December 3, 2021

The November employment report was both surprising and revealing. Payroll employment rose by 210 thousand which was far smaller than the 550 thousand gain that had been expected. Some economists suggest that outcome is a sign of emerging weakness in the economy. Not so. Civilian employment – which is the measure of employment used in calculating the unemployment rate – rose by an astonishing 1,136 thousand. This latter employment measure includes not only people who are on a company’s payroll but also self-employed workers. While there is always noise between the two surveys on a month-to-month basis, they tend to grow at roughly the same pace over time. But no longer. In the 19 months since the recession ended payroll employment has risen by 18.5 million workers while civilian employment has climbed by 21.8 million. The implication is that self-employed workers have risen 3.5 million since the end of the recession. Having lost their job during the pandemic workers are no longer willing to tolerate company-imposed rules, long hours, a long commute, a sometimes hostile work environment, and low pay while their bosses get rich. This is a sea change in the nature of the labor market. Employers will have to work much harder to attract the workers they need. Higher wages may help, but working conditions will have to be altered as well. Employers are going to have to become creative. The game has changed.

There have always been two measures of employment with most attention on payroll employment. That is because it is reported by companies and is generally considered to be more accurate. Civilian employment is used in calculating the unemployment rate. It is derived from a survey conducted by government workers knocking on doors and asking people whether they are employed. But many people are fearful of someone from the government asking about their employment status and their responses may not always be truthful. Thus, the civilian employment data are generally regarded as less accurate than the payroll measure When analyzing the employment data the focus has always been on payroll employment.

But the November outcome with payroll employment rising 210 thousand while civilian employment jumped by 1,136 thousand cannot be ignored. This is not just a monthly wiggle. Since the recession ended in April of last year payroll employment has risen by 18,450 thousand. Civilian employment, which includes self-employed workers, has risen by 21,805 thousand. Thus, it appears that the number of self-employed workers has risen by perhaps 3.5 million workers in the 19 months since the recession ended. People seem to be tired of working for somebody else in a sometimes dirty or hostile work environment, a long commute, and being underpaid while their bosses get rich. The pandemic has revolutionized the labor market.

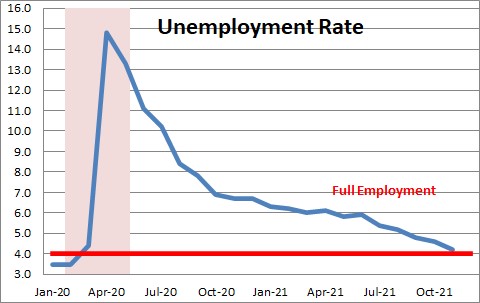

It is tempting to conclude that the smaller-than-expected increase in the unemployment rate is a sign that the labor market is no longer improving rapidly. That would be a serious mistake. What economists have been missing is that so many people are now willing to venture out on their own. In November the labor force rose 594 thousand while employment surged by 1,136 thousand. As a result the number of unemployed workers fell by 542 thousand and the unemployment rate sank 0.4% to 4.2%. This is the fifth consecutive decline in the unemployment rate. In June the unemployment rate was 5.9%. In the five months since it has declined by 0.5%, 0.2%, 0.4%, 0.2%, and 0.4% and now stands at 4.2%. The Fed believes that full employment, the point at which everybody who wants a job has one, is 4.0%. We are there.

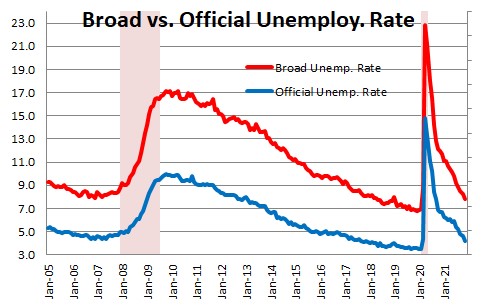

Some economists suggest that some people are so discouraged that they have given up looking for employment. Others are working a part-time job when they would really like full-time employment. These people are captured in a broader measure of employment which has also been falling like a rock and now stands at 7.8%. There is no official “full-employment” threshold for this particular measure of the unemployment rate, but prior to each of the past three recessions this measure has been around the 8.0% mark. This broader unemployment measure is also at full employment.

This surge in self-employment perhaps explains why the record number of job openings is so high. Workers prefer not to work for somebody else. They are becoming entrepreneurs and striking out on their own. Employers are going to have to work harder to attract new employees.

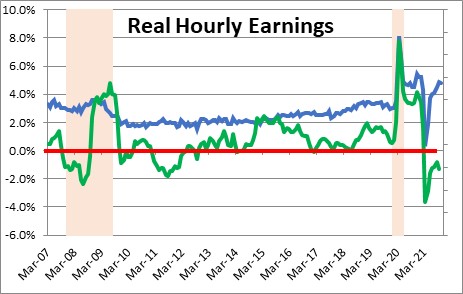

They are almost certainly going to have to offer far more attractive wages. In the past year average hourly earnings have risen 4.8%. But, unfortunately, inflation has risen even faster and real or inflation-adjusted earnings have declined 1.3% and workers have noticed. It seems likely that in the months ahead workers and unions have the leverage to demand higher wages. And employers are easily able to pass along these higher costs to their customers. Thus, that the inflation rate is almost certain to remain elevated.

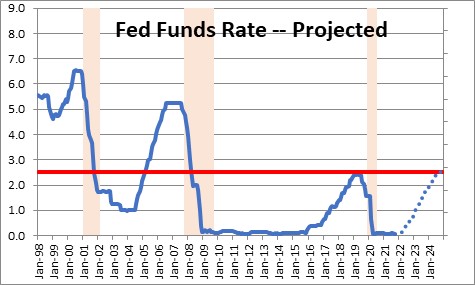

How will the Fed respond to this? Powell has indicated that it is no longer appropriate to use the term “temporary” to explain the rather pronounced increase in the inflation rate. It’s about time. He suggested that the Fed will “taper” its purchases of securities more quickly than it had indicated previously. That probably means they will eliminate further purchases of U.S. Treasury securities by March rather than June. But what is really needed are higher rates. The inflation rate is not going to come down until such time as the Fed gets serious about adopting a more neutral policy stance. The Fed has said that a “neutral” funds rate is 2.5%. Once it starts raising rates it typically moves about 0.25% per quarter. That means it will take 10 quarters for the funds rate from its current level of 0.0% to a neutral level of 2.5%. This means that the Fed’s monetary policy stance will remain stimulative for almost three more years. Really? The Fed is not even close to becoming serious about slowing the rate of inflation.

The pandemic-triggered lockdown in March and April of last year has completely transformed the U.S. economy. Twenty-two million workers lost their job and had to start working from home. Firms had to rapidly embrace technology to stay in business. They remain unable get the materials they need. They economy is still adapting to this new economic environment and those changes are no more apparent than in the labor market. Stay tuned it is going to be a wild ride.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Insightful article as usual. Love the headline on this one! 😃

Hi Michele,

Around here in Charleston SC the number of new businesses being formed is off the charts. Something different seems to be going on.

Hope all is well. Enjoy the holidays.

Steve

Couldn’t resist the headline!

headline was. classic

May have gotten a bit carried away with that one — but I couldn’t resist.