August 26, 2022

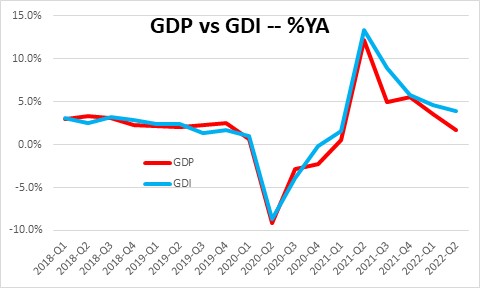

Economists continue to debate whether the economy is in recession. Citing back-to-back declines in first and second quarter GDP one group argues that the economy contracted in the first half of the year. Others look for confirming evidence from indicators such as employment, industrial production, and consumer spending which are supposed to decline sharply in a recession but did not. This latter group can also cite something called gross domestic income. Gross domestic product measures the value of the goods and services produced by the economy each quarter. Gross domestic income is the sum of income earned in the production of GDP. In theory the two measures should be identical. But they never are because they are constructed using different source data. In the first and second quarters of this year GDP declined at annual rates of 1.6% and 0.6%. GDI rose at annual rates of 1.8% and 1.4%. Given this difference some economists suggest that perhaps the best measure is an average of the two which would produce first quarter growth rate of 0.1% followed by 0.4% growth in the second quarter. So which is the most accurate barometer of what actually happened? We do not know and we never will. There is no truth in economics. That uncertainly also applies to the various measures of inflation. The one advantage that economists have is that they look at everything. Unfortunately, economists rarely agree. That means is you should listen to as many of them as you can and try to understand why they believe what they do. But in the end you have to reach your own conclusions. This is not easy. Nobody has a lock on truth when trying to analyze the economy.

Everybody is familiar with GDP. Gross domestic income comes out one month after the initial GDP release. Thus, we got our first look at GDI for the second quarter last Thursday. It rose 1.4%. GDP declined 0.6%. The same thing occurred in the first quarter – GDI rose 1.8%, GDP declined 1.6%. Given this discrepancy between these two indicators of economic activity, other economists suggest that it might be better to average the two. That would give us growth rates of 0.1% and 0.4% in the first two quarters. So which is it? Did the economy decline? Did it edge upwards? Or did it grow at a respectable pace? Nobody knows. To shed some light on this economists look at other indicators. In this case payroll employment, industrial production, and consumer spending. All typically fall sharply in a recession. But none did. Thus, most economists have concluded that the economy was not in recession in the first half of the year. The point is that we do not really know what happened to something as critical and basic as the pace of economic activity. Over the course of a year these indicators give essentially the same answer. But for any given quarter they can vary widely. This is a problem for economists, for you, and, most importantly, for our policy makers. If the Fed thought that the economy contracted in the first half of the year it should be cautious about further rate hikes. If it grew at a pace close to potential growth the Fed needs to push rates significantly higher to slow the economy and reduce inflation.

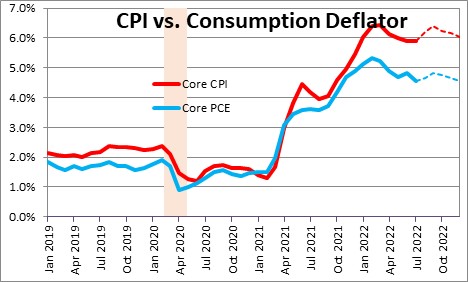

The same problem exists with the inflation rate. There are numerous measures of inflation. The CPI measures month-to-month price changes in a basket of 364 items that the consumer purchases each month. It includes the prices of some imported products. The GDP deflator examines prices of over 5,000 items. In addition to the prices of consumer goods and services it includes prices for capital goods, inventories, and housing. It is a much broader measure of inflation. But it is also a domestic measure of inflation. It does not include prices for any imported goods which can, at times, be important. The personal consumption expenditures deflator measures the prices in the GDP deflator that are purchased by people as opposed to businesses. Thus, it covers a wider array of goods and services than does the CPI. But it is a weighted measure of inflation which means that it also captures changes in consumer behavior. For example, if the price of beef rises shoppers may buy less beef and more of lower-priced chicken. Thus, the PCE deflator captures both price changes and changes in consumer spending happens. If that is not confusing enough, each measure can be calculated including or excluding the frequently volatile food and energy categories. So what is happening to the inflation rate it? It depends. All we can really say is that it seems to be rising at a rate somewhere between 4.5-8.5%,

Most people focus on the CPI. It is the most talked about inflation measure. But, rightly or wrongly, the Fed has chosen to focus on the personal consumption expenditures deflator excluding food and energy prices. It is this measure of inflation that it wants to grow at a 2.0% pace. If one compares the so-called “core” CPI to the “core” PCE deflator one finds that in the last year the core CPI has risen 5.9% which the PCE rose 4.6%. That is a huge difference. Historically, the CPI exceeds the PCE by only 0.2-0.3%. The current 1.3% divergence reflects the extent to which consumers are switching from expensive brand name products to generic goods and store brands. So which is the more accurate barometer of inflation? It depends but for all practical purposes the answer does not matter. The Fed is focusing on the core PCE so we should as well.

It is difficult to figure out both the “true” rate of growth in the economy and the “true” inflation rate. Everybody wants easy answers. But the real world is complicated. Economists can help because they follow all of these indicators. You do not have the time to do that. But even economists can have widely different views of both growth and inflation. So listen to as many economists as you can. Try to understand why they believe what they do. But then you must make your own decision as to which view most accurate depicts reality. It is your firm and your financial assets. You have to make the call.

Good luck!

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

“ There is no truth in economics”. Love that quote. Going to use.

2022 the year truth went from absolute to subjective!

Perhaps there has never been truth. We just didn’t know it. We used to believe everything. Now we believe nothing.