June 6, 2014

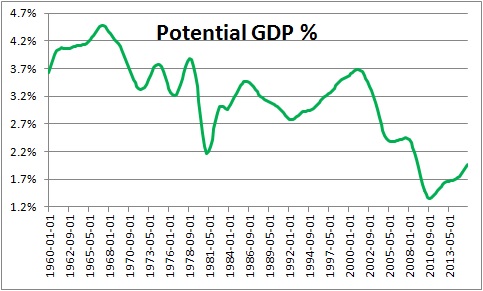

In the early 2000’s potential GDP growth — the economy’s speed limit — was about 3.5%. Today that potential pace is no more than 2.0%. Why the slippage? What does it mean?

Potential growth is a function of two variables – growth in the labor force, and growth in productivity. In the early 2000’s the workforce was growing by about 1.5%, productivity was rising by about 2.0%. Add the two numbers together and potential growth was about 3.5%.

Today the comparable numbers are 0.5% for growth in the labor force and 1.5% growth in productivity which implies potential growth of only 2.0%. What happened?

Labor Force. The labor force is growing more slowly today for a couple of reasons. First, population growth has been reduced in part because of a slowdown in immigration – both legal and illegal. Security concerns in the wake of 9/11 have made it more difficult for foreigners to enter the U.S. legally. At the same time heightened border security has sharply curtailed illegal immigration.

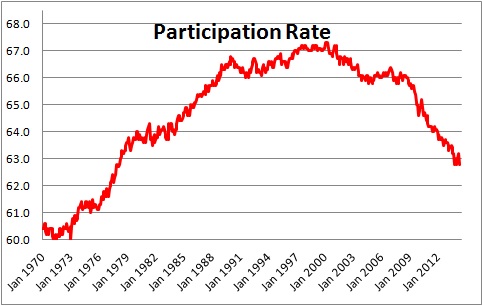

Labor force growth has also slowed because the baby boomers are retiring. When they entered the labor force in 1970’s and 1980’s the participation rate – the percent of the population that was looking for employment – rose sharply. As the baby boomers retire the participation rate will go the other direction.

Between slower growth in population and a lower participation rate, it is likely that the labor force will grow only 0.5% annually between now and the end of the decade.

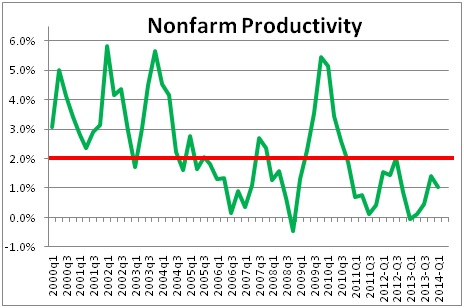

Productivity. The other part of the equation for potential GDP is growth in productivity. From 2000 to 2013 productivity climbed 2.0% per year. It grew very rapidly early on but has since slowed. A large part productivity growth between 2000-2005 was attributable to the spending boom on technology in the 1990’s which gave workers access to computing equipment that allowed them to do their jobs much more efficiently. But such spending was curtailed initially by the recession. Since the recession ended in mid-2009 firms have been reluctant to boost spending on research and development in part because the computing industry has not been innovating as quickly as it did in the past. For that reason productivity growth will average about 1.5% going forward versus 2.0% fourteen years ago.

Combining 0.5% growth in the labor force with 1.5% growth in productivity suggests that potential growth is now about 2.0% compared to 3.5% previously.

This has several important implications. First, we should expect GDP growth to average only about 2.0% a year going forward rather than the 3.5% pace we experienced in the 1990’s and the early 2000’s.

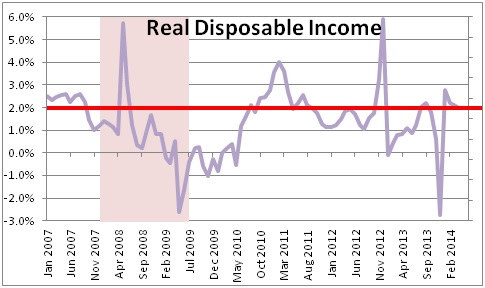

Second, slower potential growth implies that income will also grow more slowly. Real income should grow at about the same 2.0% pace as production. Indeed, real income is currently growing by 2.0%. While many expect income growth to quicken, it may not.

Third, slower potential growth suggests that equilibrium interest rates may also be somewhat lower than had been believed previously. In theory the equilibrium funds rate should be roughly in line with nominal GDP growth or, in this case, 4.0% — 2.0% GDP growth and 2.0% inflation. And, indeed, that is the consensus view at the Fed. However, at the beginning of the year the majority of FOMC officials thought the equilibrium funds rate was about 4.25%. Some Fed officials apparently think that potential GDP growth could be even lower and they suggest that the equilibrium funds rate might be 3.5-3.75%.

Long-term interest rates are partially determined by the funds rate but also by some risk premium Historically, the yield on the Treasury’s 10-year note has averaged 1.6% higher than the funds rate. Hence, if one believes the equilibrium funds rate is 4.0% the yield on the 10-year note should be about 5.6%. If one believes the equilibrium funds rate is lower, then the yield on the 10-year note may be closer to 5.0%.

The bottom line is that the economy simply cannot grow as rapidly today as it did in the past. It can safely grow more quickly than its 2.0% potential pace for a while longer because there continues to be some slack in the economy. Over time, however, we should expect GDP growth to average 2.0% rather than 3.5%. Income should climb at roughly that same 2.0% pace. The good news is that equilibrium short and long-term interest rates may be a bit lower than had been expected previously. The post-recession world has changed just a little bit.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, SC

Follow Me