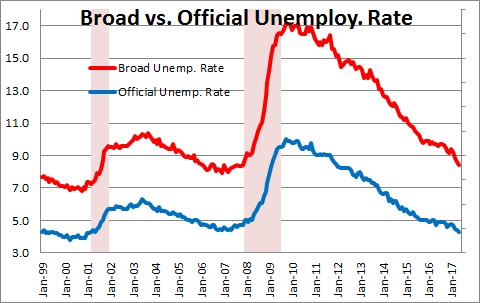

Second, additional workers are currently employed part time but would like full time employment. This series has also been steadily declining but remains somewhat above where it was going into the recession.

Yellen’s preferred measure of unemployment includes both unemployed and underemployed workers. That rate is currently at 8.4% which is lower than the 8.8% it was going into the 2007-2008 recession. However, going into the 2001 recession it was 7.4%. Is the economy at full employment using this broader measure of employment? Maybe. But one can certainly make a plausible case that the full employment threshold for this measure is lower than its current level of 8.4%.

The bottom line is that there is no “magic level” of full employment. Economists make guesses. Most believe the economy is already at full employment, but it is possible that is not the case. However, it is close and getting closer with each passing month.

Economists are so concerned with full employment because, once attained, employers will have increasing difficulty finding an adequate supply of workers. They will ask existing employees to work longer hours. They will require them to work overtime. Eventually they will offer higher wages and/or more attractive benefits to attract the workers they need. But those actions boost labor costs and, eventually, put upward pressure on the inflation rate. All of that is already happening to some degree.

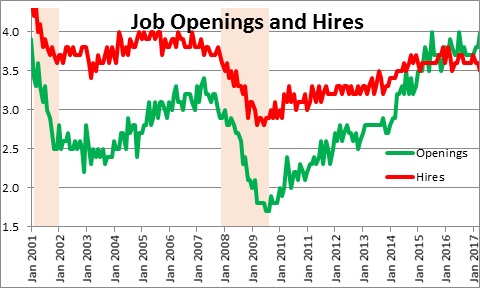

The number of job openings today exceeds the number of hires. That has never happened before. Jobs are available but they remain unfilled. Why? Workers may not have the appropriate skills. Many may not be able to pass drug tests. Others may be content to receive welfare benefits and are unwilling to work. Whatever the case, jobs are available and employers are unable to fill them.

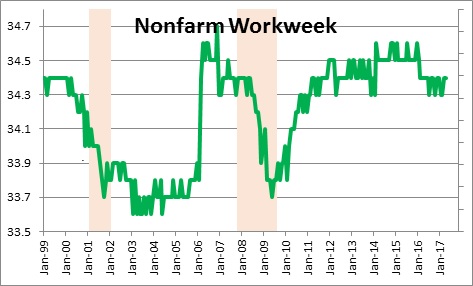

The nonfarm workweek is already quite long. There is little room for employers to further lengthen the workweek to boost output. They need bodies.

That is particularly true in the manufacturing sector where at 40.7 hours the workweek is far longer than the 40.0 hour workweek that prevailed prior to the recession. Factory officials may be asking their employees to work longer hours because they cannot find enough qualified workers.

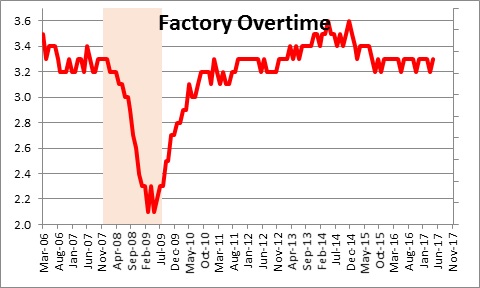

Overtime hours are also quite high. Factory owners are running out of options to boost output. They need more workers and will have to pay up to get them.

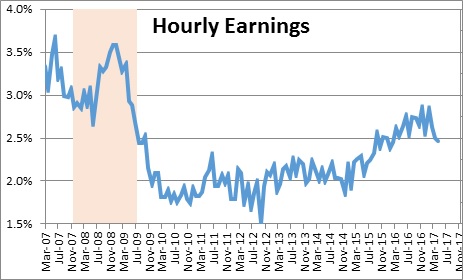

As labor demand intensifies one should expect wage rates to accelerate and that is the case. They had been climbing steadily at a 2.0% rate a few years ago, but have recently climbed into a range from 2.5-2.8%.

After a first quarter slump the economy appears to be re-accelerating. That will create jobs and all measures of the unemployment rate will fall further. As unemployment rates decline wage pressures will intensify.

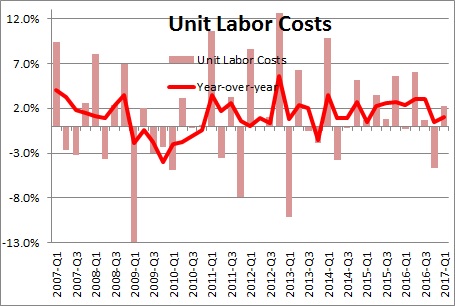

The final piece of the puzzle has to do with productivity gains and “unit labor costs”. If wages rise 3% and workers are 3% more productive, employers do not care. They are getting 3% more output. Labor costs adjusted for productivity are known as “unit labor costs”. This is the relevant metric for measuring the upward pressure on the inflation rate caused by tightness in the labor market. Thus far, unit labor costs are rising at a 1.0% pace which is perfectly consistent with the Fed’s 2.0% inflation target. But will unit labor costs remain benign? Probably not.

Whether the economy has reached full employment or not, it is close and labor costs will be steadily picking up. Can productivity keep pace? That may be more challenging. As we see it, the direction for labor costs and inflation is clear. They are going to accelerate but the speed of ascent has yet to be determined, and that is critical for determining how quickly the Fed will need to raise interest rates in the months ahead.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me