February 4, 2022

The January employment report was full of surprises all of which lead to the conclusion that the labor market is extremely tight and the Fed is far behind the curve. Payroll employment rose markedly in January. But COVID and bad weather were supposed to leave employment relatively unchanged. Not only that, the November and December job gains were revised upward dramatically. In addition, more than one million workers who had previously given up looking for a job suddenly began to seek employment and, miraculously, almost all of them found jobs. Given the tightness in the labor market employees are demanding, and getting higher wages. And firms seem easily able to pass them on to their customers. That is bad news on the inflation front. Now the Fed must convince investors that it is serious about hitting its 2.0% inflation target sometime in the foreseeable future. It is time for it to become serious.

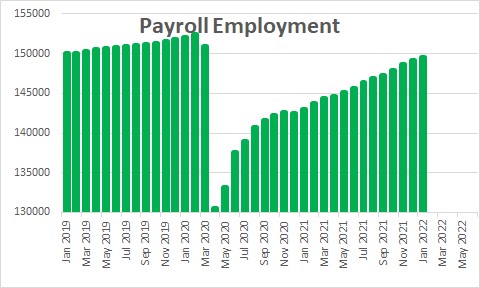

Payroll employment rose 467 thousand in January. That is impressive given that COVID cases were rising rapidly and most of the Northern half of the country was blanketed by snow and ice storms. But even more surprising were the upward revisions to earlier months. For example, payroll employment in November had registered a gain of 249 thousand. But now it rose 697 thousand in that month. Ditto for December. It initially rose 199 thousand. It now shows a gain of 510 thousand. The only way the economy can crank out that number of jobs is if it is growing rapidly. Job openings are at a record high level and, at last, it looks like employers are filling at least some of them.

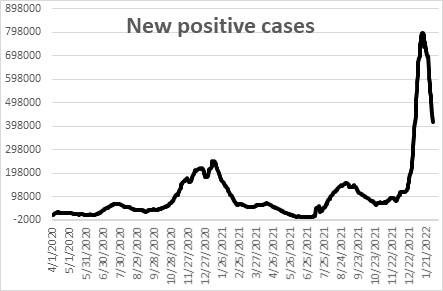

The only soft part of the employment report was that the nonfarm workweek declined 0.2 hour in January after falling 0.1 hour in December. Clearly that weakens the labor market situation – but only for January. But why did the workweek decline? It is abundantly clear – given the extent of job openings – that these recent declines will prove to be temporary.

The shorter workweek in both months was almost certainly attributable to the combination of sharply rising COVID cases and the miserable weather. But the number of new COVID cases has fallen 50% since mid-January and eventually the weather will return to normal. Once that happens, the workweek will rebound to its earlier level. We may be seeing a bit of winter weakness, but spring is just around the corner.

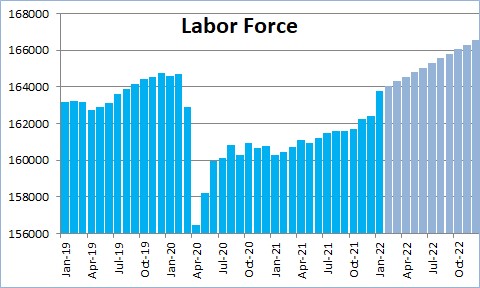

Another remarkable part of the employment report is that the labor force surged by 1.4 million workers in January. To put that in context, the labor force rose by 1.6 million workers in all of 2021. Suddenly, people who had given up looking for employment following the 2020 recession decided it was time to look for a job. That is helpful because it will make employers task of finding able bodied workers somewhat easier, but the tightness in the labor market is extreme and workers are demanding — and getting — higher wages.

