March 11, 2015

All eyes this week will be on the outcome of the Fed’s Open Market Committee meeting. The Fed will likely boost the funds rate from 0.0% to 0.25%. That is the initial step of a much longer two-step process. First, the Fed must decide how quickly and by how much it intends to boost short-term interest rates. Second, it must shrink its currently bloated balance sheet to eliminate excess liquidity from the economy. The policy statement released at the end of the meeting will say that it intends do everything it can to bring inflation back down to the 2.0% objective quickly. But the reality is that its current policy is so far out of whack that it will take years to achieve that objective.

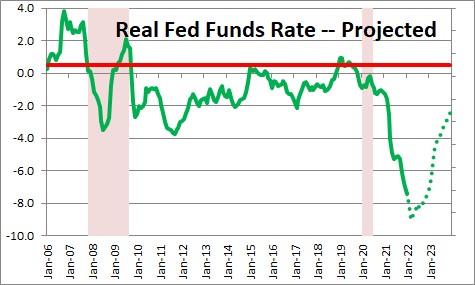

The Fed believes the funds rate is “neutral”, i.e. neither stimulating nor retarding the pace of economic activity, when it is about 2.5%. But the appropriate level of the funds rate is determined by the “real” or inflation-adjusted rate. Through periods of Fed tightening, easing, and neutrality since 2000 the real rate averaged 0.5%. Thus the Fed has concluded that its policy is “neutral” when the funds rate is about 0.5% above its 2.0% inflation target, or 2.5%.

The problem is that the inflation rate is not even remotely close to 2.0%. In the past year the CPI has risen 7.9%. With the funds rate currently at 0.0%, the real rate today is negative, -7.9%. If the Fed raises the funds rate 0.25% at every FOMC meeting this year and next, the funds rate will be 3.75% at the end of 2023. But we expect the CPI to increase 6.2% in 2023. That means that at the end of 2023 the real funds rate will be -2.5%. That is not even close to a neutral real rate of 0.5%. if the Fed thinks it is going to slow the rate of economic activity with a sharply negative real funds rate it is fooling itself. In the double-digit inflationary period of 1979-80 the real rate climbed to 8.0% — a funds rate of 19.0% with an inflation rate of 11.0%. That is what was needed to convince people that it was serious about breaking the double-digit rate of inflation. As another example, prior to the 2008-09 recession the real rate was 3.0%. The real rate may not need to rise quite as much today, but the point should be that a -2.5% real rate at the end of 2023 is NOT EVEN CLOSE to where it should be and, as a result, the pace of economic activity is not going to slow much..

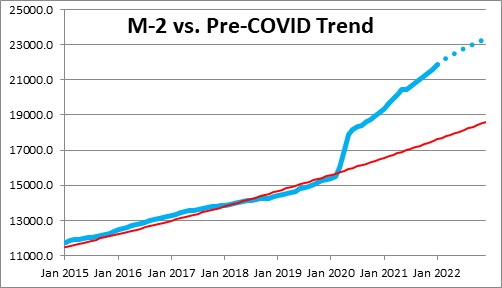

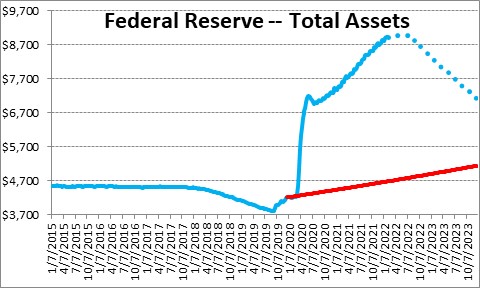

The second part of Fed policy is to control the rate of growth of the money supply. For years the M-2 measure of money grew at a steady rate of 6.0% which is roughly in line with the growth rate of nominal GDP. But from March to May 2020, when the economy was shut down because of the pandemic, the Fed bought $3.0 trillion of U.S. Treasury and mortgage-backed securities and money supply growth skyrocketed to ensure that the economy had sufficient liquidity during the recession. It has continued to buy securities every month since. As a result, the money supply is now $4.2 trillion higher than its long-term growth path. That represents the amount of surplus liquidity in the economy. No wonder the inflation rate is so high!

What that means is that the Fed needs to shrink its balance sheet by $4.2 trillion. That is not going to happen any time soon. At its meeting next week the Fed may indicate a plan to shrink its balance sheet, probably starting in July, by about $100 million per month by letting securities mature and not replace them. If so, by the end of 2023 its portfolio would have shrunk by $1.8 trillion, but the economy will still have more than $2.0 trillion of surplus liquidity at the end of that year.

Through a combination of rate hikes and balance sheet shrinkage, the Fed certainly has the ability to bring its policy into line with where it should be much more quickly than described above. But it cannot have it both ways. It cannot be slow and gradual in its policy adjustment and expect to see the inflation rate return to its 2.0% target any time in the foreseeable future.

In our opinion, the seeds of the next recession have already been sown. The odds of the Fed achieving a soft landing and having the economy slow by just the right amount to curtail inflation without dumping it into recession are very low. Almost invariably the Fed goes too far and the economy slips over the edge. However, for a recession to actually materialize the Fed needs to become much more aggressive. With negative real rates for the foreseeable future, that is unlikely to happen any time soon.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me