July 2, 2010

The Healing Continues

| January | July | |

| GDP | 2.5-3.0% | 3.25% |

| Unemployment Rate | 9.5% | 9.5% |

| Core CPI | 1.5-2.0% | 1.0% |

| Fed Funds Rate | 0-0.25% | 0-0.25% |

In January NumberNomics suggested that GDP growth for 2010 would be 2.5-3.0%. Growth in the first two quarters of the year were slightly faster than that, so at midyear we are inclined to boost that forecast a snitch to 3.25%. If that is the case, the unemployment rate should still end the year at about 9.5%. In January we talked about the core inflation rate (the CPI excluding the often volatile food and energy categories) averaging 1.5-2.0%. But inflation seems to be slower than expected, so we now anticipate core inflation this year of 1.0%. Against this background, we continue to expect no change in Fed policy not just through the end of this year but through the middle of 2011 as well. Let’s take these pieces in order.

Moderate GDP Growth

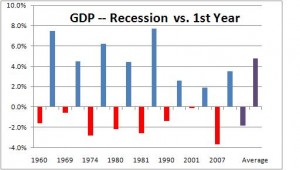

At the end of July we should learn that GDP grew at a 3.3% rate in the second quarter. If that forecast is accurate, it means that the economy has just completed its first year of expansion. While it may not feel much like it, the recession (presumably) ended a year ago in June 2009. During that period of time the economy expanded at a 3.5% pace. As shown below, in the first year of expansion growth typically averages about 5.0%, but given the sharp decline during the most recent recession one might have expected a snapback of 6.0-8.0% this time. That did not happen. By any historical standard the first year growth rate is anemic.

Why so slow? Two factors stand out.

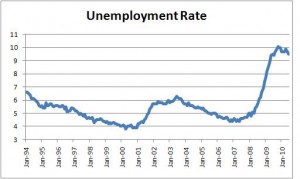

1. The economy did not produce jobs until January. Since then the private sector has been able to generate only about 90 thousand jobs per month. Worse, about a third of those jobs have been temps. Thus, the economy is still not producing the high paying, permanent jobs that are required. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate declined to 9.5% by midyear, but primarily because of declines in the labor force which are likely to be reversed later this year. Thus, we continue to expect the unemployment rate to be 9.5% at yearend.

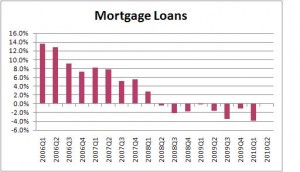

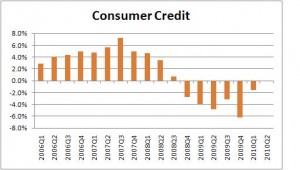

2. Consumers are far more interested in paying down debt than in adding to it. Consumer installment loans and mortgage loans have been declining steadily for the past two years. During the recession consumers experienced firsthand the consequences of too much debt, they got scared, and have been actively paying down debt since. For the economy to grow more rapidly, consumers and businesses must be willing to borrow again.

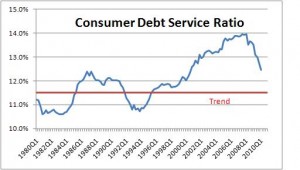

So how much longer might this slow-growth mode continue? Probably for at least another year. Shown below is the consumer’s debt service burden which measures principal and interest payments for all types of loans – including mortgages, car loans, and credit card debt – as a percent of income.

This ratio has been falling steadily for the past two years primarily because the consumer has been actively paying down debt, but also because interest rates have declined. Over the past 30 years or so this ratio has averaged about 11.5%, so we might think of that as a “comfortable” level of debt. At its current pace of decline, the consumer is unlikely to reach a “comfortable” debt level until the middle of 2011.

Looking into the crystal ball for the second half of the year we expect the following:

1. A continuation of sluggish consumer spending. The consumer is constrained by too much debt, a very high level of the unemployment rate, slow income growth given the modest pace of jobs creation, and some difficulty in attaining credit.

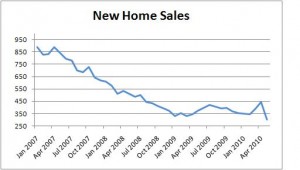

2. Housing will soften following the expiration of the tax credits. However, mortgage rates are at historically low levels of 4.5%, and property values have fallen by about 20% over the past couple of years, so do not expect housing to collapse.

On the positive side keep in mind that:

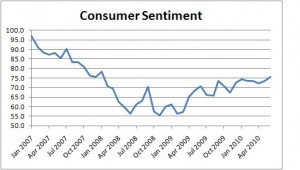

3. Jobs will probably climb faster in the second half of the year. Consumer confidence has, surprisingly, continued to inch upwards despite the decline in the stock market caused by the debt problems in Europe. That suggests that retail sales will continue to climb. Businesses are already working existing employees longer hours to satisfy demand and, at some point, will need to hire additional bodies. If all of that is true, then private sector employment, which averaged 90 thousand in the first five months of this year, should average 150-200 thousand in the second half.

4. Business spending has been driving the economy in the first year of expansion primarily because firms have spent money on technology and equipment designed to boost productivity and bolster earnings. In addition, strong growth from overseas – Asia in particular – has required them to step up the pace of production.

All of this probably translates into second half GDP growth of about 3.25%. While that is boring in some sense, the good news is that it will keep inflation low and keep the Fed out of the picture for some time to come.

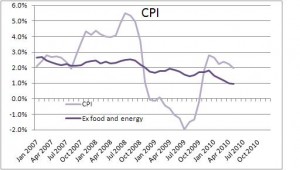

Further Inflation Slowdown

Inflation has been even more contained than anticipated during the first half of 2010. As the year-over-year increase in the CPI excluding the volatile food and energy categories has slipped to 0.9%. But for the past seven months this so-called “core” inflation rate has been essentially unchanged. So by yearend this core inflation rate may well be even lower.

