June 28, 2019

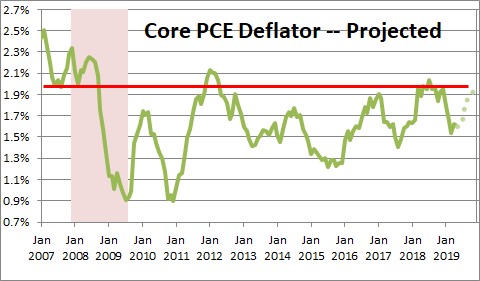

The Fed is split almost equally into two camps. One group expects no change in rates between now and yearend. The competing group expects a 0.5% rate reduction. As we see it, the economy is chugging along at an acceptable pace and while inflation is running a bit below the Fed’s 2.0% target it is likely to approach the target by yearend. There is, therefore, no need for lower rates. The lower rates group bases its view largely on the persistent shortfall in inflation and how best to get it back on track.

The President of the Minneapolis Fed, Neel Kashkari, has been advocating a 0.5% cut in rates for some time. He made a speech last week that clearly laid out his case. It is an interesting read.

He notes that the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge has been below target for almost a decade. If the Fed is going to have an inflation target then it needs to make a credible effort to reach that target. Thus far it has treated its 2.0% inflation target more as a ceiling rather than a symmetric target. It may be time to address that issue and get inflation back on track.

Kashkari believes that the Fed should cut rates 0.5% today and pledge not to raise rates again until the core inflation rate reaches the Fed’s 2.0% target on a sustained basis. The increased focus on inflation is a very different way of thinking for the Fed. Given that seven FOMC members currently support a 0.5% cut in rates between now and yearend, the view seems to be gaining traction.

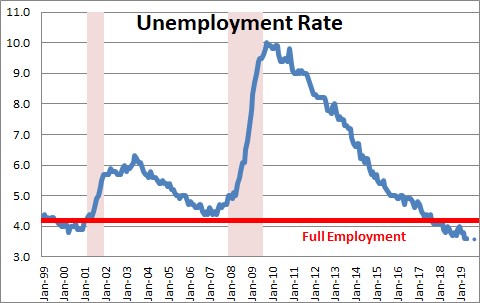

One of the key tenets of his case is that even though the unemployment rate is at 3.6% the economy may still not have achieved full employment.

Economists do not know exactly what that threshold level is. A few years ago economists thought it was 5.0%. Then it became 4.5%. The Fed currently thinks it has slipped to 4.2%. Kashkari has suggested it might be 3.5% — or lower.

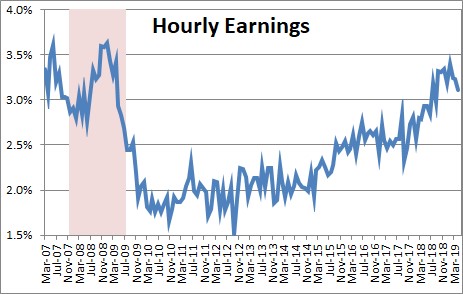

When the labor market approaches full employment employers must bid more aggressively to get the workers they need and wages begin to climb. Thus, rising wages are an indication that the labor market is approaching full employment. Given that average hourly earnings have accelerated from 2.0% a couple of years ago to 3.2% today, most economists believe the labor market has already reached full employment. Once that happens the higher labor costs should cause firms to raise prices and inflation will climb. But that has not happened.

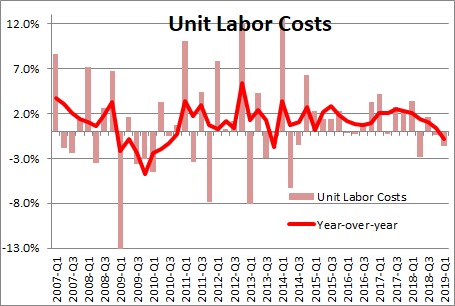

We have said many times that upward pressure on the inflation rate should not be gauged by the faster growth in average hourly earnings because higher wages can be offset if workers are more productive. If, for example, a firm pays its workers 3.0% higher wages because they are 3.0% more productive there is no reason to raise prices. Thus, the upward pressure on inflation should be measured by the increase in labor costs adjusted for the change in productivity. Economists call this measure “unit labor costs”. In the past year worker compensation (wages plus benefits) has risen 1.5%. Productivity has risen 2.4%. Thus, unit labor costs have declined 0.8%. Perhaps Kashkari is right and the labor market is not as tight as what is generally perceived. If it were, firms would be boosting worker compensation more quickly than they are currently.

