December 8, 2017

It is impossible to overstate the importance of the corporate tax cuts that are on the verge of enactment. Over the next few years the corporate tax cuts should accomplish the following:

- Raise the economic speed limit from 1.8% to 2.8%.

- Boost growth in wages from 1.4% to 3.5%

- Accelerate growth in our standard of living.

- Boost the inflation rate slightly from 1.8% to 2.3%

- Keep the Fed on track to raise rates slowly to the 3.0% mark but no higher.

- Propel the stock market to a record high level.

- Extend the expansion to 2022 or beyond.

Back in the 1990’s the economy grew at a 3 .5% rate and, as a result, we all came to believe that in the good times the U.S. economy should grow at a similar pace. Since the current expansion began in June 2009 GDP growth has struggled to reach the 2.0% mark and economists endlessly point out how the current pace of expansion falls far short of growth registered at comparable periods of other business cycles. The often-cited culprits are the Republicans, or the Democrats, or Obama, or the gridlock in Congress, or the Federal Reserve. Or all the above. Because growth is so anemic, the naysayers note that it would not take much of a shock to push the economy into recession. They seem to live in constant fear that the next downturn is right around the corner. But the pessimists are wrong. The economy is alive and doing well, it is gathering momentum, and will continue to expand for many years to come. We are in the midst of the longest expansion on record.

To understand why growth has been so slow relative to other business cycles we need only to look at what economists call “potential GDP growth” which is essentially the economy’s speed limit. We cannot observe that particular number, but we can make a reasonable guesstimate by adding two numbers – the growth rate in the labor force and the growth rate in productivity. After all, if we know how many people are working and how efficient they are, we can probably make a reasonable estimate of how many goods and services they can produce – which is what GDP is trying to measure.

Back in the 1990’s labor force growth was 1.5%, productivity growth was 2.0%. Add them up and the economy’s speed limit 20 years ago was 3.5%. The economy grew that quickly for a decade. Not surprisingly, we have come to expect the economy to grow at a 3.5% pace in the good times which is why we are so frustrated by the 2.0% pace of the recent expansion.

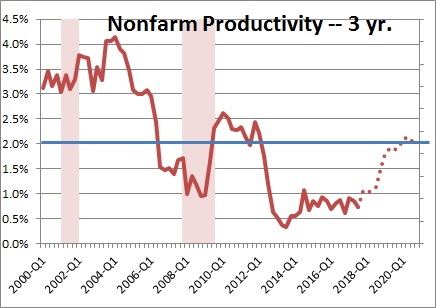

But the economy today simply cannot grow at a 3.5% pace. Labor force growth has slowed to 0.8%. Why? Because the baby boomers are retiring, and when they retire they leave the labor force. Baby boomers will continue to retire for another decade. Productivity growth has slowed to 1.0%. Why? Economists do not fully understand the reasons for this slowdown. Our favorite explanation is that the internet came into existence in 1995. In the early 2000’s the cloud and apps came along. These technological advancements completely revolutionized the way that we communicate with each other. As a result, productivity growth surged to 2.0%. But nothing quite so revolutionary has occurred in recent years and productivity growth has slipped to 1.0%. With labor force growth of 0.8% and productivity growth of 1.0%, the economic speed limit today is 1.8%. Thus, today’s economy can expand at only about one half of the pace it registered during the decade of the 1990’s. We are frustrated and disappointed. Surely, we can do better than that!

To boost our economic speed limit, we have two choices – achieve faster growth in the labor force, or find some way to boost growth in productivity. Because the baby boomers will continue to retire for another decade, we probably will not have much luck boosting growth in the labor force. If we are going to raise the economic speed limit we must stimulate growth in productivity.

Corporate tax cuts to the rescue!

