September 6, 2019

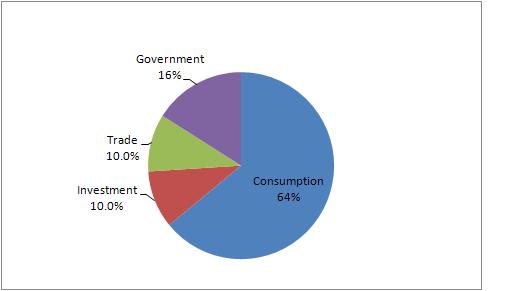

The consensus view is that the tariffs imposed by President Trump have increased the risk of recession in 2020. Even the Federal Reserve seems to buy into that scenario. We continue to disagree with that conclusion for two reasons. First, reduced trade is likely to cut GDP growth next year by a couple tenths of a percent. But the trade sector by itself is too small a portion of the U.S. economy to inflict serious damage on growth, and trade with China is small part of the trade sector. Second, the economic pessimists never talk about consumer spending which is almost 70% of the U.S. economy and consumers continue to spend freely. It is not fair to highlight the weak sectors of the economy without at least mentioning that a far larger portion of the economy is doing just fine.

The argument about trade almost always brings about a reference to the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act that was passed in 1930 which is widely believed to have contributed to the depth of the Great Depression. That bill raised already high tariffs to even higher ones on every imported product from every country. The Economist estimates that the average tariff rate rose from 40% in 1929 to almost 60% in 1932 and, during that same time period, U.S. exports fell 66% and exports by 61%.

But the situation today is not even remotely similar. Initially Trump imposed a relatively broad array of tariffs on goods from Canada, Mexico, and China in particular. But as trade deals were worked out with Canada and Mexico, tariffs imposed on goods from those two countries were subsequently rescinded. Today the tariffs are being imposed on one country – China. Keep in mind that trade today represents about 10% of the U.S. economy, and trade with China is 11% of the 10% or roughly 1% of overall GDP. That is simply not a large enough piece of the pie to seriously curtail growth in the U.S. economy.

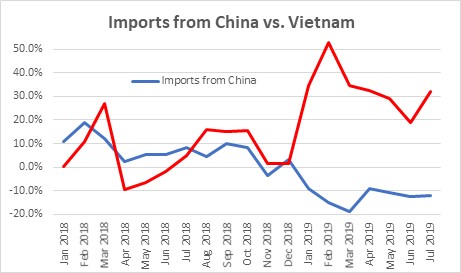

The other interesting thing about trade is that, in response to the tariffs being imposed on goods imported into the U.S. from China, U.S. companies are shifting their production elsewhere, Vietnam in particular. For example, in the past year Chinese imports to the U.S. have fallen by $5.6 billion or 12%. But imports from Vietnam have increased by $1.4 billion or 32%. Vietnam is the most extreme example, but it is not alone. Imports from Taiwan have increased 20%, Japan 9%, South Korea 5%, and India 8%. Thus, it appears that U.S. manufacturers are in the process of shifting production out of China to other countries in Asia. What that means is that while tariffs are having a big negative impact on the Chinese economy, their impact on the U.S. is relatively small. We may be importing fewer goods from China, but importing more goods from other countries in Asia. As we see it, the tariffs imposed on Chinese goods coming into the U.S. will not have a large enough impact on the U.S. economy to reduce GDP growth in any meaningful way.

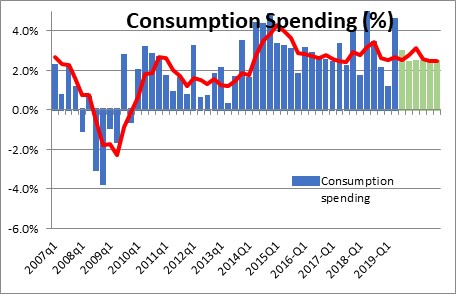

The doomsayers always focus on tariffs and trade. They do not want to talk about the far more important GDP category – consumer spending. As shown in the earlier chart, consumer spending represents almost two-thirds of the U.S. economy, and it continues to do well. Consumer spending rose at a 2.9% pace in the first half of this year, and seems likely to increase at a similar rate in the third quarter. We know, for example, that retail sales jumped 0.7% in July so the quarter is off to a good start, and it has climbed at a 6.2% pace in the past three months. No sign of a slowdown from these data.

