March 24, 2023

The Federal Reserve as an institution will never say it expects a recession. But Fed governors and Federal Reserve Bank presidents individually may have that expectation. That seems to be the case at the moment. This past week we learned more about how these Fed officials see the path for the economy, inflation, the unemployment rate and the federal funds rate for the rest of this year. Following a respectable GDP growth rate in the first quarter and most likely the second quarter as well, the Fed looks for a recession in the second half of the year. A recession will lift the unemployment rate from 3.6% currently to 4.5% which is above the full employment threshold of 4.0%. The core inflation rate will slow to 3.6% by December. But because that inflation rate will remain well above the Fed’s 2.0% inflation target these Fed officials do not expect to cut the funds rate in 2023. This is in sharp contrast to the market’s expectation that the funds rate will decline to 4.0% by yearend. Almost everybody expects a second half recession, a significant drop in the inflation rate by yearend and, with the sole exception of the Federal Reserve, a significant decline in the funds rate. We are not yet prepared to buy into this scenario.

But let’s be absolutely clear about one thing. Nobody knows right now what the fallout is likely be from the recent banking crisis. We are all guessing. Furthermore, we are not going to get a decent handle on the consequences for some time. Probably not until midyear. The banking problem began in late March. We could get a few hints of the difficulty in April, but a more complete picture may not emerge until May. But the May data are not released until June. So prepare for another prolonged period of uncertainty and continuing market volatility.

We are concerned that with everyone leaning so far in one direction, the surprise could be that the economy holds up better than expected, the labor market does not weaken substantially, and/or the inflation rate does not shrink as quickly as anticipated.

Once a quarter the Fed governors and Reserve Bank presidents present their economic forecasts for the next several years. This past week these Fed leaders expect GDP growth in 2023 of 0.4%. But first quarter growth is shaping up as something around the 2.0% mark. With the economy still having considerable momentum, second quarter growth should also be positive. We expect it to be 1.0%. The only way growth for the year can average 0.4% is if growth then declines 0.7% in both the third and fourth quarters. We do not know the pattern of growth the Fed has in mind, but it appears that Fed leaders, individually, are expecting a second half recession. These people believe that the fallout from the banking crisis will quickly curtail the availability of credit and push the economy over the edge into recession. It is a perfectly logical story and could be accurate. But for it to occur the fallout from the current banking crisis has to be substantial, businesses must begin to lay off workers so that the unemployment rate rises from 3.6% currently to 4.5% by yearend, and the core PCE inflation rate must fall from 4.7% currently to 3.6%. While that could happen, we remain unconvinced. We continue to believe that the Fed will need to raise the funds rate further, perhaps to the 6.0% mark, for the long-awaited recession to materialize. But right now, given the uncertainty, nobody has a lock on truth — not the Fed and not any private sector economist – including us. Consider the following.

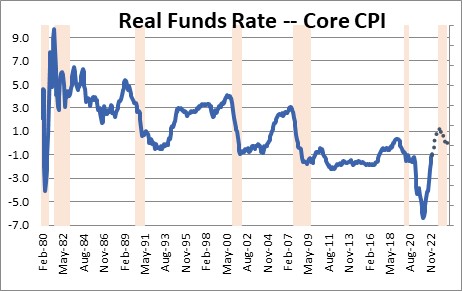

Given the rapid pace of Fed tightening since March of last year everybody has been expecting growth to slow. But yet GDP growth in the third quarter of last year came in at 3.2%. Fourth quarter growth defied expectations and was 2.7%. First quarter growth for this year was initially expected to be about 0.5%. Now, the latest data point towards a 2.0% pace. GDP growth has defied expectations and, perhaps, one reason for that is that the level of interest rates is still too low. Today with the funds rate at the 5.0% mark, the core CPI is 5.5%. Thus, the real funds rate continues to be negative and, in the past, a negative real funds rate has been unable to slow to economy by any significant amount and certainly not enough to trigger a recession.

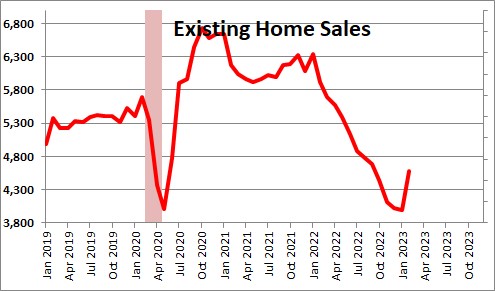

The housing market got crushed in 2020 as rapidly rising house prices and a sharp increase in mortgage rates took its toll. But now mortgage rates have fallen from a peak of 7.0% to 6.5% and seem to be headed lower. At the same time home prices have fallen steadily for the past six months. This combo of events has boosted housing affordability.

As a result, homebuilder confidence has risen and builders have quickened the pace of construction of both single-family homes and apartments. On the demand side, some potential home buyers are back in the game. Both existing and new home sales have begun to climb. Nobody expected this to happen, but it did.

Despite everyone’s expectation the economy still seems to have considerable momentum. Without a doubt the recent banking crisis will reduce the availability of credit for both businesses and consumers which will slow the economy. But slow it from what, to what? Will it be enough to push the economy over the edge in recession?

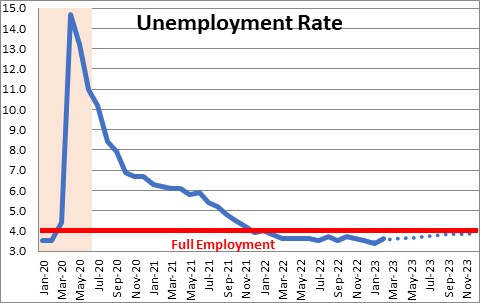

Then there is the unemployment rate. It refuses to climb. Firms remain reluctant to lay off workers for fear of not being able to get them back when they are needed. In the wake of recent events, will that continue to be the case? The Fed believes the unemployment rate will climb from 3.6% currently to 4.5% by the end of the year. We expect it to rise to 4.0%. If we are right the Fed will continue to worry about wage pressures putting upward pressure on the inflation rate.

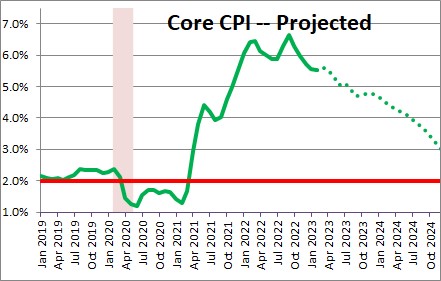

Finally, there is the inflation rate. It has clearly slowed, but it appears to be declining slowly. After reaching a peak of 6.6% in September it has backtracked to 5.5%. But the Fed thinks it is going to plunge to 3.6% by the end of the year. Good luck with that!

The inflation stickiness seems to be associated with the housing component. What goes into the calculation of the CPI is rents. Rents respond to the change in home prices with a lag of about a year. Right now rents are rising rapidly. They have risen 8.1% in the past year. They should begin to fall by midyear, but will they fall quickly enough for the overall index to slow to the extent the Fed expects? We doubt it. Rents are extremely important because they represent one-third of the entire index.

Everybody seems to be expecting a recession, reduced inflation, and lower interest rates by the end of the year. But for that to happen the economy has to be severely hampered by fallout from the banking crisis, the unemployment rate has to rise sharply, and inflation has fall much more quickly. All three of these must happen for the Fed to release the reins on the economy and let the funds rate fall. Anything can happen and perhaps this is the correct view of the world. We are not so sure.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me