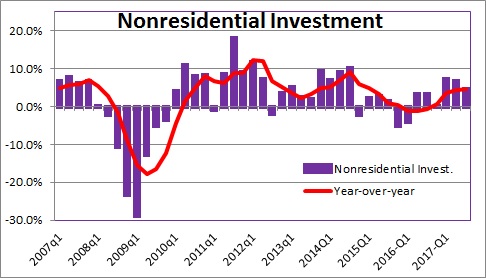

It is important to understand that productivity is closely tied to the pace of investment. Investment spending collapsed in 2014 and did not grow for two years. Part of the drop-off was tied to the collapse of oil prices. When oil prices plunged from $104 per barrel to $25, drillers could no longer operate profitably 75% of the wells that were in operation at that time and they shut them down. When they did that, they cut spending on oil drilling equipment and supplies. They curtailed spending on oil exploration and research. Investment spending in the oil sector was crushed. More broadly, business leaders were frustrated by the political gridlock in Washington. Why should they spend investment dollars when they have no idea what the economy might look like 1-, 2-, or 5-years down the road? Investment spending ceased to grow for more than two years. But oil prices are no longer at $25, they are at $57. Now those same drillers can profitably operate many of the previously-closed wells. Investment spending in the oil sector is on the rebound.

In November 2016 the American people elected Donald Trump as President. Trump ran on a platform of creating jobs and boosting investment spending. He pledged both individual and corporate tax cuts. He cut the corporate tax rate from 35% to 20%. He is going to allow companies to repatriate earnings at a favorable 5.25% tax rate rather than 35%. He is in the process of eliminating a wide range of confusing, overlapping, and unnecessary regulations. He was going to “Make America Great Again”. Within a month of the election many American companies announced that they were going to boost investment spending and create jobs. The laundry list included sizeable job announcements by industry leaders like Walmart, Amazon, Sprint, Pizza Hut, even the on-line Chinese retail giant Alibaba. Trump had not yet taken office!

Investment spending immediately began to rise. First quarter growth jumped by 7.2%. Second quarter was 6.7%. Third quarter climbed 4.7%. Fourth quarter growth is expected to be 5.5%. After failing to grow for two years, investment spending has surged in 2017 to 6.0%. Coincidence? We are not fans of President Trump, but the timing of the investment spending acceleration is hard to dismiss. Give credit where credit is due. We expect investment spending to continue to climb at a 6.0% pace in 2018.

CEO’s say that they do not plan to use the tax cuts to boost investment spending. Instead, they say they plan to increase shareholder dividends and buy back stock. Nonsense. The reality is that they have already begun to boost investment spending. Big time.

Despite their rhetoric, corporate leaders today act as if the soon-to-be-enacted corporate tax cuts are going to boost growth in productivity, accelerate GDP growth, keep inflation in check, prevent the Fed from raising rates too sharply, propel the stock market to still higher record levels, and lengthen the current expansion by another five years.

Consider productivity growth. In the past three years it has grown by 0.7%. As investment spending has surged in 2017 productivity growth in the past year has quickened to 1.5%. Coincidence? We do not think so. It is not hard to imagine that within a couple of years productivity growth might climb to the 2.0% mark. That is our bet.

Now let’s re-calculate the economic speed limit. Labor force growth of 0.8% combined with 2.0% growth in productivity raises the economy’s speed limit from 1.8% today to 2.8%. That may not match the 3.5% growth rate registered in the 1990’s, but it is vastly improved over recent years.

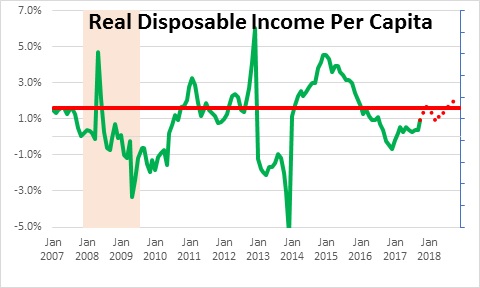

Faster growth in the economy allows our standard of living to grow more quickly. Economists typically measure standard of living growth by looking at real, after-tax, income per capita. Take our income, subtract what we pay in taxes, adjust for inflation, and see what is left. Today this measure of income is rising by 0.9%. But if the economy grows 1.0% more quickly, that number will jump to 1.9%, which is slightly faster than the 1.6% trend rate of growth over the past 25 years.

Faster growth in productivity will also help to alleviate upward pressure on inflation. At 4.1% the unemployment rate is below anybody’s estimate of the full-employment threshold. As a result, labor shortages are becoming more apparent. Wages are beginning to rise a bit more quickly. The fear is that higher wages will cause firms to start raising prices, which will cause inflation to accelerate. But perhaps less than you think because renewed growth in productivity can alleviate the impact of faster growth in wages. Think of it this way. If the firm you work for pays you 5.0% higher wages and you are no more productive, its wage costs have climbed by 5.0% and it might be tempted to raise prices to counter the higher labor costs. But what if it pays you 5.0% higher wages because you are 5.0% more productive? It does not care. It is getting 5.0% more output. Economists call wage pressures adjusted for productivity “unit labor costs”.