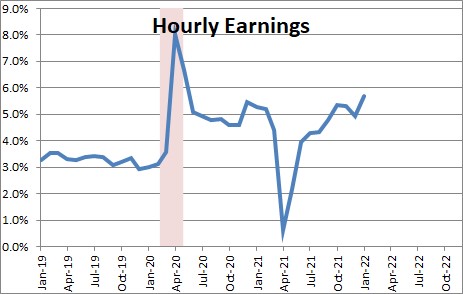

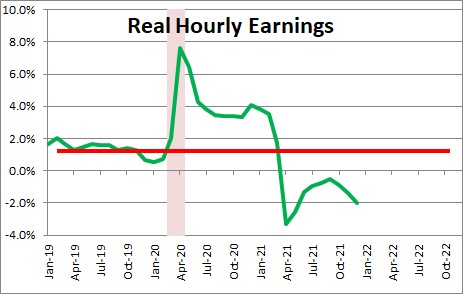

Average hourly earnings jumped by 0.7% in January after rising 0.4% in November and 0.5% in December. In the past year earnings have climbed 5.7%. In the decade from 2010 to 2020 earnings rose on average 2.7% annually. Thus, the 5.7% wage jump in the past year is both impressive – and worrisome. Even worse, in the most recent three-month period earnings have climbed at a breathtaking 6.7% rate. Any way you slice it, earnings are surging.

But while nominal wages may have risen 5.7% in the past year, inflation has climbed by 7.7%. Thus, worker paychecks in real terms have declined 2.0% in the past year. No wonder they are seeking big pay hikes!

All of this is making the Fed’s position worse. The wage situation is a problem because about two-thirds of any firm’s overall cost is labor. Thus, the tightness in the labor market is a huge problem for the Fed and its outlook for inflation.

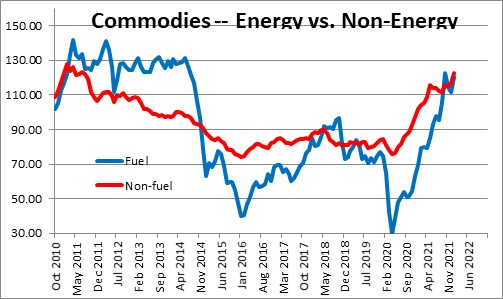

But the inflation run-up is more than labor costs. Commodity prices are surging and it is not just oil. It is both energy and nonenergy commodities. Crude oil prices have jumped to $92 per barrel. And the non-energy price gains are widespread — food, industrial metals, and precious metals. These prices are the highest they have been in a decade.

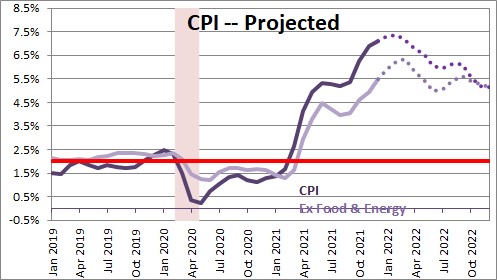

For the Fed there is no silver lining in any of this. It has allowed the funds rate to sink seven percentage points below the inflation rate. Over time the funds rate averages about 0.5% above the inflation rate. Do the math. The Fed is far behind the curve. The Fed thinks that the funds rate is neutral when the funds rate is 2.5%. But in today’s world a 2.5% nominal funds rate is still a negative 4.5% real rate. To slow this down the Fed needs the funds rate to be at roughly the 7.0% mark.

The Fed needs to be bold. In the 1970’s when inflation was soaring the Fed was constantly behind the curve. It would raise the funds rate a little bit, but the inflation rate would rise just as quickly and the Fed never caught up – until Volcker. At one point he raised the funds rate 1.0% per week for four consecutive weeks. Does the group at the Fed today have the courage to do anything even remotely similar? We doubt it. We currently expect seven 0.25% rate hikes in 2022. That would lift the funds rate to 1.75% by yearend. Not even close to where it should be. We hope that at the March 15-16 FOMC meeting the Fed boosts the funds rate by at least 0.5% and lays out a roadmap that puts it far higher than 1.75% by yearend. At the same time it should start aggressively shrinking its bond holdings by, say, $200 million per month. Inflation is headed higher – perhaps much higher – unless the Fed comes up with a new game plan. It has to convince investors that inflation has a chance of returning to the 2.0% mark some time soon. At the moment the expected inflation rate for the next 10 years (as measured by the difference between the nominal and inflation-adjusted 10-year rates) is 2.4%. But it will not stay there unless it can convince the bond market it is serious. We’ll see.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Steve –

In the last paragraph above did you mean $200 billion rather than $200 million?