Unit labor costs consist of two numbers – the growth rate in compensation and the growth rate for productivity. The Fed thinks that over the longer haul productivity will average about 1.0%. To reach 2.0% growth in unit labor costs, compensation must rise by 3.0%. We think productivity growth going forward will average 2.0%. In our world compensation growth of 4.0% is required to get unit labor costs to rise 2.0%. So, for unit labor costs to rise by 2.0%, compensation must climb somewhere between 3.0% and 4.0% versus 1.5% today. If unit labor costs climb by 2.0%, the inflation rate is likely to follow.

While the economy probably does not need lower rates to keep GDP growth humming along at a rate somewhere between 2.0-2.5%, it could need lower rates if – for the first time — the Fed is seriously going to focus on pushing the inflation rate meaningfully higher.

What are the benefits? Lower rates would test the limit regarding the full employment threshold of the unemployment rate. Could it be 3.5%? Could it be even lower?

Keep in mind that the unemployment rate for blacks today is 6.2%. For Asians it is 4.2%. Would lower rates reduce the unemployment rates for those two groups?

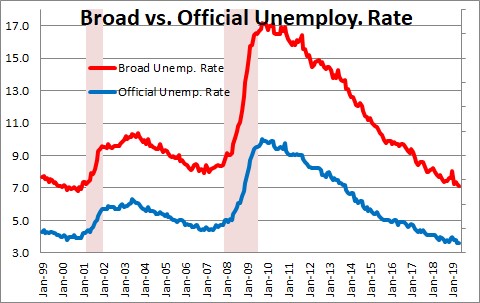

The broader measure of the unemployment rate today is 7.1% versus the official rate of 3.6%. The difference between the two represents 1.4 million workers who are not currently looking for employment. Would lower rates bring about higher wages and thereby entice some of those marginally employed workers to seek employment? At this point nobody knows the answer to these questions.

What is the risk? Could inflation suddenly begin to climb rapidly? Probably not. Measures of inflation expectations over the next 10 years seem to have dropped recently to 1.6%. The Fed has done a great job of convincing everyone that inflation will remain low. Changing those expectations will take time. Meanwhile, inflation in Europe, the U.K., and Japan are all in a range between 1.0- 2.0%. The U.S. is unlikely to experience a surge of inflation if inflation remains low elsewhere. Given that a pickup in inflation may take some time to produce, Kashkari believes that the Fed should not seek a level of the funds rate that is “neutral”, but lower rates to a point that will clearly stimulate the economy. If inflation should pick up quickly and breech the 2.0% mark the Fed could easily raise rates to slow things down.

We are not quite ready to jump on board with the Kashkari game plan. But technology has fundamentally altered the U.S. economy. Productivity growth has climbed. The economy’s speed limit seems to be rising. Inflation is lower than desired because goods producing firms have lost all ability to raise prices. The world is different. Given this new economic environment perhaps the way monetary policy is conducted needs to be changed as well. Food for thought.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

What I find interesting about the trend of productivity washing away increased costs of labor is the importance for companies (especially manufacturing and services) to keep up with improved productivity through technology and good old leadership and management. It looks like this trend will continue for some time and any company who does not keep up will find out that they may not be able to be competitive in the future.

HI Mike,

Thanks for your note. I agree that productivity is likely to climb at a reasonably rapid rate for some time to come. If employers cannot find enough workers they will turn to technology to boost output. When I think of “investment spending” I typically think of spending on building new plants and more efficient equipment, but there is a third part — intellectual property which is where all the spending on software shows up. It is currently growing at a double-digit pace. That is the fastest growth rate since 2000. It makes me think I am on the right track thinking that productivity will continue to climb. If that is true, our economic speed limit should climb from 2.0% to perhaps the 2.8% I am looking for. And from the firm’s viewpoint they can increase output and even lower costs a bit. Sounds good to me!

All the best.

Steve