So, what is happening to “unit labor costs” currently? In the past year compensation has risen 1.4%, productivity has risen 1.5%. Thus, unit labor costs have declined 0.1%. No wonder the seemingly tight labor market has not yet put upward pressure on the inflation rate! The increase in wages has been countered by a commensurate increase in productivity.

But what about next year? Wage pressures in recent quarters have begun to quicken. We expect compensation in 2018 to rise 3.5%. We expect productivity to climb to 2.0%. Doing the subtraction implies that unit labor costs will rise 1.5%. That is a faster rate of increase in unit labor costs than we saw this year, so there should be a bit more upward pressure on the inflation rate. But the Fed has a 2.0% inflation target so an increase in ULC’s of 1.5% is perfectly consistent with its inflation objective.

Other things to consider when projecting the inflation rate for next year are the steady increase in recent months of commodity prices in general – not just oil. Also, the shortage of apartment units is causing rents to climb by almost 3.5% which is a big deal because housing represents about one-third of the entire CPI.

The bottom line is that we expect the core CPI (which excludes the very volatile food and energy components) to increase 2.3% in 2018 after having risen 1.8% this year. Last year was a little bit below the Fed’s 2.0% inflation target. Next year should be a bit above target, but not enough to alarm Fed officials.

Putting all this together, we expect GDP growth to pick up to 2.8% (its potential growth rate) during the next couple of years. Our standard of living will rise more quickly. Our paychecks will get somewhat fatter. Productivity will accelerate and thereby offset most of the increase in wages. As a result, inflation in the years ahead should continue at a 2.3% pace which is roughly in line with the Fed’s target.

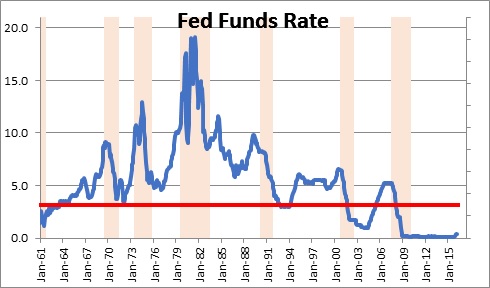

If that is the scenario that unfolds, the Fed should continue its gradual tightening until the funds rate reaches 3.0% by the middle of 2020. That 3.0% rate is what the Fed believes is a neutral” rate which means that it is neither providing economic stimulus nor trying to slow down the economy.

So, when might this expansion end? Historically the U.S. economy has never, ever, fallen into recession until the Fed has pushed the funds rate above that so-called neutral rate. At the end of the most recent expansion in December 2007, the funds rate reached the 5.0% mark.

When might the Fed raise the funds rate to 5.0%? We do not know! By mid-2020 the funds rate has achieved a neutral rate of 3.0%. If the economy is expanding at its potential pace of 2.8 it is not overheating. The inflation rate should be 2.3% which would be just a shade above its 2.0% target. Against that background, the Fed has no incentive to tighten further. It should boost the funds rate to the 3.0% mark — but no higher.

When will this expansion end? We do not know. Because the funds rate will not reach the so-called neutral rate of 3.0% until mid-2020 it should last at least that long. But in mid-2020 the Fed should have no reason to raise rates further. This means that a 5.0% funds rate is nowhere in sight. Could the expansion last until 2022? 2025? Absolutely. What we should be looking for are signs that the economy is overheating, and that inflation is moving substantially above the Fed’s 2.0% target. Those two pieces are nowhere in sight. The end of the expansion is likely to be least five years down the road.

This expansion is going in the history books as the longest expansion on record. The current record-holder is the decade of the 1990’s which lasted exactly ten years. The current expansion will reach that milestone in June 2019. We are suggesting 2022 or even 2025 as likely end dates. If the Federal Reserve can produce an expansion that lasts 13 years or longer, it certainly deserves high marks in our book.

All is well. Enjoy the coming year. Rock on!

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me