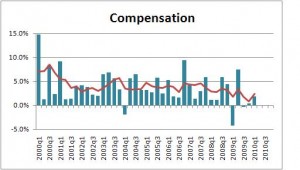

The primary reason for this reduced inflation outlook comes from the combination of growth in wages and productivity. It is important to remember that wages represent about two-thirds of a firms overall costs, so what happens to wages is an important factor in a firm’s decision about prices. As shown below, the nearly 10.0% unemployment rate has been putting downward pressure on wages, and will continue to do so for some time to come.

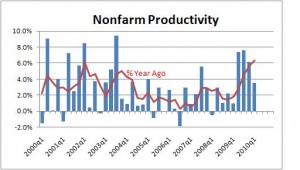

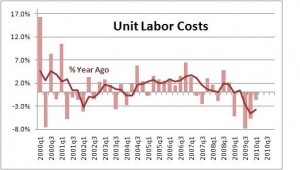

Over the past year compensation has risen just 2.3% (the red line) and is showing no sign of accelerating in more recent quarters. But that is just part of the story. What happens to productivity is equally important. Think of it this way. If a firm pays its employees 10% higher wages, one might think that would significantly increase costs and induce that company to raise prices. But suppose that those workers are 10% more productive and the firm is getting 10% more output from them. Then the cost per unit of output (or what economists call “unit labor costs”) has not changed at all, and there is no reason to contemplate higher prices. So what has been happening lately to productivity?

Productivity has been rising very rapidly. During the recession mass layoffs were common as firms tried to slash costs. During the past year, firms have spent considerable sums on technology and business equipment designed to make its workers more efficient. As a result, productivity has been rising at an extremely rapid 6.3% pace. So if compensation has been growing at 2.3% while productivity has been rising at a 6.3% race, then unit labor costs have been falling by about 4.0%. As long as unit labor costs continue to fall, there will be downward pressure on the inflation rate.

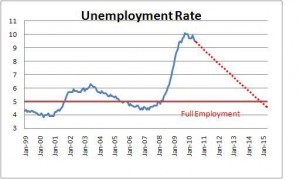

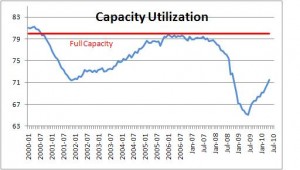

The Fed talks a lot about inflationary pressures being well-contained because of the “considerable slack” in the economy. Specifically, it is referring to the unemployment rate and the factory utilization rate. The unemployment rate currently is 9.5%. Economists would suggest that “full employment” would be about 5.0%. At that level everyone who wants a job has one. But, if the economy were to suddenly generate 250 thousand jobs a month continuously, it would take until 2015 to attain that level. Hence, there is considerable “slack” in the labor market which – as described above – it exerting downward pressure on inflation.

The Fed is also talking about the “slack” in the manufacturing sector. Currently capacity utilization rates in that sector are about 71%. Economists have found that when the utilization rates gets to about the 80% mark, there is a tendency for firms to boost prices. However, that situation is unlikely to occur until the end of next year.

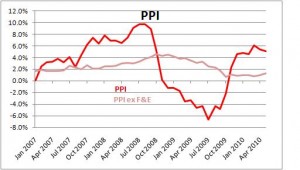

Is there a risk of deflation in the United States? Not really. Rapid growth in Asia has been putting upward pressure on commodity prices. The chart below indicates that producer prices have been rising at a 5.0% rate in the past year. And farther back in the pipeline, intermediate goods and crude goods prices have been climbing at annual rates of 10% and 20%, respectively. In the current environment it is difficult for wholesalers to push those higher commodity prices through to the consumer. Instead, the higher cost of materials is being absorbed by the wholesaler via reduced profit margins. Given these higher prices it unlikely that the U.S. will slip into Japanese style deflation.

Watching and Waiting

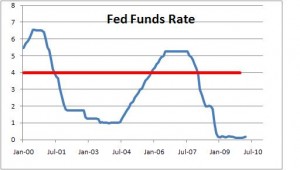

If you are in the Fed’s position you clearly continue to watch and evaluate. If the world develops roughly in line with what has been described earlier, there is no chance the Fed will change rates through the end of 2010 and probably through mid-2011 as well. Look for the funds rate to remain in its current range from 0-0.25% for the foreseeable future.

For the Fed to embark on a path towards higher rates several things have to happen:

1. The economy has to start growing consistently at a rate in excess of 4.5%.

2. If that happens, employment gains will climb to 250 thousand per month or so, and the unemployment rate will establish a clear downtrend. However, the Fed is unlikely to begin tightening until that rate dips below the 8.0% mark.

3. Unit labor costs need to start rising. As it stands, they continue to decline rapidly. Once wage gains begin to outpace the growth in productivity, the Fed might think about beglnning the process of moving towards a more “neutral” rate stance. Most economists would suggest “neutral” funds rate in today’s world would be 4.0% or a shade higher. So once the Fed starts boosting interest rates, it is going to be a process that continues gradually for probably two years. If the FOMC moves in 0.25% increments and they meet every six weeks, it will take that long just to get the funds rate back to a “neutral” level where it is no longer stimulating the economy.

While one might wish for faster growth going forward, the economy seems to be facing sufficiently rapid headwinds to make that difficult to achieve. But if inflation remains in check, and the Fed stays on the sidelines, the consumer can continue to pay down debt, job gains will gradually increase, and the healing process will continue.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, SC

Follow Me