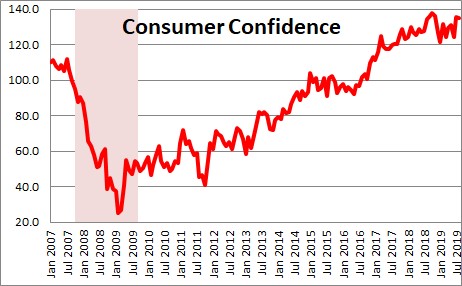

In our opinion, this is no great surprise. Consumers feel good. Confidence is essentially at a 15-year high. Manufacturers’ confidence has been negatively impacted by the tariffs, but the consumer has hardly noticed. Some of this lofty level of confidence is associated with the stock market which is now within 1.5% of an all-time record high level.

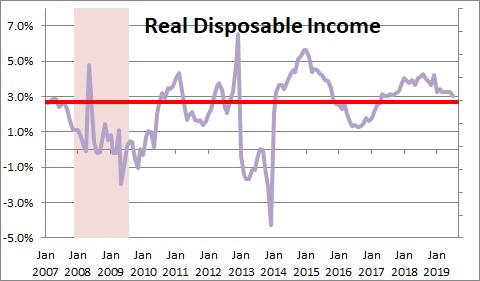

At the same time, real disposable income, which is what is left after taxes and inflation, is growing at a steamy 3.0% pace which is slightly faster than its long-term growth rate of 2.7%. The income gain is the result of a brisk pace of hiring combined with rapidly rising compensation. That combination is more than adequate for consumers to continue their current, relatively rapid, pace of spending.

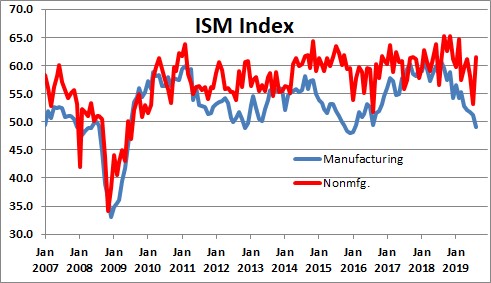

The dichotomy between the manufacturing sector of the economy and services is nowhere more evident than in the two purchasing manufacturers indexes – one for manufacturing, the other for services. The manufacturing index has been steadily declining for a year and actually contracted slightly in August, breaking a string of 35 consecutive months of growth. At its current level it is consistent with a 1.8% increase in GDP. By way of contrast, the non-manufacturing index remains at a lofty level which is consistent with GDP growth of 2.7%.

Keep in mind that the goods-producing sector of the economy (largely manufacturing, mining, and construction) is 17.7% of our economy. As noted earlier, the level of the ISM index for manufacturing is consistent with GDP growing at a 1.7% pace.

The service-producing sector (think retail and wholesale trade, finance, insurance, real estate, profession and business services, education, health care, entertainment, accommodation and food services) accounts for 70.2% of GDP. The ISM index for services is consistent with GDP growing at a 2.7% clip.

The remaining 12.1% is government spending which seems to be expanding at a 2.5% pace.

If you do the math, you should end up with GDP growth of about 2.5%.

The world is focused on trade and what that is doing to the relatively small, 17.7% goods-producing sector. It has clearly been hit by the tariffs. Fair enough. But this laser-like focus on trade is misleading because it completely ignores continued rapid growth in the far larger, 70.2% service sector of the economy. The pessimists are letting the tail wag the dog.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics’

Charleston, S.C.

Stephen… more brilliant math. Wish you were around to coach in my college econ classes back in the 60’s!